Angel Hope looked at the math test and felt lost. He had just graduated near the top of his high school class, winning scholarships from prestigious colleges. But on this test — a University of Wisconsin exam that measures what new students learned in high school — all he could do was guess.

It was like the disruption of the pandemic was catching up to him all at once.

Nearly a third of Hope’s high school career was spent at home, in virtual classes that were hard to follow and easy to brush aside. Some days he skipped school to work extra hours at his job. Some days he played games with his brother and sister. Other days he just stayed in bed.

Algebra got little of his attention, but his teachers kept giving him good grades amid a school-wide push for leniency.

“It was like school was optional. It wasn’t a mandatory thing,” said Hope, 18, of Milwaukee. “I feel like I didn’t really learn anything.”

Across the country, there are countless others like him. Hundreds of thousands of recent graduates are heading to college this fall after spending more than half their high school careers dealing with the upheaval of a pandemic. They endured a jarring transition to online learning, the strains from teacher shortages, and profound disruptions to their home lives. And many are believed to be significantly behind academically.

Colleges could see a surge in students unprepared for the demands of college-level work, education experts say. Starting a step behind can raise the risk of dropping out. And that can hurt everything from a person’s long-term earnings to the health of the country’s workforce.

The extent of the problem became apparent to Allison Wagner as she reviewed applications for All-In Milwaukee, a scholarship program that provides financial aid and college counseling to low-income students, including Hope.

Wagner, the group’s executive director, saw startling numbers of students who were granted permission to spend half the school day working part-time jobs their senior year, often at fast food chains or groceries. And she saw more students than ever who didn’t take math or science classes their senior year, often as a result of teacher shortages.

“We have so many students who are going on to college academically malnourished,” Wagner said. “There is no way they are going to be academically prepared for the rigor of college.”

Her group is boosting its tutoring budget and covering tuition for students in the program who take summer classes in math or science. Still, she fears the setbacks will force some students to take more than four years to graduate or, worse, drop out.

“The stakes are tremendously high,” she said.

Researchers say it’s clear that remote instruction caused learning setbacks, most sharply among Black and Hispanic students. For younger students, there’s still hope that America’s schools can accelerate the pace of instruction and close learning gaps. But for those who graduated in the last two years, experts fear many will struggle.

In anticipation of higher needs, colleges from New Jersey to California have been expanding “bridge” programs that provide summer classes, often for students from lower incomes or those who are the first in their families to attend college. Programs previously treated as orientation are taking on a harder academic edge, with a focus on math, science, and study skills.

In Hanceville, Alabama, Wallace State Community College this year tapped state money to create its first summer bridge program as it braces for an influx of underprepared students. Students could take three weeks of accelerated lessons in math and English in a bid to avoid remedial classes.

The school hoped to bring up to 140 students to campus, but just 10 signed up.

Other states have used federal pandemic relief to help colleges build summer programs. In Kentucky, which gave colleges $3.5 million for the effort this year, officials called it a “moral imperative.”

“We need these people to be our future workforce, and we need them to be successful,” said Amanda Ellis, a vice president of Kentucky’s Council on Postsecondary Education.

After the pandemic hit, Angel Hope worked up to 20 hours a week at his job with a local nonprofit aid group. He felt the time away from school was worth it for the money, especially when nobody was paying attention in the online classes. With his parents away at work, he often felt alone, shunning social media for days and eating ramen noodles for dinner.

“I think isolating myself was a little bit of my coping mechanism,” he said. “I was kind of like, ‘Keep it in a little bit and you’ll get through it eventually.’”

The pandemic led many high schoolers to disengage at a time when they would usually be preparing for college or careers, said Rey Saldaña, president and CEO of Communities in Schools, a nonprofit group that places counselors in public schools in 26 states.

His group worked in some districts where hundreds of students simply didn’t return after classrooms reopened. In Charlotte, North Carolina, the allure of steady paychecks kept many students away from school even after in-person classes resumed, said Shakaka Perry, a re-engagement coordinator for Communities in Schools.

Perry and her colleagues spent last school year bringing students back to school and getting them ready for graduation. But when she thinks about whether they’re ready for college, she has doubts: “It’s going to be an awakening.”

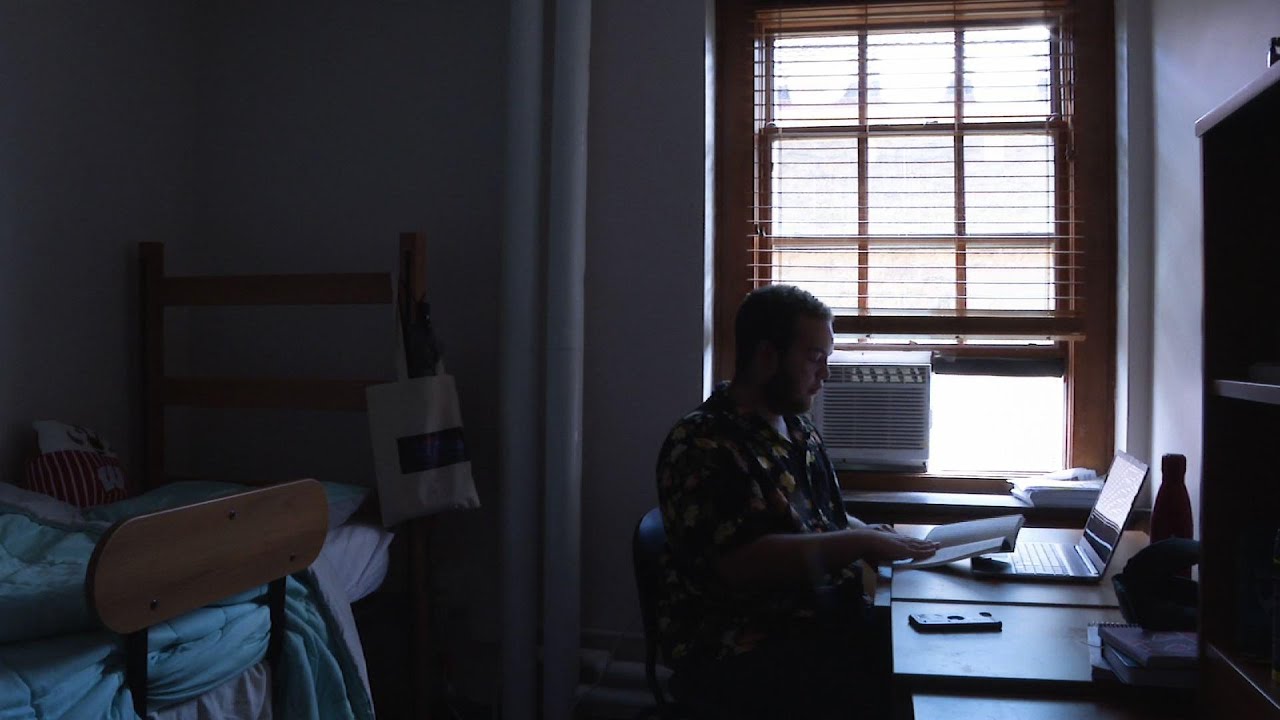

A couple months after struggling through his math placement test, Hope headed to the University of Wisconsin-Madison, for six weeks of intense classes in a summer bridge program. He took a math class that covered the ground he missed in high school, and he’s signed up to take calculus in the fall.

He also revived basic study skills that went dormant in high school. He started studying at the library. He got used to the rhythms of school, with assignments every day and tests every other week. He rediscovered what it’s like to enjoy school.

Most importantly, he says it changed his mindset: Now he feels like he’s there to learn, not just to get by.

“After this, I definitely feel prepared for college,” he said. “If I didn’t have this, I would be in a very bad place.”

___

The Associated Press education team receives support from the Carnegie Corporation of New York. The AP is solely responsible for all content.

___

Associated Press writer Carrie Antlfinger in Milwaukee contributed.

___

For more back-to-school coverage, visit: https://apnews.com/hub/back-to-school