Twitter Inc. is cutting back on its physical office space in several global markets, including San Francisco, New York, and Sydney, as the company cuts costs and leans harder into remote work.

Twitter will significantly decrease its corporate presence in San Francisco by vacating an office on Tenth Street directly behind the Market Street headquarters, according to an email sent to employees on Wednesday. Twitter currently occupies multiple floors in the building. It has also scrapped plans to open an office across the Bay in Oakland.

The company may close its office in Sydney and is considering plans to shutter several other offices once leases expire, including those in Seoul; Wellington, New Zealand; Osaka, Japan; Madrid; Hamburg, Germany; and Utrecht, The Netherlands, according to the memo. It may find alternative office space in some of those locations.

Corporate space in other key markets will be reduced, including Tokyo, Mumbai, New Delhi, Dublin, and New York. Twitter isn’t planning job cuts, according to the email.

“I want to make it clear that this does not change our commitment to the work in each of these markets,” wrote Dalana Brand, Twitter’s chief people officer. “If certain offices were to close, there would be no impact” to Twitter workers’ jobs; they would simply transition to full-time work-from-home employees, she said.

A spokesperson said the decisions don’t affect current headcount or employee roles, “and we’ll continue to support and regularly meet with our customers to help them launch something new and connect with what’s happening on Twitter.” The company had more than 7,500 employees at the end of 2021.

The changes are the latest in a series of cost cuts from the social media company, which has pointed to global economic factors as a reason for the reductions. Twitter implemented a hiring freeze in early May, and Chief Executive Officer Parag Agrawal also announced pullbacks in marketing and corporate travel and asked employees to be more thoughtful with their spending. A companywide outing scheduled for early 2023 at Disneyland was also canceled.

Twitter is tightening the reins after the board agreed to sell the company to Tesla Inc. CEO Elon Musk for $44 billion in late April. But Musk has since tried to back out of the deal, and the two sides are now in the middle of a contentious legal battle. Twitter is suing Musk in Delaware Chancery Court to force him to complete the deal with a trial planned for sometime in October. Musk had previously told advisors and bankers that he was planning cost cuts at the company once he took over. The billionaire also has been adamant about workers coming into the office. In June he sent an email to employees at Tesla requiring them to be in the office 40 hours a week.

Turning the lights out in global offices solidifies a major cultural change for Twitter, which announced in mid-2020 that its employees could work remotely forever as the world hunkered down during the pandemic. The prospect of permanent remote work has raised questions about the need for corporate office space, especially in expensive cities like San Francisco and New York, prompting several big tech companies to reconsider their real estate needs.

That shift has hit San Francisco particularly hard, and the city is actively working to restore its appeal to businesses and tourists. Block Inc., another company that moved to permanent remote work during the pandemic under CEO Jack Dorsey, has cut down on its San Francisco office space. Salesforce Inc. has reduced its office footprint multiple times since the pandemic, and earlier this spring decided to lease 40% of its 43-story namesake tower, according to the San Francisco Chronicle.

Meanwhile, on the East Coast, Amazon.com Inc. cut back on the amount of space it had intended to lease from JPMorgan Chase & Co. at Hudson Yards, reducing the square footage it aims to take over, people familiar with the company’s plans have said. Facebook parent Meta Platforms Inc. decided against taking an additional 300,000 square feet (27,870 square meters) of space in a building in Manhattan near where it’s already located and is also pausing plans to further build out new offices in Hudson Yards.

Just a month ago, media executives expressed optimism that their companies were well positioned for an economic slowdown.

Vox Media may have injected a dose of reality into the industry Wednesday.

The privately held digital media company is laying off 39 employees, according to a person familiar with the matter, as well as slowing down hiring and reducing non-essential expenses. The layoffs affect employees in sales, recruiting, and certain editorial teams.

New York Magazine, which is owned by Vox Media, isn’t affected, said the person, who asked not to be named because the decisions are private. The company’s brands also include namesake outlet Vox, The Verge, Curbed, and Now This. A spokesperson for Vox Media declined to comment.

In a memo to staff, Vox Media CEO Jim Bankoff directly cited deteriorating economic conditions for the decision.

“The current economic conditions are impacting companies like ours in multiple ways, with supply chain issues reducing marketing and advertising budgets across industries and economic pressures changing the ways that consumers spend,” Bankoff wrote in the memo obtained by CNBC. “Our aim is to get ahead of greater uncertainty by making difficult but important decisions to pare back on initiatives that are lower priority or have lower staffing needs in the current climate.”

He said in the memo that the cuts affect “under 2% of the company.” Earlier this year, Vox Media acquired Group Nine, adding hundreds of employees to the company. Vox derives the majority of its revenue from advertising.

Several employees at Thrillist, one of the brands acquired in the Group Nine deal, tweeted Wednesday they’ve been laid off.

The digital media industry hasn’t gotten the valuation bump executives hoped might happen with BuzzFeed’s decision to go public. BuzzFeed went public via a special purpose acquisition company at $10 per share in December. Seven months later, BuzzFeed shares are below $2.

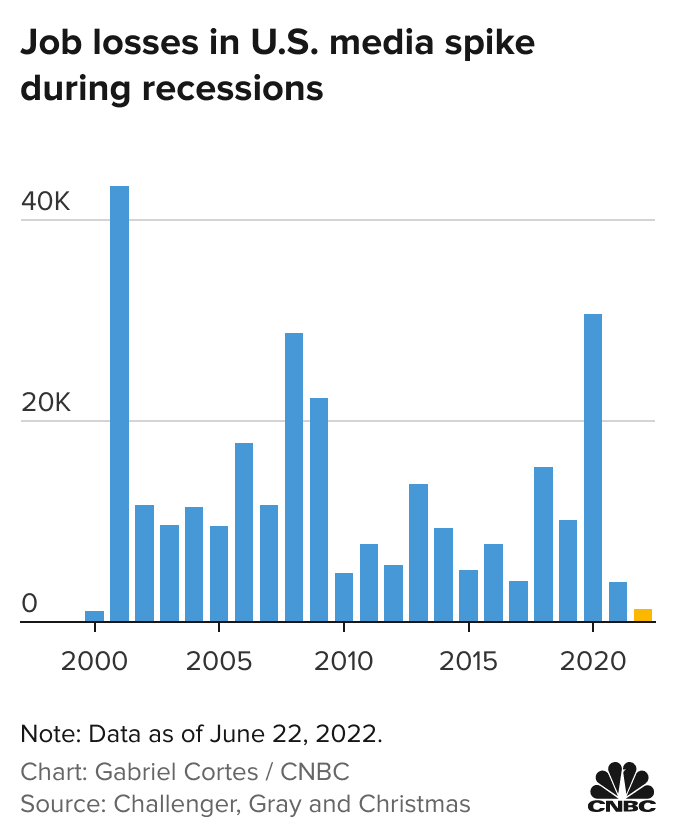

Vox Media’s decision to cut staff may be the tip of the iceberg for media. Since 2000, on a year-by-year basis, the biggest three years for job losses in the industry all coincided with recessions — the 2020 Covid-19 pullback, the 2007-09 financial crisis, and the 2001 dot-com bubble bust, according to data from Challenger, Gray & Christmas.

Officially, the NBER defines a recession as “a significant decline in economic activity that is spread across the economy and lasts more than a few months.”

More than 60% of respondents to a CNBC Survey this week predicted the Federal Reserve’s efforts to rein in inflation by hiking rates will lead to a recession. Of those who predict a recession in the next 12 months, most believe it will begin in December. U.S. inflation rose 9.1% in June, the highest jump in 40 years.

It's been seven months since his employer ordered the last of its remote workers to return to the office, but Ben, a 36-year-old business analyst at a bank in California, has quietly defied the mandate. Employees in his role are supposed to be on-site at least three times a week. Ben goes in maybe once a month.

"I just never started coming in," he tells me, asking me not to use his real name for fear of retaliation. "I don't like the commute. I get more done at home. I have fewer distractions, and I'm in a controlled environment."

Two years into the pandemic, much of corporate America has given employees two choices: drag themselves back to their cubicle or quit. Plenty has chosen the former. And in the Great Resignation, many others have opted for the latter. But Ben is among those who have carved out a third way: refuse to comply with the back-to-work orders and hope you get away with it.

It's a risky gambit — but there are a lot more return-to-office rulebreakers than you might expect. Take the results of a national work-from-home survey conducted by economists at three universities. At companies requiring employees to come in five days a week, fewer than 49% of employees are actually doing so — meaning that more than half of their workforces are flat-out refusing to comply. And even at companies that require attendance for only part of the week, there's still a sizable share of employees — as high as 19% — who aren't coming in as much as they're supposed to. Translation: For every four goody-two-shoes who have meekly returned to the office, there's an employee like Ben who's thumbing their nose at the boss.

"There's a lot of people who are refusing to return to the office," Nicholas Bloom, an economics professor at Stanford University who co-runs the survey, tells me. "This is causing problems for middle management, who have to then go on and execute these policies."

What's even more surprising is that companies are essentially letting the scofflaws get away with it. The most common repercussion employees reported in the work-from-home survey was? Nothing at all. And only 12% of respondents say their employer has fired someone for refusing to come in. Ben's manager actually gave him informal approval to break his company's policy, he says, because "she doesn't care" that he's not coming into the office as instructed. As the war over working from home heats up, the Great Resignation is giving way to another battlefront: the Great Resistance. White-collar professionals are calling their employers' bluff — and they're finding that mandatory office attendance isn't so mandatory after all.

Risking a mass exodus

So what's stopping employers from coming down hard on their office avoiders? It isn't because they're worried about getting sued: Aside from a few exceptions — when someone, say, has a disability — companies can generally require their employees to come into the office. Their hesitation lies more in the realities of today's job market, coupled with the sheer size of the return-to-office revolt. "With the tight labor market, employers are not in a position to lose their top talent," says Ann Marie Zaletel, an employment attorney at the law firm Seyfarth Shaw. "They're not in a position to fire 50% of their workforce."

Employers worry that even small punishments for rulebreakers could be enough to anger workers, spurring them to look for employment elsewhere. That's why, in the national survey, employees report that even pay reductions (17%), verbal reprimands (19%), and negative performance reviews (14%) have been relatively rare.

Take the case of Stanley, a technical writer whose experience offers a cautionary tale for companies that are thinking about enforcing their return-to-office policies. Last summer, his employer called everyone back in for four days a week. Stanley, who asked that his name be altered to protect his future job prospects, complied for the first few weeks. "But then I was just kind of like, 'This is dumb,'" he tells me. "There's no point in doing this. I'm actually less productive in the office." Others on his team felt similarly, so together, they quietly stopped going in.

Stanley's manager noticed and ordered him to come in. When Stanley refused to acquiesce, he soon found himself being confronted on a weekly basis by managers higher and higher up the corporate ladder. The threats stressed him out, but they remained just that: threats. "They didn't fire anybody," he says. "There were no performance-improvement plans. They really weren't doing anything about it. They were just kicking and screaming and asking for their way, and when it came down to it, they couldn't get their way."

After standing his ground for a year, Stanley finally got so sick of the reprimands that he started interviewing at companies that were happy to let him work from home. He landed a job right away. So did many of his colleagues. His former team of 15 or so has now shrunk to about three. "I can't even imagine what the people who are still there are having to deal with as far as the workload," he says.

Happy hours, free lunch, Lizzo

Because of the risk of a mass exodus, many companies are resorting to a softer approach. Some are trying to persuade their staff of the collective benefits of being together in person — to promote mentoring, say, or to foster greater collaboration and creativity. Others are providing in-office perks, such as happy hours and free lunches — or, in Google's case, hiring Lizzo to perform a private return-to-office concert. They're "using the carrot approach rather than the stick approach," says Zaletel, the employment lawyer.

Zaletel says her clients have reported, "some effectiveness" with the let's-make-the-office-fun tactic. But free meals or booze may not do much to sway office avoiders in the face of crushing commutes and childcare obligations. (Even at Google's Lizzo concert, one employee in the audience could be heard screaming "Propaganda! Propaganda!") Sure, there are plenty of employees who want to come to the office. But those who don't, such as Stanley and Ben, often feel so strongly about protecting their right to work from home that they're willing to risk being fired. Last year, when Bloom and his coauthors asked Americans who were working from home at the time what they would do if they were told to return to the office full time, 42% said they would either quit on the spot or look for a new job that would allow them to work from home.

Though playing hardball may risk a wave of resignations, looking the other way as employees flagrantly violate company policy isn't exactly a great option. "It makes management look weak," Bloom says. So what's a company to do in the face of this lose-lose scenario?

The first instinct of many older executives has been to gripe about "kids these days." But a better start would be to question the policy itself. "If 50% of people are refusing," Bloom says, "it tells you there's something problematic. Companies are asking employees to come in for more days than they need to." The rules, he says, are often "bad from the get-go. It's CEOs setting aggressive return-to-office policies that aren't in line with what the company needs."

Playing hardball

Bloom doesn't name any names, but the companies that have issued the strictest return-to-office policies are the ones led by executives who seem to loathe the very idea of remote work. At Tesla and SpaceX, for example, Elon Musk has threatened work-from-homers with termination. "Anyone who wishes to do remote work must be in the office for a minimum (and I mean *minimum*) of 40 hours per week or depart Tesla," he warned employees in a memo. "If you don't show up, we will assume you have resigned." Asked on Twitter what he thought of people who viewed coming into an office as an antiquated concept, he offered a terse reply: "They should pretend to work somewhere else."

Some leading Wall Street banks, as my colleagues at Insider have reported, have started tracking employee badge swipes to see who's showing up. At JPMorgan, where CEO Jamie Dimon has said remote work "doesn't work for those who want to hustle," the swipe data is being used to create dashboards of attendance. Managers then use the data to enforce in-office quotas and crack down on staffers who aren't coming in enough. At Goldman, where CEO David Solomon has called working from home "an aberration that we are going to correct as quickly as possible," employees have been warned that their manager may reprimand them if they're not complying. If they're not at their desks by 10 a.m., they'll be marked as absent.

So far, few employers have been willing to go to such extreme lengths to rein in violators. But if we're hit by a recession and jobs get scarce, employers won't be so worried about losing their workers to competitors. And as more businesses start to enforce their back-to-office edicts, such hardline approaches could gradually become the norm. As we saw last year with the debate over vaccine mandates, few employers aside from hospitals dared to require them at first. But once mandates reached a sort of critical mass, they became widely implemented. Employers right now are in a similar wait-and-see mode. "No employer wants to go out on a limb and be the first employer" to threaten termination, Zaletel says, because "their competitors will swoop up their top talent in this really competitive market."

For now, the US's office-reluctant professionals are enjoying the freedom and flexibility of working from home that their employers don't want them to have. And many are determined to milk the Great Resistance for as long as they can get away with it. When I ask Stanley, who resisted his employer's return-to-office mandate for a full year, what his advice would be to would-be rulebreakers, he sounds more like a rebel strategist than a technical writer.

"The best thing I would recommend is having a backup plan in place, whether that's a savings account that can weather you until you get a new job or a conditional job offer," he says. "Taking that leap sometimes is good because it shows you where your values are and what you're willing to do to stand up for them."