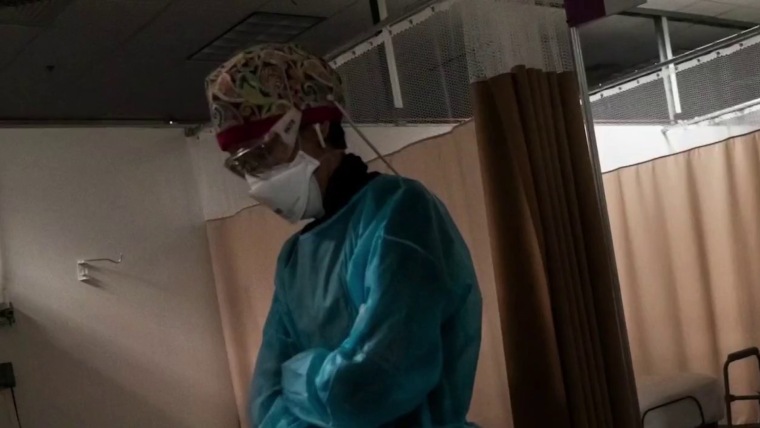

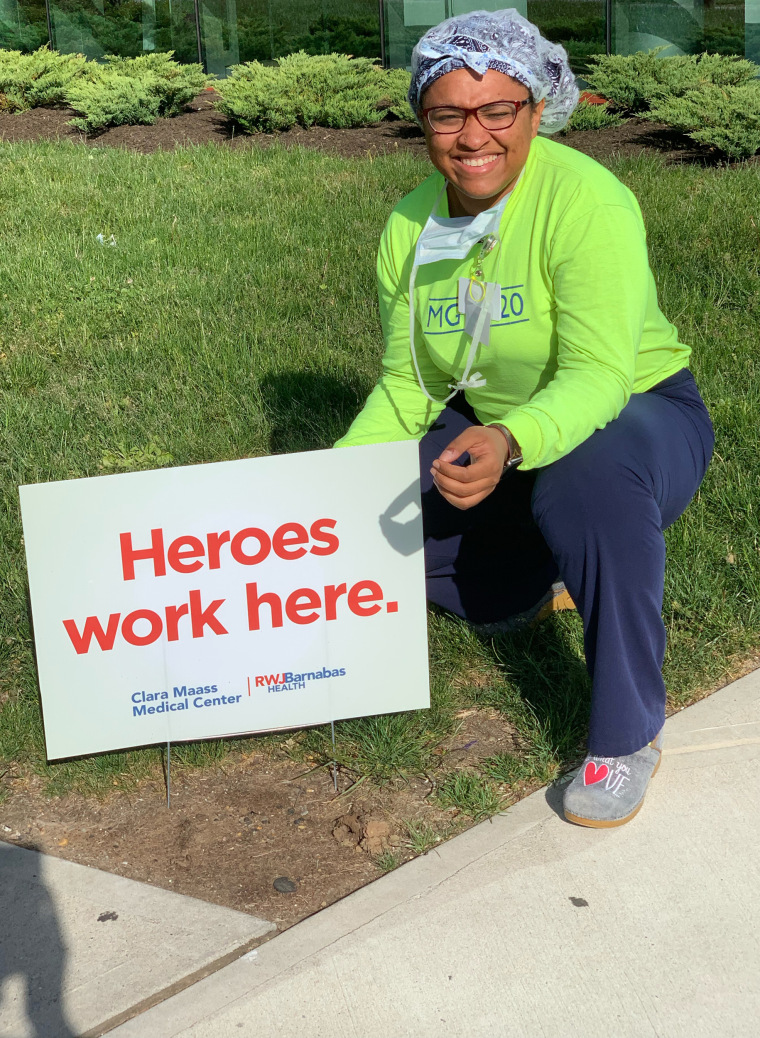

Working as a travel nurse in the early days of the Covid pandemic was emotionally exhausting for Reese Brown — she was forced to leave her young daughter with her family as she moved from one gig to the next, and she watched too many of her intensive care patients die.

“It was a lot of loneliness,” Brown, 30, said. “I’m a single mom, I just wanted to have my daughter, her hugs, and see her face and not just through FaceTime.”

But the money was too good to say no. In July 2020, she had started earning $5,000 or more a week, almost triple her pre-pandemic pay. That was the year the money was so enticing that thousands of hospital staffers quit their jobs and hit the road as travel nurses as the pandemic raged.

Two years later, the gold rush is over. Brown is home in Louisiana with her daughter and turning down work. The highest paid travel gigs she’s offered are $2,200 weekly, a rate that would have thrilled her pre-pandemic. But after two "traumatic" years of tending to Covid patients, she said, it doesn’t feel worth it.

“I think it’s disgusting because we went from being praised to literally, two years later, our rates dropped,” she said. “People are still sick, and people are still dying.”

The drop in pay doesn’t mean, however, that travel nurses are going to head back to staff jobs. The short-lived travel nurse boom was a temporary fix for a long-term decline in the profession that predates the pandemic. According to a report from McKinsey & Co., the United States may see a shortage of up to 450,000 registered nurses within three years barring aggressive action by health care providers and the government to recruit new people. Nurses are quitting, and hospitals are struggling to field enough staff to cover shifts.

Nine nurses around the country, including Brown, told NBC News they are considering alternate career paths, studying for advanced degrees, or exiting the profession altogether.

“We’re burned out, tired nurses working for $2,200 a week,” Brown said. People are leaving the field, she said, “because there’s no point in staying in nursing if we’re expendable.”

$124.96 an hour

Travel nursing seems to have started as a profession, industry experts say, in the late 1970s in New Orleans, where hospitals needed to add temporary staff to care for sick tourists during Mardi Gras. In the 1980s and the 1990s, travel nurses were often covering for staff nurses who were on maternity leave, meaning that 13-week contracts become common.

By 2000, over a hundred agencies provided travel contracts, a number that quadrupled by the end of the decade. It had become a lucrative business for the agencies, given the generous commissions that hospitals pay them. A fee of 40 percent on top of the nurse’s contracted salary is not unheard of, according to a spokesperson for the American Health Care Association, which represents long-term care providers.

Just before the pandemic, in January 2020, there were about 50,000 travel nurses in the U.S., or about 1.5 percent of the nation's registered nurses, according to Timothy Landhuis, vice president of research at Staffing Industry Analysts, an industry research firm. That pool doubled in size to at least 100,000 as Covid spread, and he says the actual number at the peak of the pandemic may have far exceeded that estimate.

By 2021, travel nurses were earning an average of $124.96 an hour, according to the research firm — three times the hourly rate of staff nurses, according to federal statistics.

That year, according to the 2022 National Health Care Retention & RN Staffing Report from Nursing Solutions Inc., a nurse recruiting firm, the travel pay available to registered nurses contributed to 2.47% of them leaving hospital staff jobs.

But then, as the rate of deaths and hospitalizations from Covid waned, the demand for travel nurses fell hard, according to industry statistics, as did the pay.

Demand dropped 42 percent from January to July this year, according to Aya Healthcare, one of the largest staffing firms in the country.

That doesn’t mean the travel nurses are going back to staff jobs.

Brown said she’s now thinking about leaving the nursing field altogether and has started her own business. Natalie Smith of Michigan, who became a travel nurse during the pandemic, says she intends to pursue an advanced degree in nursing but possibly outside of bedside nursing.

Pamela Esmond of northern Illinois, who also became a travel nurse during the pandemic, said she’ll keep working as a travel nurse, but only because she needs the money to retire by 65. She’s now 59.

“The reality is they don’t pay staff nurses enough, and if they would pay staff nurses enough, we wouldn’t have this problem,” she said. “I would love to go back to staff nursing, but on my staff job, I would never be able to retire.”

The coronavirus exacerbated issues that were already driving health care workers out of their professions, Landhuis said. “A nursing shortage was on the horizon before the pandemic,” he said.

According to this year’s Nursing Solutions staffing report, nurses are exiting the bedside at “an alarming rate” because of rising patient ratios, and their own fatigue and burnout. The average hospital has turned over 100.5% of its workforce in the past five years, according to the report, and the annual turnover rate has now hit 25.9%, exceeding every previous survey.

There are now more than 203,000 open registered nurse positions nationwide, more than twice the number just before the pandemic in January 2020, according to Aya Healthcare.

An obvious short-term solution would be to keep using travel nurses. Even with salaries falling, however, the cost of hiring them is punishing.

LaNelle Weems, executive director of Mississippi Hospital Association’s Center for Quality and Workforce, said hospitals can’t keep spending like they did during the peak of the pandemic.

“Hospitals cannot sustain paying these exorbitant labor costs,” Weems said. “One nuance that I want to make sure you understand is that what a travel agency charges the hospitals is not what is paid to the nurse.”

Ultimately, it’s the patients who will suffer from the shortage of nurses, whether they are staff or gig workers.

“Each patient added to a hospital nurse’s workload is associated with a 7%-12% increase in-hospital mortality,” said Linda Aiken, founding director of the University of Pennsylvania’s Center for Health Outcomes and Policy Research.

Nurses across the country told NBC News that they chose the profession because they cared about patient safety and wanted to be at the bedside in the first line of care.

“People say it’s burnout but it’s not,” Esmond said about why nurses are quitting. “It’s the moral injury of watching patients not being taken care of on a day-to-day basis. You just can’t take it anymore.”