The number of outright failures of U.S. small businesses in the first months of the coronavirus pandemic was comparatively modest, but the months ahead look far grimmer as cash balances dwindle, federal help expires, and the disease surges back.

FILE PHOTO: A view of the Home Team Pub with strict social-distancing rules after reopening from coronavirus disease (COVID-19) restrictions in the Syracuse suburb of Liverpool, New York, U.S. July 22, 2020. REUTERS/Maranie Staab

That outlook, taking shape from a range of research in recent weeks by business organizations and think tanks, suggests a reckoning awaits Federal Reserve officials and other policymakers who rolled out support quickly in March and April, and by June seemed hopeful an economic rebound was taking root.

After the Fed’s June 10 meeting, Chair Jerome Powell said “assuming that the disease remains or becomes pretty much under control, I think what you see is...an expansion that builds momentum over time.” The 7-day moving average of daily deaths that day was showing a steady decline and the number of new coronavirus cases was under 20,000.

Both have turned higher, with daily new cases nearing 70,000. When the central bank meets next week it will have to recalibrate its outlook around a new wave of infections policymakers had initially excluded from their baseline view of a steady rebound in the second half of the year.

“The tone of next week’s ... the meeting is likely to be on the dour side,” said Karim Basta, chief economist at III Capital Management.

Recent surveys indicate programs rolled out in March, including the Paycheck Protection Program’s forgivable business loans, did prevent the worst in the pandemic’s first phase.

A recent survey covering more than 13,000 members of small business networking group Alignable found that among firms with at least one employee only an estimated 1.6% had closed permanently. That would translate nationally to about 96,000 of the roughly 6 million firms with between one and 500 workers.

The figure is consistent with estimates from Web site Yelp concluding around 77,000 firms listed on its review platform were shuttered for good.

Both are below an earlier study coordinated by the Harvard Business School putting more than 100,000 small firms at risk of failure in the initial weeks of the pandemic.

A study by the JP Morgan Institute using data through May showed cash balances among many of the smallest businesses, notably restaurants and personal service firms, skyrocketed in May as federal relief funds bought them time.

Sean Salas, chief executive of Camino Financial, an online lender focused on Latino-owned small businesses, said it was also borne out in a recent survey of loan recipients and applicants. Nearly 70% had reopened and almost all others were confident they would, as entrepreneurs pivoted to new business models, drew on family resources, or took other steps to stay afloat. So far.

As government funds were deployed early on, “I was very confident the failure rates would be low,” Salas said. “But as we think about the reemergence and the recovery, I do worry a bit more. The confidence level dipped at the end of June.”

ADJUST TO THE REALITY

Some measures of recovery and reopening have indeed stalled.

Several states have placed fresh restrictions on commerce likely to hit small businesses disproportionately - this time without offers of loans or expanded unemployment benefits for workers and consumers unless Congress acts.

After a spate of optimism in June, a National Federation of Independent Business monthly survey found 23% of respondents in early July said they’d be out of business within six months “under current economic conditions.”

Other recent surveys have found increasing numbers of small entrepreneurs expect the recession to outlast their resources.

“The small business sector stalled in late June, and with public funding running dry the situation could deteriorate more in the coming weeks,” said Oxford Economics analyst Gregory Daco. “The Fed will have to adjust their discourse to reality.”

While no updated economic projections are due at the Fed’s July 28-29 meeting, its policy statement and Powell’s press conference could describe the turn the economy seems to be approaching, with no clear sense that a robust reopening can proceed without risking faster coronavirus spread.

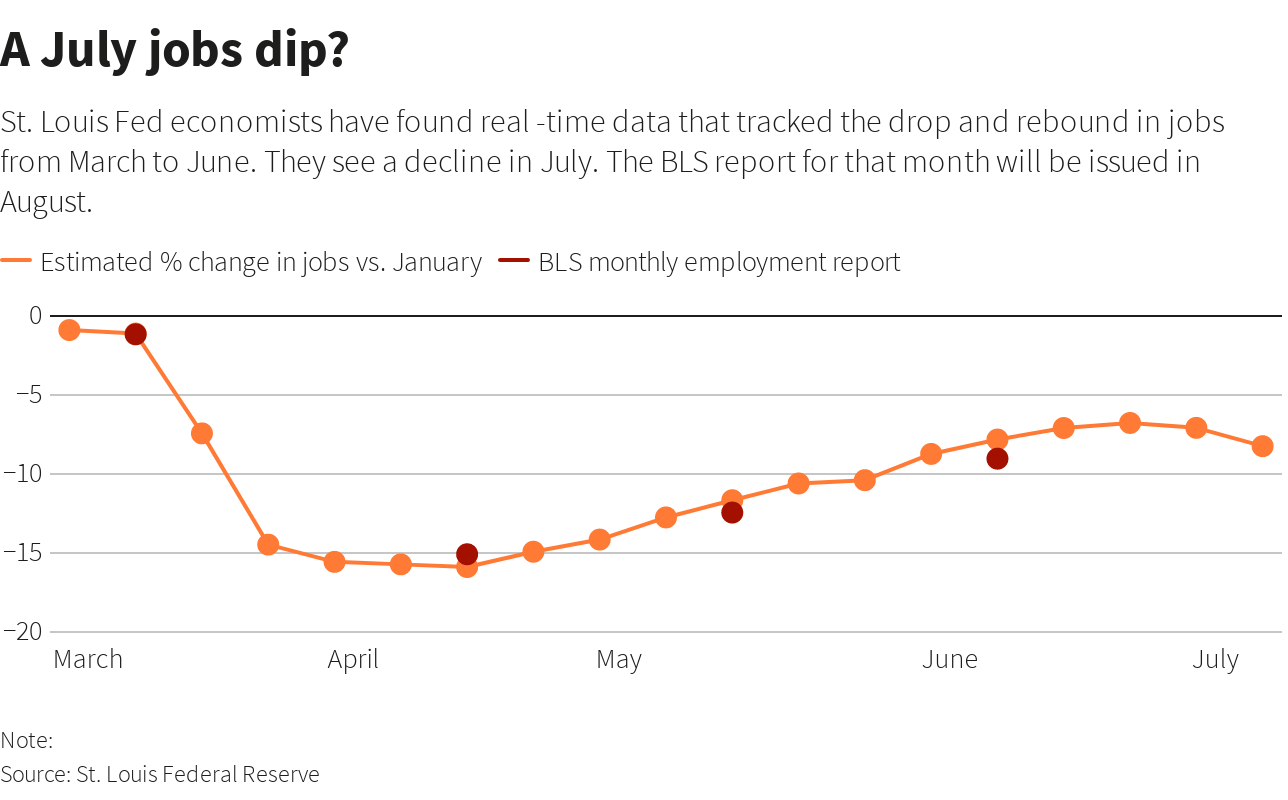

(Graphic: A July jobs dip? link: here)

May and June saw unexpected gains in employment as states lifted the virus-related restrictions that brought the economy to a halt in March and April.

Data released by Yelp this week showed the possible underside of that - a close correlation between user postings about bars and restaurants in May and the turn in infections that took root in June.

(Graphic: Yelp "interest" surged; virus followed Yelp "interest" surged; virus followed the link: here)

States that have been more successful in controlling the virus, like New York, also have higher percentages of businesses reporting as closed in surveys by groups like Alignable.

Bars are considered a particular hot spot for transmission, and states like Florida and Texas have reinstated restrictions on them. Overall, a Goldman Sachs “lockdown index” combining information on official restrictions and social distancing data, turned higher in early July after falling steadily from April’s peak.

(Graphic: The screws retighten? link: here)

“We do expect closures to continue,” said Yelp vice president for data science Justin Norman. “We anticipate states will roll back or delay reopening plans ... possibly turning even more temporary closures into permanent ones.”

Skilled nursing operators and associated providers received about $165 million in small loans under a federal program designed to keep businesses afloat during the pandemic, an analysis of public data by Skilled Nursing News has found.

In turn, those 3,300 loans — all under $150,000 apiece — helped operators in the space preserve a total of 35,210 jobs across the 50 states, Puerto Rico, and Guam, according to federal data analyzed by SNN.

For comparison, more than 15,000 agencies involved in the home health care space pulled down around $666 million in total relief through those $150,000-and-under loans, a separate analysis for our sister website Home Health Care News determined.

The federal Payroll Protection Program, part of the larger $2 trillion CARES Act coronavirus stimulus package passed in March, made hundreds of billions in potentially forgivable loans available to firms of all types through the Small Business Administration.

Under the terms of the program, businesses could receive up to $10 million in emergency financing from private lenders backed by the SBA. Any portion of that money put toward essential expenses — primarily payroll, but also costs such as mortgage interest, rent, and utilities — can be fully forgiven, with a 4% interest rate and 10-year repayment term on proceeds spent for any other purpose.

The forgiveness could also be jeopardized if employers lay off workers after receiving the funds, as the retention of workers during the initial COVID-19 economic downturn in March was a major rationale for the program.

“It’s a loan that’s designed to allow people to retain their workforce, and then assist with some of the operational expenses during the crisis time,” Adam Sherman, head of senior care lending at major SBA player Live Oak Bank, told SNN in March. “The big hook, the big carrot on this particular program is that the loan is 100% forgivable if the business spends the money on the right things.”

The SBA and the Department of the Treasury have indicated that companies receiving under $2 million in PPP loans will automatically be assumed to have acted in good faith with their applications, and will not be targeted for audits under a “safe harbor” strategy, citing the necessity of sending funds quickly as well as the limited capacity for investigations.

“SBA has determined that this safe harbor is appropriate because borrowers with loans below this threshold are generally less likely to have had access to adequate sources of liquidity in the current economic environment than borrowers that obtained larger loans,” according to a Treasury FAQ on the program. “This safe harbor will also promote economic certainty as PPP borrowers with more limited resources endeavor to retain and rehire employees.”

That said, back in March, Sherman recommended that all borrowers maintain detailed records of how they spend their PPP dollars to ensure full compliance.

SNN used the North American Industry Classification System (NAICS) identification codes — 6231 and 632110 — for “nursing care (skilled nursing facilities)” to identify the businesses in the space that received PPP loans of under $150,000.

In addition to traditional nursing home operators, the classification also includes convalescent homes and hospitals, assisted living facilities that provide nursing care, rest homes with a nursing component, and inpatient care hospices, according to NAICS.

Loans by state

Unsurprisingly, the states with the greatest populations led the way in total financing sent to skilled nursing providers: Operators in California accessed a total of $25.7 million of small-dollar PPP loans, well ahead of second-place Texas with $12.4 million in SBA backing. Florida came in third with a little over $10 million, followed by Illinois ($7.5 million) and North Carolina ($6.9 million) to round out the top five; explore the interactive map below to see how your state fared.

Nationwide, the loans averaged a little under $50,000 apiece, saving an average of about 11 jobs per company.

The figures presented here represent just a fraction of the $525 billion in total loans issued under the program through the end of June; interested businesses also have until August 8 to apply for funds through an extended deadline.

PPP also served as only one avenue of relief for nursing homes, with the federal government releasing billions in CARES Act aid to all health care providers based on prior Medicare and Medicaid reimbursements — as well as a specific tranche of $4.9 billion dedicated exclusively to skilled nursing facilities, and another $5 billion for SNFs released this week.