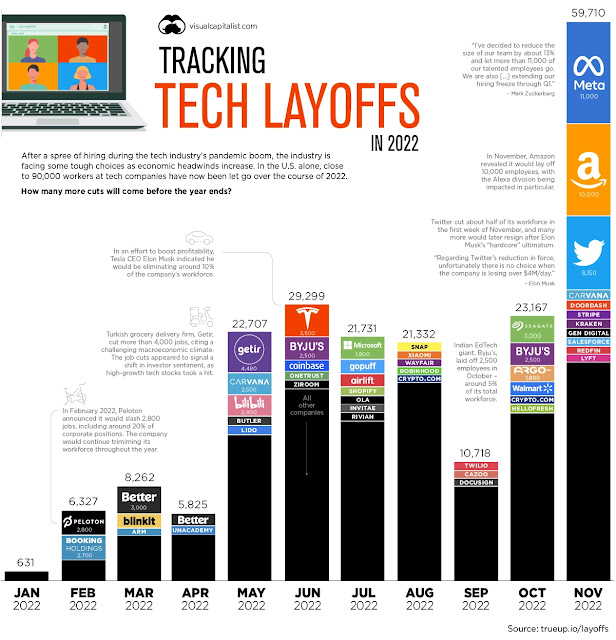

Today it’s difficult to read the news without seeing an announcement of layoffs. Just this week, Morgan Stanley announced it will reduce its workforce by 2%, Buzzfeed said it would cut headcount by 12%, and PepsiCo said it plans to cut “hundreds” of jobs. The same is true at Redfin (13%), Lyft (13%), Stripe (14%), Snap (20%), Opendoor (18%), Meta (13%), and Twitter (50%). So many companies have initiated layoffs recently that tech and HR entrepreneurs launched trackers like TrueUp Tech and to Layoffs.fyi dedicated to monitoring the staff reductions across the tech sector.

Traditionally, employers resort to layoffs during recessions to save money. Companies continue to cling to the idea that reducing staff will provide the best, fastest, or easiest solution to financial problems.

I’ve studied layoffs since 2009. In 2018, I wrote an article for HBR that explored how the short-term cost savings provided by a layoff are overshadowed by bad publicity, loss of knowledge, weakened engagement, higher voluntary turnover, and lower innovation — all of which hurt profits in the long run.

What’s Different About Layoffs Today

Those findings haven’t changed in the last four years. What’s different now is the larger social landscape in which today’s layoffs are unfolding. To make intelligent and humane staffing decisions in today’s economic turmoil, leaders must first understand three recent trends.

Word travels faster.

In the traditional pre-pandemic office environment, news of a reduction in force might have spread as workers saw the upset faces of their colleagues emerging from an unexpected meeting with their boss.

Today colleagues may be dispersed, but a single Slack or Teams message can simultaneously and instantly alert tens of thousands of employees around the world to news of a layoff. Whether companies want it this way or not, communication is simultaneously internal and external, spreading from employees to social media, journalists, and trade media that serve specific industries and the people who work in them.

Corporate decision-making is under a microscope.

Businesses have always needed to justify their actions, but today corporate reasoning is subjected to wider scrutiny in both traditional and social media. This is especially true in tech, whose products and services are deeply embedded in our daily lives and whose leaders have achieved celebrity status. A quick glance at any social media platform will reveal that customers are quick to share their strong opinions about the strategies companies pursue.

Stories about horrific layoffs have always been dismayingly easy to find. I once heard about a company that divided employees into two groups. One room was filled with people who were told they were losing their jobs. Just next door — and so loudly it could be heard — were the survivors, who were being told: “You are winners! You are why we can do even better!”

Today, poor treatment of employees looks short-sighted and is contrary to companies’ own interests. In the past, a company’s decision to eliminate positions may have been protested by a small group of labor rights advocates. Today, thanks to social media, anyone can challenge workforce reduction decisions, and ask, “Can’t they see that no one will want to work for a company that does that?”

The pandemic showed that companies have other options.

In the early months of the pandemic, some companies announced mass layoffs. But not everyone — Marc Benioff publicly pledged that Salesforce would enact a 90-day no-layoff policy [TS: Benioff promised not to make “significant” layoffs. Can we tweak this too, “pledged that Salesforce would make no “significant” layoffs for 90 days, and asked other companies to commit to doing the same?”?]. Many companies, including Starbucks, Bank of America, and Morgan Stanley assured staff that, barring a performance issue, jobs were secure through the end of 2020. Other CEOs made similar temporary no-layoff pledges to help stem workers’ anxiety.

These companies announced a different approach, including salary reductions for executives, furloughing employees instead of terminating, and even sometimes forgoing base salaries altogether for certain executives. Some CEOs offered grants to employees facing financial hardship or gave workers extra PTO to help ease the increased demands of caregiving.

In taking these actions, CEOs communicated that employees mattered. But these statements also left leaders exposed to charges of hypocrisy when many of them resorted to staff reductions later in 2020, despite record profits and stock buybacks.

What Hasn’t Changed About Layoffs

Research shows that layoffs continue to have detrimental long-term effects on individuals and companies.

Layoffs destroy trust.

Eighty-five percent of respondents rated job loss as their top concern in Edelman’s 2022 Trust Barometer. Layoffs break trust by severing the connection between effort and reward. The premise of a layoff is that if it weren’t for the economic conditions facing the firm, employees would keep their jobs as long as they perform them well.

The fact that this is a psychological contract rather than in most cases a legal one is beside the point. In the domain of trust, what matters is that employees are being asked to willingly be vulnerable to the power their company has as an employer, and trust that the company will act in ways that don’t violate their trust. Research finds that once betrayed, this trust is hard to recover.

Layoffs have a long-term impact on people’s health and finances.

One study found that being laid off ranked seventh among the most stressful life experiences — above divorce, a sudden and serious impairment of hearing or vision, or the death of a close friend. Experts advise that it takes, on average, two years to recover from the psychological trauma of losing a job.

For healthy employees without pre-existing health conditions, the odds of developing a new health condition rise by 83% in the first 15 to 18 months after a layoff, with the most common conditions being stress-related illnesses, including hypertension, heart disease, and arthritis. The psychological and financial pressure of being laid off can increase the risk of suicide by 1.3 to 3 times. Displaced workers have twice the risk of developing depression, four times the risk of substance abuse, and six times the risk of committing violent acts including partner and child abuse. The stress induced by a layoff can even impair fetal development.

Displaced workers, as a group, experience income losses that can last for the remainder of their careers: Workers who lost their jobs during the 1981 recession saw a 30% decline in earnings at the time of their layoff. Twenty years later, most still earned 20% less than workers who retained their jobs — the cumulative effect of unemployment, underemployment, and an inability to find work commensurate with their skills.

Layoffs negatively impact companies in real but hard-to-measure ways.

Since 1990, researchers have studied the effects of layoffs on firm performance to understand whether planned-for improvements are realized in practice. The results are less clear than one would expect.

The findings of two decades of profitability studies are equivocal: The majority of firms that conduct layoffs do not see improved profitability, whether measured by return on assets, return on equity, or return on sales. Layoffs are especially hard on the performance of companies with a high reliance on R&D, low capital intensity, and high growth. Market response to layoffs was also less positive than might be expected, with three-day share prices of firms conducting layoffs generally neutral. Higher valuations were given for layoffs perceived as helping firms in financial distress return to profitability as well as those that were strategic and forward-looking. Layoffs undertaken only for the purpose of reducing costs tended to lead to drops in share price.

Another study focused on Fortune 1000 firms between 2003 and 2007 — a period of economic prosperity — to try to minimize the confounding effects of layoffs undertaken during different economic conditions. Replicating earlier longitudinal studies, it found that layoffs do not, in general, offer immediate financial improvements. Firms conducting layoffs underperformed firms that did not conduct layoffs for the first two years, achieving comparable performance by year three on measures of return on assets, profit margin, and economic growth. The authors conclude, “For downsizing companies to gain a competitive advantage to outperform their competitors, it probably will take even longer.”

Layoffs have direct costs, including severance and the continuation of health benefits which can lead to substantial restructuring charges that eat into hoped-for margin improvements. As a thought experiment, multiply the salary of 11,000 Meta employees by four months — increasing it perhaps to five to account for an open-ended extra week of severance for every year worked. Add to that the cost of extending health benefits for six months … you can see how the numbers can add up.

But those year-one costs would not fully explain why companies that conduct layoffs underperform for nearly three years longer than those that do not. The reasons are in the well-researched hidden costs of layoffs. Employees who survive the layoff may struggle with anxiety, insecurity, low morale, sadness, and survivor guilt, which lead to disengagement and hinder job performance. Research shows show that anxiety about job security, grief for coworkers who were let go, and overwork can reduce innovation. Quality may decline as employees focus on improving productivity to keep their jobs. Managing talent becomes more difficult as existing staff resign. Reputational damage may make it harder to attract high-quality new hires.

The breadth of these effects explains how post-layoff underperformance happens — and how it can be missed since the impacts are dispersed throughout the firm in activities and functions that might not appear at first to relate to layoffs. There are many important reasons for restructuring and workforce reductions, including ownership changes through divestitures and M&A activity, efficiency improvements, down market conditions and financial challenges, and geographic and market changes.

The underperformance does lead, however, to an inescapable conclusion: Layoffs — and workforce change in general — still can be done smarter and better.

How to Be Smarter about Workforce Change

In the wake of the string of recent layoffs in tech, one economic historian observed: “Far from cutting-edge, these layoffs mark a revival of long-discredited corporate strategies. If the trend continues, history suggests these tech leaders will leave their companies severely crippled, at best.”

Recently, a number of CEOs of scaling startups have asked me for advice about maintaining trust while managing layoffs in this changing landscape. Here are some strategies I shared with them.

Examine your options before jumping into layoffs.

Workforce management requires simultaneous strategies. Layoffs are best used when you need to restructure or make permanent changes. In a temporary downturn, furloughs and in-company reassignments, underpinned by effective performance management, maybe a better option.

Dave Cote, who engineered the turnaround of Honeywell in the 2000s used furloughs rather than layoffs to reduce costs during the Great Recession. Cote’s intact workforce enabled him to continue product development, earning Honeywell a three-year total stock return between 2009 and 2012 of 75% — more than 20 points higher than GE, his nearest competitor. Cote didn’t hesitate to use mass layoffs when exiting underperforming businesses. He also made strategic hires in areas he was growing, and consistently used performance management to ensure that the people who worked in the company were the ones they wanted to keep.

Make fair decisions.

Research finds that the largest factor employees use to judge a layoff’s fairness is the reality of who is let go. Following straightforward criteria, like seniority or “last in, first out,” may make layoffs easier to explain, but realistically, it’s never that simple. You may want to keep some of your newest employees and not be bound to those who have been with you the longest.

Employee performance, while not the driving reason behind a layoff, is generally accepted as a plausible reason for selecting individuals to be let go, but ranking employees based on their relative performance is hard to do fairly. One laboratory study offered participants profiles of 25 employees and gave them performance evaluation ratings, absenteeism records, level of seniority, and data on whether they possessed skills that could transfer to another role in the company, as well as demographic data including employees’ sex, race, and age. Experts “found no support for performance playing a part in layoff decisions.” Instead, “personal characteristics of the employees are often used in making layoff decisions, despite the target employee’s experience, performance, and skill sets.”

Studies of post-layoff data find that companies can lose hard-won gains in their number of women and underrepresented employees through unintentional, unconscious bias that can lead managers to retain people who are like them. And this goes beyond demographics: A desire to retain the “best athlete” can also show up in higher incidents of layoffs among people with chronic health conditions and those who are on maternity leave. People who are perceived as difficult or are low on the list of a manager’s favorites, regardless of their performance, are more readily let go.

If you decide to move forward with a layoff, studies show three practices can help ensure fairness. First, make sure that you have budgeted enough time for deliberation. One study of HR executives found that they devoted less than an hour to each layoff candidate and as a result, they believed that at least 20% of people were wrongly terminated from the company. Second, consider using teams of managers, along with representatives of HR, to review layoff candidate lists for fairness. A third best practice is to develop a real-time tracker of the profiles of candidates who were being proposed to lose jobs. This allows for oversight and provides visibility at levels of departments, divisions, and the company as a whole.

Layoffs are as much about who is staying as who is being let go, and managers must be allowed to go to bat for people they want to retain while ensuring that the final list of layoff candidates is fair — on as many dimensions as possible.

Provide a soft landing.

In staff reductions, actions that are perceived as most fair by employees are also ones that give them choices, like voluntary buyouts with severance before layoffs, and support for multiple paths to re-employment. According to unpublished research conducted for Edelman’s 2022 Trust in the Workplace report, if you’re in the position of announcing layoffs, be prepared to use more creativity and spend a little more money than you might have before to provide a soft landing for employees.

Nokia got employees to stay for more than a year (some for as long as two years) after announcing a restructuring in 2011 by offering both paths to employment inside Nokia and support for finding jobs outside the firm. They also provided funding for individuals and small teams with credible plans to start their own businesses — 1,000 were developed — and provided a path to new skills by funding education. As a result, 60% of 18,000 employees from 13 countries, including the U.S., Finland, and India, knew what their next job was going to be before their job at Nokia ended. The company achieved the same percentage of sales for revenues from new products as they did before the announcement, and at €50 million (€ 2,800 per employee) the entire cost of the company-managed program was less than 4% of restructuring charges.

Don’t overlook the remaining staff.

Many employees jump ship following a layoff: One study found that a layoff affecting 1% of the workforce led to a 31% increase in the rate of voluntary turnover. Today’s robust job market provides ample alternatives for surviving employees who question the fairness of a layoff. Employees with low organizational commitment are 2.5 times more likely to leave a firm after a layoff occurred.

You’ll need to communicate a compelling case for why people should stay. Surviving and prospective employees want to hear three messages: We treated your colleagues well. We have a credible strategy to improve the company’s prospects. There is a clear role for you to play in the future success of the company. People trust in actions, not words, so the real test will be making sure that each of these statements syncs with things you have done and will keep doing.

Be prepared to publicly apologize.

In the past, corporate leadership refrained from making public apologies for reducing staff. Today, in contrast, the trend is for CEOs to apologize for eliminating jobs.

How you apologize for matters. When making a company apology, researchers have identified three essential elements for restoring lost trust: 1) Acknowledge harm and say you are sorry for it; 2) explain why you acted as you did, and 3) make an offer of repair that genuinely helps the person you harmed. Stripe CEO Patrick Collison’s recent email to employees in which he announced a 14% reduction of staff succinctly communicates an effective apology. Collison’s tone conveyed sincerity in acknowledging mistakes: “We’re very sorry to be taking this step and John and I are fully responsible … We overhired for the world we’re in.”

It’s hard for leaders to make this type of public apology without inviting cynicism, and today, social media and online news archives make it easy for anyone to find contradictions in a CEO’s message.

. . .

Successfully managing workforce changes within today’s landscape ultimately requires evaluating your actions against the backdrop of trust. Your company will weather the storm of layoffs more successfully if you can maintain trust with three groups who will determine your success in the future: employees you let go, employees, you retain, and employees who don’t yet work for you.

You have a great opportunity to be better at this than other companies. Keeping trust at the center of your decision-making can lead to surprising, beat-the-odds success, as the above examples from Honeywell and Nokia show. Centering trust also offers leaders a reminder: Your actions will have consequences that are more visible than they’ve been in the past and you will be judged as trustworthy — or not — based on them.