Young people have been particularly hard hit by the pandemic's disruption to the jobs market.

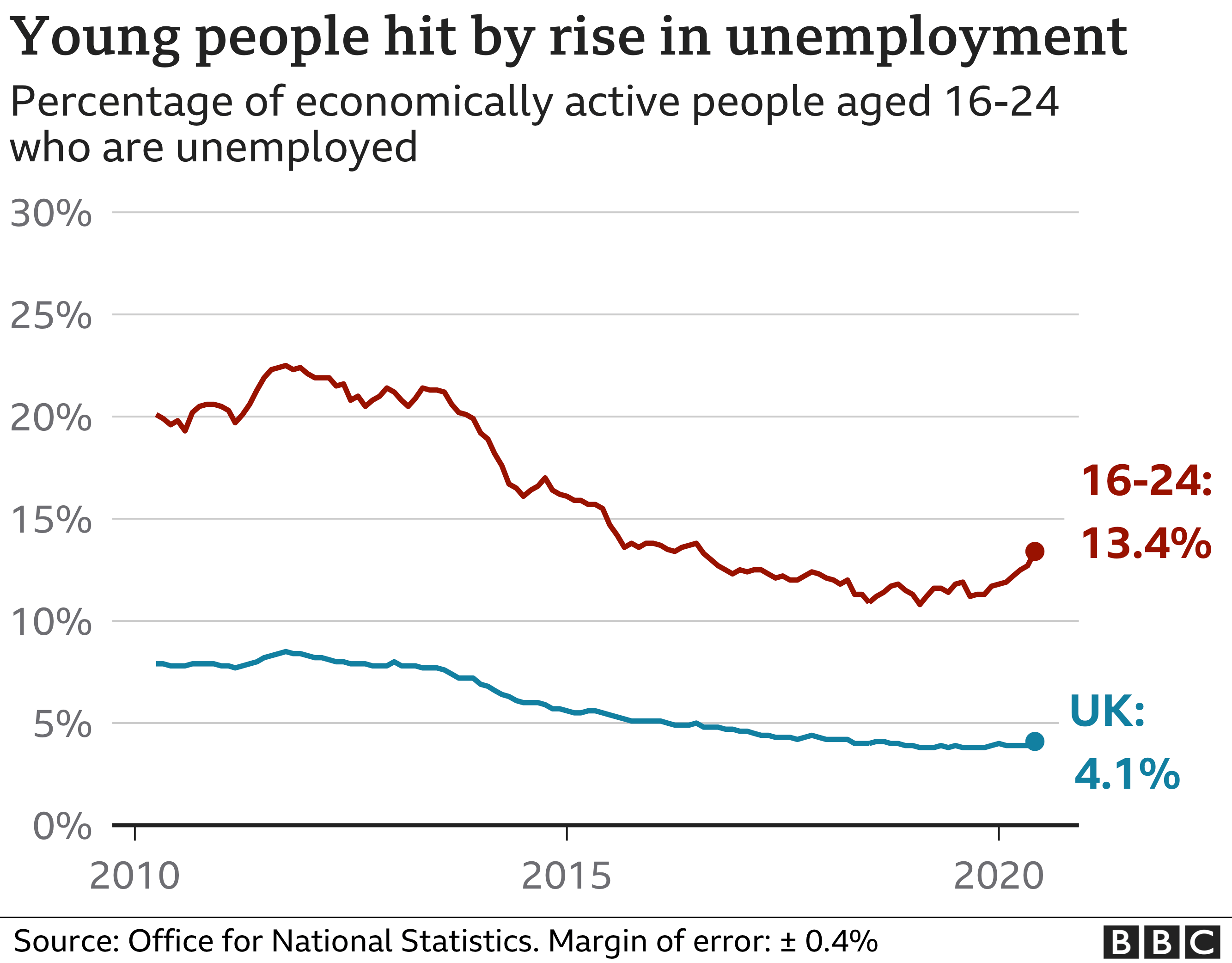

The under-25s saw the biggest rise in unemployment during the lockdown, and some graduate or entry-level roles attracted thousands of more applications than usual.

1. Young people left the workplace first

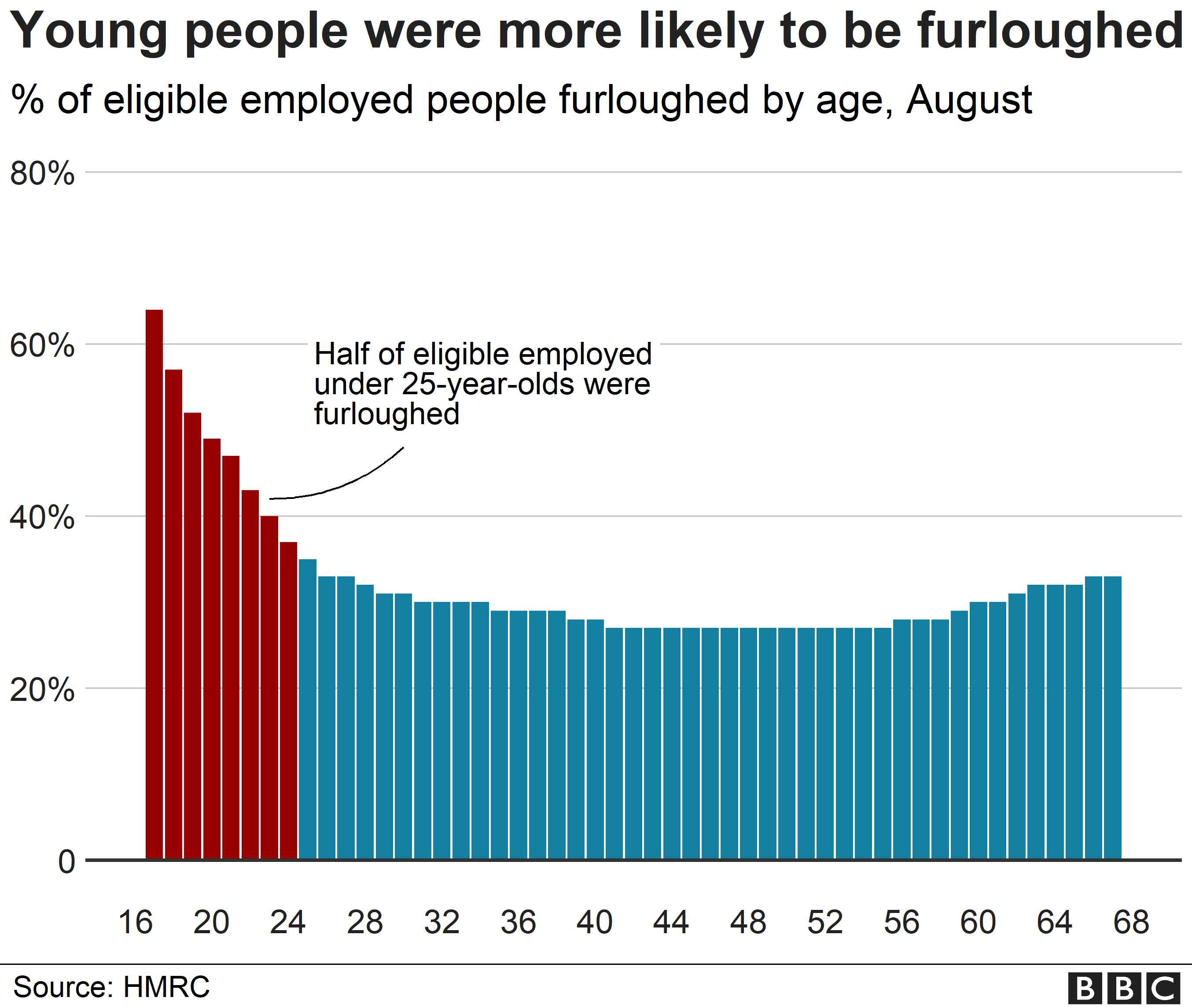

Under-25s were more likely to be furloughed than any other age group.

In the first three months of lockdown, half of eligible 16 to 24-year-olds were placed on the scheme, which supports people unable to work because of the pandemic, compared with one in four 45-year-olds.

Hannah Slaughter, an economist at the Resolution Foundation think tank, says hard-hit sectors like retail and hospitality - where many jobs cannot be done from home - have a disproportionately young workforce.

They were also the age group also most likely to lose their job, with the youth unemployment rate rising to 13.1%, compared with 4.1% for the whole UK.

About 7% of 18-24 year-olds reported they had been made redundant because of the pandemic, compared with 4% of 50-65 year-olds.

The government hopes to address this with its Kickstart scheme, which will pay employers £1,500 for every 16 to 24-year-old to whom they offer a ''high quality'' work placement.

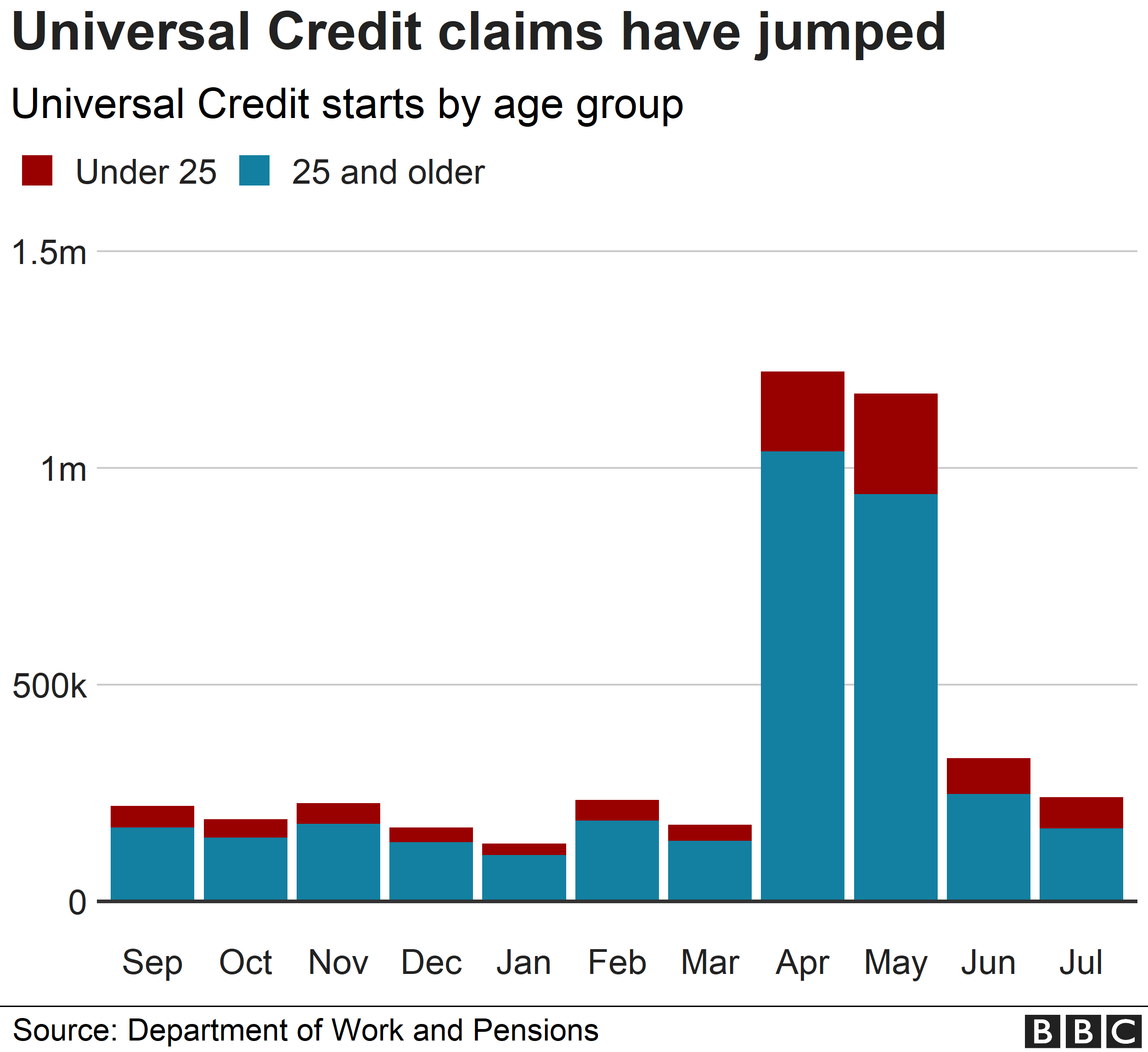

2. Under-25s now make up a third of new universal credit claims

As youth unemployment rose, so too did the number of young people claiming universal credit.

By July, just under one in three first-time universal credit claimants was under 25, up from one in five in March.

But Ms Slaughter expects youth unemployment to get worse when the furlough scheme ends in October.

''Young people are more likely to be in sectors which still aren't up to the levels of activity before the pandemic" she said.

''When businesses start making difficult decisions about redundancies, young people are likely to be disproportionately affected.''

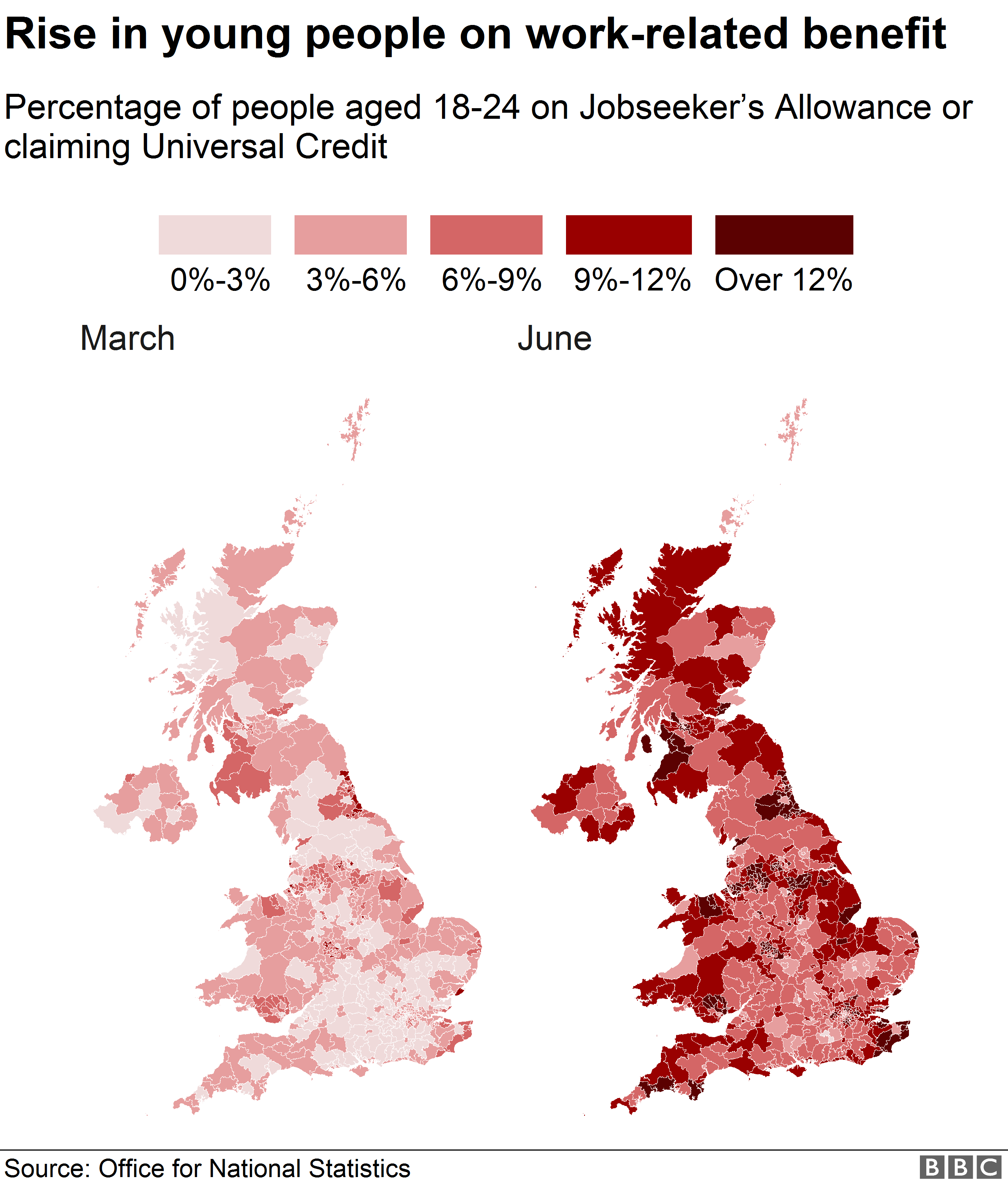

3. Young adults in northern England were worst affected

These changes have not been evenly felt across the country, with more deprived areas seeing a quicker uptake in work-related benefits by young people.

Using data on the uptake of universal credit and jobseeker's allowance, BBC analysis found that the proportion of young people on the benefits had doubled between March and June.

The worst-hit areas were generally in the north of England, with parts of Liverpool and Blackpool most affected.

In Liverpool's Walton area, for example, one in five 16-24-year-olds is now claiming universal credit or jobseeker's allowance - up from 7% in January 2020.

In total, 50 constituencies across the UK now have more than 15% of young adults claiming one of the benefits.

4. Online graduate job vacancies fell by 60%

Those looking for a job fresh from university are facing a tough time

The number of graduate jobs advertised fell 60.3% in the first half of 2020 on one online recruitment website, compared with a 35.5% overall fall in adverts.

About 5,000 jobs were listed on the CV-Library platform in January-July in the ''graduate'' jobs category, compared with 2,000 a year earlier.

Within that, graduate jobs advertised in marketing fell by 84%, while roles in construction and administration both dropped by more than 70%.

Applications only fell by 33%, meaning considerable extra competition for many roles. Twice as many people applied for public sector roles than the year before, and five times as many for IT vacancies.

One positive was the average graduate salary on the platform increased by 7.1% year-on-year to £24,626.

The fall in vacancies is borne out across the UK. Positions on the online platform Adzuna were 45% lower in mid-September than in 2019, according to Office for National Statistics analysis.

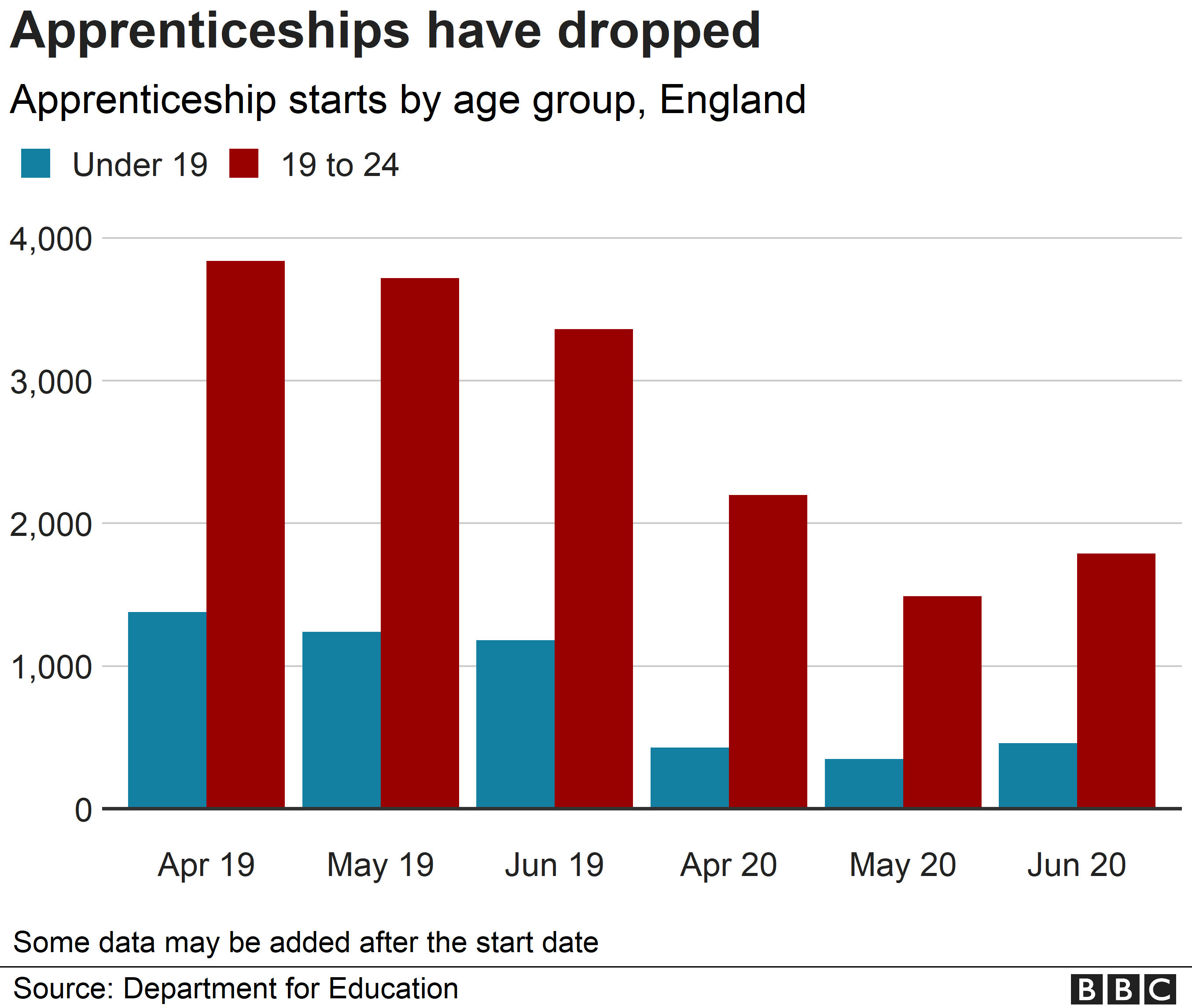

5. Apprenticeships have stalled

Companies have taken on fewer apprenticeships over lockdown.

From 23 March to 30 June, apprenticeship starts halved compared with the previous year, but this fall was not evenly split between age groups.

Unsurprisingly, the sectors which saw the sharpest drop across all age groups were retail and tourism, which both declined by 75%. However, education placements only declined by a quarter.

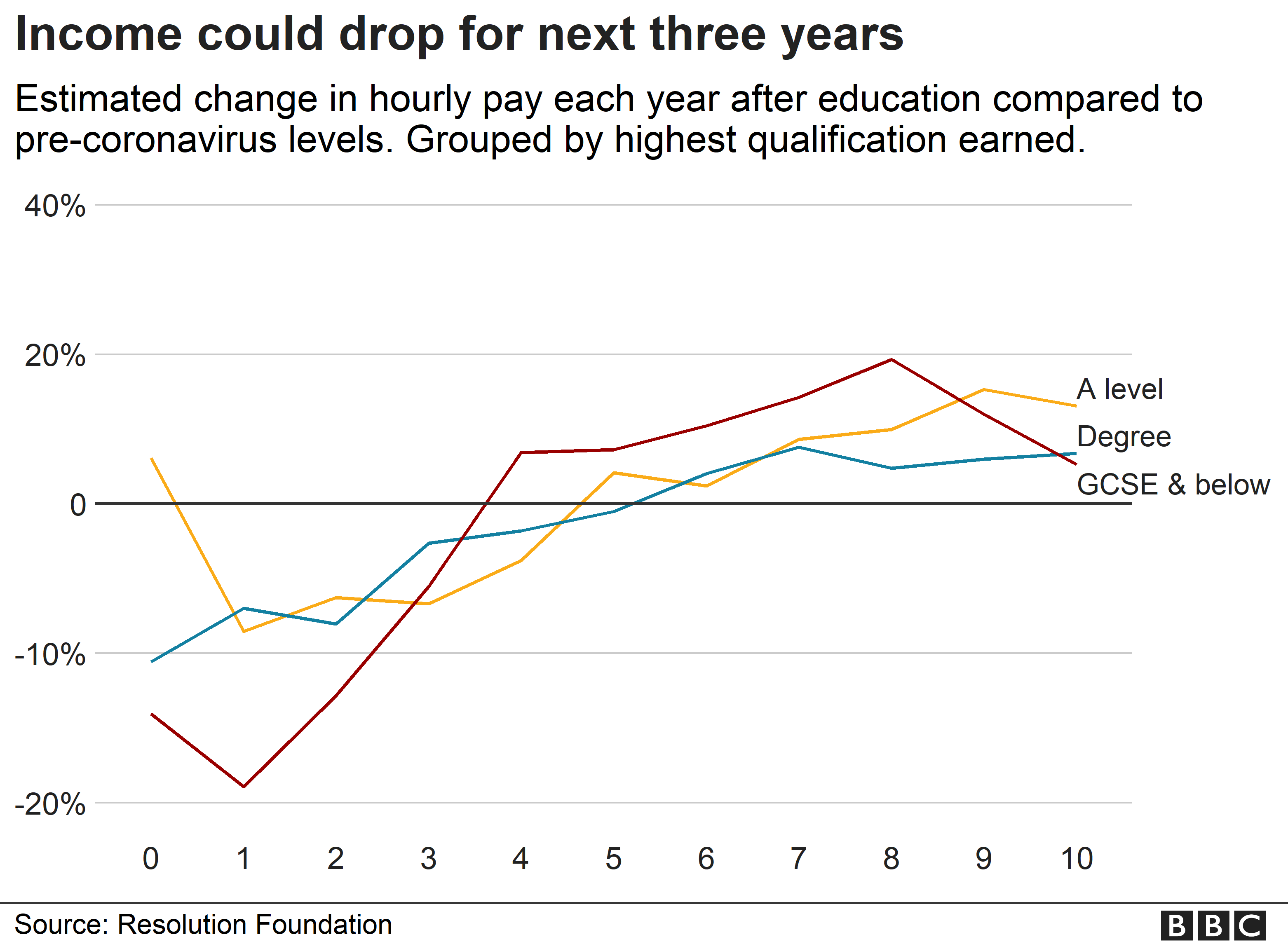

6. Young people's pay could be lower for three years after the pandemic

The UK's financial watchdog, the Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR) estimates unemployment will hit 10% by the end of 2020, up from 4.1% last year.

If this happens, young people who do find employment will face lower average wages for several years, Resolution Foundation analysis suggests, as they ''trade down'' to the best job available.

Two years after leaving full-time education, it expects new education leavers' hourly pay, after inflation, compared with pre-pandemic times, to be:

- 8% lower for highly qualified leavers (degree and above)

- 6% lower for mid-qualified leavers (A-level or equivalent)

- 13% lower for lower-qualified leavers (GCSE and below)

As happened after the 2008 recession, lower-skilled workers are likely to take the biggest hit. But the effect will last longer for mid and high-skilled workers, who may end up in sectors with less opportunity for a pay rise than offered by traditional graduate jobs.

That assumes lower-skilled workers can actually get a job. The think tank predicts they are a third less likely to be in employment three years after entering the jobs market, than if the pandemic had never happened.

7. Young people are more likely to stay in education

One positive outcome of the crisis is that younger people may remain in education. This would shield them from the worst of the downturn, and lead to higher productivity and a better-skilled workforce.

![Young people are keen to stay on in education. [ 40.5% of 18 year-olds applied to university by June, a record high ],[ 17% spike in new applications between March and June ],[ 1 year extra study could halve a low-skilled worker's unemployment chances ],[ 10% rise in postgraduate applications in the 2008-9 recession ], Source: Source: UCAS, Resolution Foundation, Image: Woman in library](https://ichef.bbci.co.uk/news/1632/idt2/idt2/a85b2cd3-45a5-4a79-889e-b83c4a5fbc5f/image/816)

To an extent, this happened in the 2008 recession. The effect may be much larger this time around, says Xiaowei Xu of the Institute for Fiscal Studies, as sectors like hospitality and retail are also where many people first start working.

''There's an incentive to staying on in education because of how terrible the economy is, which means that people may receive more and better education."

She adds that this year's A-Level grade inflation means some students will go to a better university than they would have done.