John Wilkins, 39, lost his job as a facilities director at a fast-food restaurant in Santa Barbara, California, in March when the coronavirus outbreak began. With the $600 weekly unemployment benefit from Washington, he was making up his previous income and managed to save enough of a cushion to cover an extra month's rent.

But then the benefit expired, and a $300 temporary replacement is soon to expire, as well. He has had no luck finding a job and has little idea of what comes next.

"After this month, I don't know what we're going to do," Wilkins said. "We canceled cable. We got rid of our crappy air conditioner. We've cut way back. Still not making it."

For months, it was a lifeline: a check for $600 a week, allowing people put out of work by the coronavirus pandemic to pay rent, buy food and build some savings to ride out the storm.

But with that benefit now gone and a patchwork of replacement aid nearing its end, tens of millions of Americans are dealing with uncertain futures, unsure of their income beyond even the next month or whether they can find jobs to replace it. Nor can they take the roofs over their head for granted: While emergency measures protect them from eviction for now, without additional aid they could lose their housing as soon as the order expires at the end of the year.

The $600 benefit, a provision of the CARES Act, which passed in March with near-unanimous support in Congress and was signed into law by President Donald Trump, expired at the end of July.

The House passed a bill in May, the HEROES Act, that would extend the weekly benefits through January. The White House and Senate Republicans have called for a lower benefit, arguing that $600 was too high — for most recipients, it's more than their pre-pandemic income — and would discourage work.

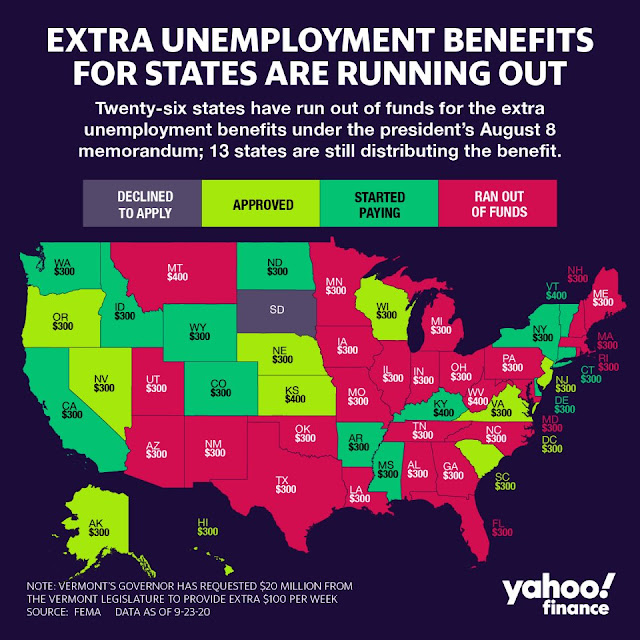

Close to two months later, talks over further assistance have collapsed. Trump took executive action to provide some temporary relief, offering states $44 billion through the Federal Emergency Management Agency to finance a temporary $300 weekly benefit on top of their unemployment insurance.

But the benefit lasts only up to six weeks before the money runs out. Because states applied for the benefits retroactively to the end of July, some recipients have already gotten their final payments. That leaves them with only state unemployment, which varies widely and averaged just over $300 per week in July, according to federal data.

The Bureau of Labor Statistics says nearly 30 million people are still receiving some type of unemployment benefit, but the true number is likely to be lower.

With hopes for a deal in Congress fading, the Trump administration has also implemented a sweeping moratorium on evictions on public health grounds under the authority of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention for individuals making under $99,000 or couples making $198,000. That also filled a gap left by the expiration of protections under the CARES Act.

Unemployment aid program threatened by fraud

SEPT. 18, 202001:56But those moves only delay evictions, and they don't offer direct financial aid, leaving both tenants and landlords on the hook for now and without a picture of what happens if the moratorium ends and tenants accrue months of unpaid rent.

The ban on evictions was a boon for Jennifer Tobin of Corona, California, whose work for a sports league was put on hold because of the pandemic.

But the lease on her apartment is up in October, and she is struggling with how to proceed. Staying there on a month-to-month lease would preserve her flexibility but cost more while signing a long-term lease would lock her and her son into a place she can't afford without a job and with the extra unemployment assistance now gone.

"Rent is crazy expensive, and who else will take someone in who doesn't have an income?" Tobin said. "I've been talking to my apartment community, and they say they don't want me to leave, but at the same time I can't pay rent, and it puts me in debt. So I don't know what to do."

Fortunately for Tobin, her luck recently turned: Her employer finally recalled her in mid-September, with a 10 percent pay cut, just as the FEMA payments were ending.

But not everyone will be so lucky. While some of the worst effects of the sudden loss of aid may be delayed, many unemployed and struggling Americans are trapped in a kind of limbo, with benefits that could run out as soon as this month and protections that could keep them in their homes for now but leave them with rising debt that would only force them out later.

An analysis by Mark Zandi, chief economist at Moody's Analytics, estimated that Americans owe over $25 billion in back rent, which could balloon to $70 billion by the end of the year.

Diane Yentel, president and CEO of the National Low Income Housing Coalition, said, "Landlords are going to evict if renters aren't paying the rent at some point."

Along with the $3.5 trillion HEROES Act, which would include aid for housing, the House passed a $100 billion bill in June to provide rental assistance, which housing advocates have argued is necessary to help make up the gap.

Senate Republicans voted on their own $500 billion relief bill this month, which would have extended $300 weekly benefits through December but didn't include new housing aid. Democrats blocked the bill while calling for a larger aid package. The White House has said money authorized by previous relief bills could potentially be used for rental assistance, but housing advocates warn that the funding is likely to fall short.

Joel Griffith, a research fellow at the conservative Heritage Foundation, said an eviction moratorium without some additional relief — from the federal, state, or local governments — could have negative downstream effects throughout the economy, putting small landlords in difficult financial straits, as well as their tenants. He recommended keeping benefits narrowly targeted to unemployed tenants.

"We're not talking about enormous corporate conglomerates. Often the landlords are people who bought several rental properties and are relying on it as a source of income or even retirement income," he said.

Many of those strains could be resolved if those who are in need of additional aid could find jobs. But while millions of people have returned to work after the worst of the slowdown last spring, many industries are still lagging.

"I'm looking in the restaurant industry, but unfortunately right now it's hurting pretty bad," said Loryn Cadwallader, who was furloughed from her management job at a chain restaurant in Sanford, Florida.

She hopes to return soon as locations begin to reopen, but she has a little backup if she can't. Her state approved only four total weeks of stopgap benefits, which Cadwallader said she's already received.

Overall, jobs in hospitality and leisure, which includes bars, restaurants, hotels, and theaters, are still 25 percent below their pre-pandemic levels. In many places, sports arenas still don't have audiences, live music venues are still shuttered, and indoor eating and drinking establishments are still under tight restrictions.

Virginia Davis, whose job catering banquets at a downtown Minneapolis hotel is on hold, said she has taken on part-time work at a liquor store, even though the wages count against her unemployment benefits and add little to her income as a result.

"It's literally to get myself out of the house," she said. "It's hard to focus on anything else in your life other than the fact you're not working."

As of July, there was an average of 2.5 unemployed persons for every job opening, according to federal data. That's down from April, but in the pre-pandemic economy, the job openings outnumbered the jobless.

"We're in a situation where millions of people have been thrown out of work, and for those looking for a job, there are far fewer opportunities," said Nick Bunker, director of economic research for North America at Indeed Hiring Lab.

Some advocates for more relief are worried that momentum to help the jobless could wane as large companies and more affluent Americans bounce back and leave more marginalized groups behind.

"I feel like the attitude toward unemployment insurance is like the attitude toward the virus itself at this point," said Michelle Evermore, a senior policy analyst at the National Employment Law Project, a liberal group. "There are so many people tired of things being bad that they're pretending they just aren't bad anymore."

For Davis, the picture at her hotel isn't brightening. Last week, managers permanently let go of over 120 workers, citing a "catastrophic loss of business." Initially, Davis thought she was among them, but she said she found out later that she had erroneously been included on a call announcing the layoffs.

"As for the $300," she said, "that ends this week."