Higher mortgage rates have sent home sales tumbling. Credit card rates have grown more burdensome, and so have auto loans. Savers are finally receiving yields that are actually visible, while crypto assets are reeling.

The Federal Reserve’s move Wednesday to further tighten credit raised its benchmark interest rate by a sizable 0.75 percentage point for a second straight time. The Fed’s latest hike, its fourth since March, will further magnify borrowing costs for homes, cars, and credit cards, though many borrowers may not feel the impact immediately.

The central bank is aggressively raising borrowing costs to try to slow spending, cool the economy, and defeat the worst outbreak of inflation in two generations.

The Fed’s actions have ended, for now, an era of ultra-low rates that arose from the 2008-2009 Great Recession to help rescue the economy — and then re-emerged during the brutal pandemic recession, when the Fed slashed its benchmark rate back to near zero.

Chair Jerome Powell hopes that by making borrowing more expensive, the Fed will succeed in slowing demand for homes, cars, and other goods and services. Reduced spending could then help bring inflation, most recently measured at a four-decade high of 9.1%, back to the Fed’s 2% target.

Yet the risks are high. A series of higher rates could tip the U.S. economy into recession. That would mean higher unemployment, rising layoffs, and further downward pressure on stock prices.

How will it all affect your finances? Here are some of the most common questions being asked about the impact of the rate hike:

___

I’M CONSIDERING BUYING A HOUSE. WHAT’S HAPPENING WITH MORTGAGE RATES?

Higher interest rates have torpedoed the housing market. Rates on home loans have nearly doubled from a year ago to 5.5%, though they’ve leveled off in recent weeks even as the Fed has signaled that more credit tightening is likely.

That’s because mortgage rates don’t necessarily move in tandem with the Fed’s increases. Sometimes, they even move in the opposite direction. Long-term mortgages tend to track the yield on the 10-year Treasury note, which, in turn, is influenced by a variety of factors. These factors include investors’ expectations for future inflation and global demand for U.S. Treasurys.

Investors expect a recession to hit the U.S. economy later this year or early next year. This would force the Fed to eventually cut its benchmark rate in response. The expectation that the Fed will have to reverse some of its hikes next year has helped reduce the 10-year yield, from 3.5% in mid-June to roughly 2.8%.

WILL IT BE EASIER TO FIND A HOUSE?

Sales of existing homes have dropped for five straight months, while new home sales plunged in June. If you’re financially able to go ahead with a home purchase, you’re likely to have more choices than you did a few months ago.

In many cities, the options are few. But the number of available houses nationwide has started to rise after falling to rock-bottom levels at the end of last year. There are now 1.26 million homes for sale, according to the National Association of Realtors, up 2.4% from a year ago.

I NEED A NEW CAR. SHOULD I BUY ONE NOW?

The Fed’s rate hikes typically make auto loans more expensive. But other factors also affect these rates, including competition among car makers, which can sometimes lower borrowing costs.

Wednesday’s rate hike won’t likely affect new-vehicle sales much because those buyers are mainly affluent customers who won’t be squeezed by a relatively small uptick in monthly payments, said Jonathan Smoke, chief economist for Cox Automotive. By contrast, he said, used-car buyers with weaker credit who pay higher loan rates could be hurt.

“Many used-vehicle buyers are already acutely feeling the impacts of higher prices for energy, food, and rent,” Smoke said.

Used vehicle prices have begun to fall, he noted, and vehicle availability is beginning to return to normal levels.

The full amount of a Fed rate hike doesn’t always pass through to auto loans, according to Bankrate.com. New 60-month loans for new vehicles have risen about a percentage point this year to an average of 4.86%, Bankrate.com says, while a 48-month used-vehicle rate rose just under 1 point to 5.38%.

WHAT WILL HAPPEN TO MY CREDIT CARD?

For users of credit cards, home equity lines of credit, and other variable-interest debt, rates would rise by roughly the same amount as the Fed hike, usually within one or two billing cycles. That’s because those rates are based in part on banks’ prime rate, which moves in tandem with the Fed.

Those who don’t qualify for low-rate credit cards might be stuck paying higher interest on their balances. The rates on their cards would rise as the prime rate does.

The Fed’s rate increases have already sent credit card borrowing rates above 20% for the first time in at least four years, according to LendingTree, which has tracked the data since 2018.

HOW WILL THIS AFFECT MY SAVINGS?

You can now earn more on bonds, CDs, and other fixed-income investments. And it depends on where your savings if you have any, are parked.

Savings, certificates of deposit, and money market accounts don’t typically track the Fed’s changes. Instead, banks tend to capitalize on a higher-rate environment to try to boost their profits. They do so by imposing higher rates on borrowers, without necessarily offering any juicer rates to savers.

But online banks and others with high-yield savings accounts are often an exception. These accounts are known for aggressively competing for depositors. The only catch is that they typically require significant deposits.

HOW HAVE THE RATE HIKES INFLUENCED CRYPTO?

Like many highly valued technology stocks, cryptocurrencies like bitcoin have sunk in value since the Fed began raising rates. Bitcoin has plunged from a peak at about $68,000 to $21,000.

Higher rates mean that safe assets like bonds and Treasuries become more attractive to investors because their yields are now higher. That, in turn, makes risky assets like technology stocks and cryptocurrencies less attractive.

All that said, bitcoin is suffering from its own problems that are separate from economic policy. Two major crypto firms have failed. The shaken confidence of crypto investors is not being helped by the fact that the safest place you can park money now — bonds — seems like a safer move.

WILL MY STUDENT LOAN PAYMENT GO UP?

Right now, payments on federal student loans are suspended until Aug. 31 as part of an emergency measure that was put in place early in the pandemic. Inflation means that loan-holders have less disposable income to make payments. Still, a slowed economy that reduces inflation could bring some relief by fall.

Depending on the state of the economy, the government may choose at the end of summer to extend the emergency measure that’s deferring the loan payments. President Joe Biden is also considering some form of loan forgiveness. Borrowers who take out new private student loans should prepare to pay more. Rates vary by lender but are expected to increase.

Ah, the bacon, egg, and cheese. The classic bodega breakfast sandwich is a staple in many a New Yorker’s diets. It’s easy to make, easy to eat on the go, and cheap — although not as cheap as it used to be.

To keep up with today’s levels of inflation due to the pandemic and Russia’s war with Ukraine, bodega owners are faced with no choice but to raise the prices of their famously low-priced breakfast sandwiches.

“Bacon, egg, and cheese -- you can’t take that sandwich away,” said Francisco Marte, who owns a bodega in the Bronx. “That’s the favorite sandwich for the New Yorkers.”

Marte has had to increase prices on everything from sugar to potato chips -- and the cost of his bacon, egg, and cheese sandwich is up from $2.50 to $4.50.

At the wholesale level, inflation climbed 11.3% in June compared with a year earlier, the U.S. Department of Labor reported. Producer prices have surged nearly 18% for goods and nearly 8% for services compared with June 2021.

“These things happen. And normally, in normal times, the supply chain is able to absorb some of that shock,” said Katie Denis, a spokesperson with the Consumer Brands Association, a trade group representing food, personal care, and cleaning companies. “Right now, there’s just no slack.”

Frances Rice, who stopped by Marte’s bodega for a bacon, egg, and cheese, says she’s trying to work out how to cope with less slack in her budget as prices rise. She says there’s always a silver lining.

“It means that I buy a good breakfast and stretch it to lunch and don’t eat again until I get home, which means I lose weight,” she said. “Got to look at the brighter side of things, because you know what? Either way, if you got to move, you’ve got to pay. If you’re hungry, you have to eat.”

What started as a $4 trillion effort during President Joe Biden’s first months in office to rebuild America’s public infrastructure and family support systems have ended up a much slimmer, but not unsubstantial, compromise package of inflation-fighting health care, climate change, and deficit reduction strategies that appears headed toward quick votes in Congress.

Lawmakers are pouring over the $739 billion proposal struck by two top negotiators, Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer and holdout Sen. Joe Manchin, the conservative West Virginia Democrat who rejected Biden’s earlier drafts but surprised colleagues late Wednesday with a new one.

What’s in, and out, of the Democrats’ 725-page “Inflation Reduction Act of 2022” as it stands now:

LOWER PRESCRIPTION DRUG COSTS

Launching a long-sought goal, the bill would allow the Medicare program to negotiate prescription drug prices with pharmaceutical companies, saving the federal government some $288 billion over the 10-year budget window.

Those new revenues would be put back into lower costs for seniors on medications, including a $2,000 out-of-pocket cap for older adults buying prescriptions from pharmacies.

The money would also be used to provide free vaccinations for seniors, who now are among the few not guaranteed free access, according to a summary document.

HELP PAY FOR HEALTH INSURANCE

The bill would extend the subsidies provided during the COVID-19 pandemic to help some Americans who buy health insurance on their own.

Under earlier pandemic relief, the extra help was set to expire this year. But the bill would allow the assistance to keep going for three more years, lowering insurance premiums for people who are purchasing their own health care policies.

‘SINGLE BIGGEST INVESTMENT IN CLIMATE CHANGE IN U.S. HISTORY

The bill would invest $369 billion over the decade in climate change-fighting strategies including investments in renewable energy production and tax rebates for consumers to buy new or used electric vehicles.

It’s broken down to include $60 billion for a clean energy manufacturing tax credit and $30 billion for a production tax credit for wind and solar, seen as ways to boost and support the industries that can help curb the country’s dependence on fossil fuels.

For consumers, there are tax breaks as incentives to go green. One is a 10-year consumer tax credit for renewable energy investments in wind and solar. There are tax breaks for buying electric vehicles, including a $4,000 tax credit for the purchase of used electric vehicles and $7,500 for new ones.

In all, Democrats believe the strategy could put the country on a path to cut greenhouse gas emissions by 40% by 2030, and “would represent the single biggest climate investment in U.S. history, by far.”

HOW TO PAY FOR ALL OF THIS?

The biggest revenue-raiser in the bill is a new 15% minimum tax on corporations that earn more than $1 billion in annual profits.

It’s a way to clamp down on some 200 U.S. companies that avoid paying the standard 21% corporate tax rate, including some that end up paying no taxes at all.

The new corporate minimum tax would kick in after the 2022 tax year, and raise some $313 billion over the decade.

Money is also raised by boosting the IRS to go after tax cheats. The bill proposes an $80 billion investment in taxpayer services, enforcement, and modernization, which is projected to raise $203 billion in new revenue — a net gain of $124 billion over the decade.

The bill sticks with Biden’s original pledge not to raise taxes on families or businesses making less than $400,000 a year.

The lower drug prices for seniors are paid for with savings from Medicare’s negotiations with the drug companies.

EXTRA MONEY TO PAY DOWN DEFICITS

With $739 billion in the new revenue and some $433 billion in new investments, the bill promises to put the difference toward deficit reduction.

Federal deficits spiked during the COVID-19 pandemic when federal spending soared and tax revenues fell as the nation’s economy churned through shutdowns, closed offices, and other massive changes.

The nation has seen deficits rise and fall in recent years. But overall federal budgeting is on an unsustainable path, according to the Congressional Budget Office, which put out a new report this week on long-term projections.

WHAT’S LEFT BEHIND

This latest package after 18 months of start-stop negotiations leaves behind many of Biden’s more ambitious goals.

While Congress did pass a $1 trillion bipartisan infrastructure bill for the highway, broadband, and other investments that Biden signed into law last year, the president’s and the party’s other priorities have slipped away.

Among them, is a continuation of a $300 monthly child tax credit that was sending money directly to families during the pandemic and is believed to have widely reduced child poverty.

Also gone, for now, are plans for free pre-kindergarten and free community college, as well as the nation’s first paid family leave program that would have provided up to $4,000 a month for births, deaths, and other pivotal needs.

The Federal Reserve on Wednesday raised its benchmark interest rate by hefty three-quarters of a point for a second straight time in its most aggressive drive in more than three decades to tame high inflation.

The Fed’s move will raise its key rate, which affects many consumer and business loans, to a range of 2.25% to 2.5%, its highest level since 2018.

Speaking at a news conference after the Fed’s latest policy meeting, Chair Jerome Powell offered mixed signals about the central bank’s likely next moves. He stressed that the Fed remains committed to defeating chronically high inflation while holding out the possibility that it may soon downshift to smaller rate hikes.

And even as worries grow that the Fed’s efforts could eventually cause a recession, Powell passed up several opportunities to say the central bank would slow its hikes if a recession occurred while inflation was still high.

Roberto Perli, an economist at Piper Sandler, an investment bank, said the Fed chair emphasized that “even if it caused a recession, bringing down inflation is important.”

But Powell’s suggestion that rate hikes could slow now that its key rate is roughly at a level that is believed to neither support nor restrict growth helped ignite a powerful rally on Wall Street, with the S&P 500 stock market index surging 2.6%. The prospect of lower interest rates generally fuels stock market gains.

At the same time, Powell was careful during his news conference not to rule out another three-quarter-point hike when the Fed’s policymakers next meet in September. He said that rate decisions will depend upon what emerges from the many economic reports that will be released between now and then.

“I do not think the U.S. is currently in a recession,” Powell said at his news conference in which he suggested that the Fed’s rate hikes have already had some success in slowing the economy and possibly easing inflationary pressures.

The central bank’s decision follows a jump in inflation to 9.1%, the fastest annual rate in 41 years, and reflects its strenuous efforts to slow price gains across the economy. By raising borrowing rates, the Fed makes it costlier to take out a mortgage or an auto or business loan. Consumers and businesses then presumably borrow and spend less, cooling the economy and slowing inflation.

The surge in inflation and fear of a recession have eroded consumer confidence and stirred public anxiety about the economy, which is sending frustratingly mixed signals. And with the November midterm elections nearing, Americans’ discontent has diminished President Joe Biden’s public approval ratings and increased the likelihood that the Democrats will lose control of the House and Senate.

The Fed’s moves to sharply tighten credit have torpedoed the housing market, which is especially sensitive to interest rate changes. The average rate on a 30-year fixed mortgage has roughly doubled in the past year, to 5.5%, and home sales have tumbled.

Consumers are showing signs of cutting spending in the face of high prices. And business surveys suggest that sales are slowing. The central bank is betting that it can slow growth just enough to tame inflation yet not so much as to trigger a recession — a risk that many analysts fear may end badly.

At his news conference, Powell suggested that with the economy slowing, demand for workers easing modestly, and wage growth possibly peaking, the economy is evolving in a way that should help reduce inflation.

“Are we seeing the slowdown in economic activity that we think we need?” he asked. “There’s some evidence that we are.”

The Fed chair also pointed to measures that suggest that investors expect inflation to fall back to the central bank’s 2% target over time as a sign of confidence in its policies.

Powell also stood by forecast Fed officials made last month that their benchmark rate will reach a range of 3.25% to 3.5 % by year’s end and roughly a half-percentage point more in 2023. That forecast, if it holds, would mean a slowdown in the Fed’s hikes. The central bank would reach its year-end target if it were to raise its key rate by a half-point when it meets in September and by a quarter-point at each of its meetings in November and December.

With the Fed having now imposed two straight substantial rate hikes, “I do think they’re going to tiptoe from here,” said Thomas Garretson, senior portfolio strategist at RBC Wealth Management.

On Thursday, when the government estimates the gross domestic product for the April-June period, some economists think it may show that the economy shrank for a second straight quarter. That would meet one longstanding assumption for when a recession has begun.

But economists say that wouldn’t necessarily mean a recession had started. During those same six months when the overall economy might have contracted, employers added 2.7 million jobs — more than in most entire years before the pandemic. Wages are also rising at a healthy pace, with many employers still struggling to attract and retain enough workers.

Still, slowing growth puts the Fed’s policymakers in a high-risk quandary: How high should they raise borrowing rates if the economy is decelerating? Weaker growth, if it causes layoffs and raises unemployment, often reduces inflation on its own.

That dilemma could become an even more consequential one for the Fed next year, when the economy may be in worse shape and inflation will likely still exceed the central bank’s 2% target.

“How much recession risk are you willing to bear to get (inflation) back to 2%, quickly, versus over the course of several years?” asked Nathan Sheets, a former Fed economist who is global chief economist at Citi. “Those are the kinds of issues they’re going to have to wrestle with.”

Economists at Bank of America foresee a “mild” recession later this year. Goldman Sachs analysts estimate a 50-50 likelihood of a recession within two years.

The U.S. economy is caught in an awkward, painful place. A confusing one, too.

Growth appears to be sputtering, home sales are tumbling and economists warn of a potential recession ahead. But consumers are still spending, businesses keep posting profits and the economy keeps adding hundreds of thousands of jobs each month.

In the midst of it all, prices have accelerated to four-decade highs, and the Federal Reserve is desperately trying to douse the inflationary flames with higher interest rates. That’s making borrowing more expensive for households and businesses.

The Fed hopes to pull off the triple axel of central banking: Slow the economy just enough to curb inflation without causing a recession. Many economists doubt the Fed can manage that feat, a so-called soft landing.

Surging inflation is most often a side effect of a red-hot economy, not the current tepid pace of growth. Today’s economic moment conjures dark memories of the 1970s, when scorching inflation co-existed, in a kind of toxic brew, with slow growth. It hatched an ugly new term: stagflation.

The United States isn’t there yet. Though growth appears to be faltering, the job market still looks quite strong. And consumers, whose spending accounts for nearly 70% of economic output, are still spending, though at a slower pace.

So the Fed and economic forecasters are stuck in uncharted territory. They have no experience analyzing the economic damage from a global pandemic. The results so far have been humbling. They failed to anticipate the economy’s blazing recovery from the 2020 recession — or the raging inflation it unleashed.

Even after inflation accelerated in the spring of last year, Fed Chair Jerome Powell and many other forecasters downplayed the price surge as merely a “transitory” consequence of supply bottlenecks that would fade soon.

It didn’t.

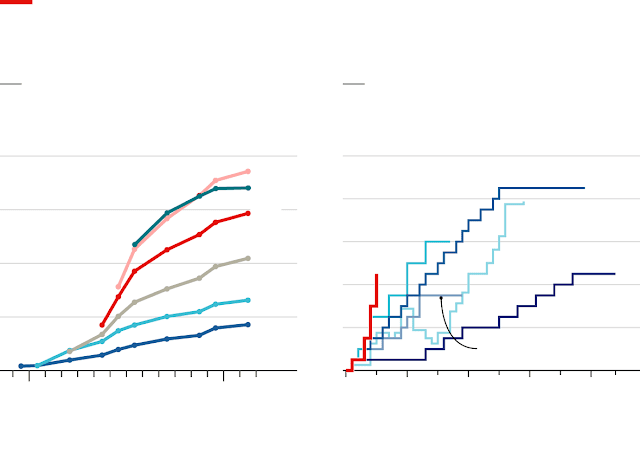

Now the central bank is playing catch-up. It’s raised its benchmark short-term interest rate three times since March. Last month, the Fed increased its rate by three-quarters of a percentage point, its biggest hike since 1994. The Fed’s policymaking committee is expected to announce another three-quarter-point hike Wednesday.

Economists now worry that the Fed, having underestimated inflation, will overreact and drive rates ever higher, imperiling the economy. They caution the Fed against tightening credit too aggressively.

“We don’t think a sledgehammer is necessary,” Ian Shepherdson, chief economist at Pantheon Macroeconomics, said this week.

Here’s a look at the economic vital signs that are sending frustratingly mixed signals to policymakers, businesses, and forecasters:

___

THE OVERALL ECONOMY

As measured by the nation’s gross domestic product — the broadest gauge of output — the economy has looked positively sickly so far this year. And steadily higher borrowing rates, engineered by the Fed, threaten to make things worse.

“Recession is likely,” said Vincent Reinhart, a former Fed economist who is now chief economist at Dreyfus and Mellon.

After growing at a 37-year high of 5.7% last year, the economy shrank at a 1.6% annual pace from January through March. For the April-June quarter, forecasters surveyed by the data firm FactSet estimate that growth equaled a scant 0.95% annual rate from April through June. (The government will issue its first estimate of April-June growth on Thursday.)

Some economists foresee another economic contraction for the second quarter. If that happened, it would further escalate recession fears. One informal definition of a recession is two straight quarters of declining GDP. Yet that definition isn’t the one that counts.

The most widely accepted authority is the National Bureau of Economic Research, whose Business Cycle Dating Committee assesses a wide range of factors before declaring the death of an economic expansion and the birth of a recession. It defines a recession as “a significant decline in economic activity that is spread across the economy and that lasts more than a few months.”

In any case, the economic drop in the January-March quarter looked worse than it actually was. It was caused by factors that don’t mirror the economy’s underlying health: A widening trade deficit, reflecting consumers’ robust appetite for imports, shaved 3.2 percentage points off first-quarter growth. A post-holiday-season drop in company inventories subtracted an additional 0.4 percentage point.

Consumer spending, measured at a modest 1.8% annual rate from January through March, is still growing. Americans are losing confidence, though: Their assessment of economic conditions six months from now has reached its lowest point since 2013 June, according to the Conference Board, a research group.

___

INFLATION

What’s agitating consumers is no secret: They’re reeling from painful prices at gasoline stations, grocery stores, and auto dealerships.

The Labor Department’s consumer price index skyrocketed 9.1% in June from a year earlier, a pace not seen since 1981. The price of gasoline has jumped 61% over the past year, airfares 34%, eggs 33%.

And despite widespread pay raises, prices are surging faster than wages. In June, average hourly earnings slid 3.6% from a year earlier adjusting for inflation, the 15th straight monthly drop from a year earlier.

And on Monday, Walmart, the nation’s largest retailer, lowered its profit outlook, saying that higher gas and food prices were forcing shoppers to spend less on many discretionary items, like new clothing.

The price spikes have been ignited by a combination of brisk consumer demand and global shortages of factory parts, food, energy, and labor. And so the Fed is now aggressively raising rates.

“There is a risk of overdoing it,” warned Ellen Gaske, an economist at PGIM Fixed Income. “Because inflation is so bad right now, they are focused on the here and now of each monthly CPI report. The latest one showed no letup.’’

___

JOBS

Despite inflation, rate hikes, and declining consumer confidence, one thing has remained solid: The job market, the most crucial pillar of the economy. Employers added a record 6.7 million jobs last year. And so far this year, they’re adding an average of 457,000 more each month.

The unemployment rate, at 3.6% for four straight months, is near a half-century low. Employers have posted at least 11 million job openings for six consecutive months. The government says there are two job openings, on average, for every unemployed American, the highest such ratio on record.

Job security and the opportunity to advance to better positions are providing the confidence and financial wherewithal for Americans to spend and keep the job machine churning.

Still, it’s unclear how long a hiring boom will last. In keeping up their spending in the face of high inflation, Americans have been drawing down the heavy savings they built up during the pandemic. That won’t last indefinitely. And the Fed’s rate hikes mean it’s increasingly expensive to buy a house, a car, or a major appliance on credit.

The weekly number of Americans applying for unemployment benefits, a proxy for layoffs and a bellwether for where the job market may be headed, reached 251,000 in the most recent reading. That’s still quite low by historic standards, but it’s the most since November.

___

MANUFACTURING

COVID-19 kept millions of Americans cooped up at home. But it didn’t stop them from spending. Unable to go out to restaurants, bars and movie theaters, people instead loaded up on factory-made goods — appliances, furniture, exercise equipment.

Factories have enjoyed 25 consecutive months of expansion, according to the Institute for Supply Management’s manufacturing index. Customer demand has been strong, though supply chain bottlenecks have made it hard for factories to fill orders.

Now, the factory boom is showing signs of strain. The ISM’s index dropped last month to its lowest level in two years. New orders declined. Factory hiring dropped for a second straight month.

A key factor is that the Fed’s rate hikes are heightening borrowing costs and the value of the U.S. dollar against other currencies, a move that makes American goods more expensive overseas.

“We doubt the outlook for manufacturing will improve any time soon,” Andrew Hunter, senior U.S. economist at Capital Economics, wrote this month. “Weakening global growth and the drag from the stronger dollar look set to keep U.S. manufacturers under pressure over the coming months.’’

Still, the government reported Wednesday that orders for high-cost factory goods jumped 1.9% from May to June on an uptick in orders for automobiles and a surge in orders for military aircraft.

___

HOUSING

No sector of the U.S. economy is more sensitive to interest rate increases than housing. And the Fed’s hikes and the prospect of steadily tighter credit are taking a toll.

Mortgage rates have risen along with the Fed’s benchmark rate. The average rate on a 30-year fixed-rate mortgage hit 5.54% last week, nearly double its level a year earlier.

The government reported Tuesday that sales of new single-family homes fell 8% last month from May and 17% from June 2021. And sales of previously occupied homes dropped in June for a fifth straight month. They’re down more than 14% from June 2021.

In response to the rapidly slowing home market, builders are cutting back. Construction of single-family homes dropped last month to its lowest level since March 2020, at the height of pandemic lockdowns.