The Federal Reserve continued its campaign to raise interest rates Wednesday, but much of the focus was elsewhere: the impact of the banking crisis that has emerged in recent weeks.

Up until early March, expectations around this week’s Fed meeting lay squarely on the outlook for inflation and the stronger-than-expected pace of economic growth.

But with the collapse of Silicon Valley Bank SIVB and subsequent events, the equation for the Fed has changed dramatically.

Fed Likely to Sharply Cut Rates in 2024

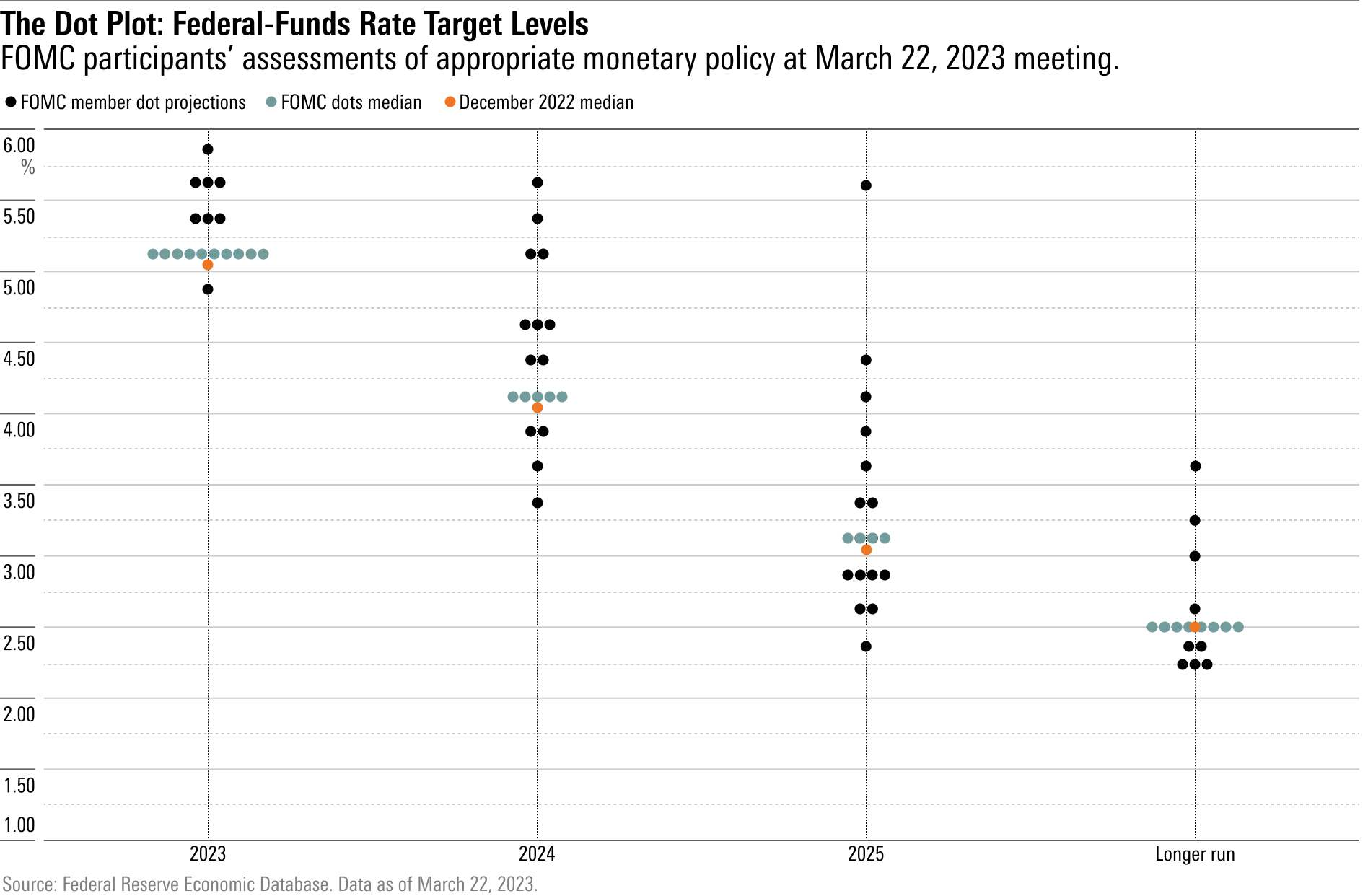

The Fed is now struggling to chart the best course forward as the U.S. economy seemingly sits on a knife edge between high inflation and financial crisis risk. The Fed is expecting to hold rates at a plateau of around 5% through the end of 2023, but we think that rates are likely to fall sharply after that.

The Fed pushed ahead with another 0.25-point increase in the federal funds rate to a target range of 4.75% to 5.00%, despite budding signs of distress in the U.S. financial system.

The majority of market participants had expected a 0.25-point increase before the meeting. However, some investors had bet on the Fed abstaining from a hike at this meeting in order to help stabilize the financial system.

Fears of a potential financial crisis have multiplied following the failure of Silicon Valley Bank on March 10, when the bank was put into receivership after a run on its deposits. With around $200 billion in assets, this was the second-largest failure of an FDIC-insured bank in U.S. history (next to Washington Mutual in 2008). On March 12, Signature Bank SBNY ($110 billion in assets) also failed. The fate of First Republic Bank FRC ($200 billion in assets) stands in jeopardy following a run on its deposits. Meanwhile, an abrupt liquidity crunch on Credit Suisse CS led to a rushed sale to UBS UBS, signaling a spread of financial turmoil to European markets.

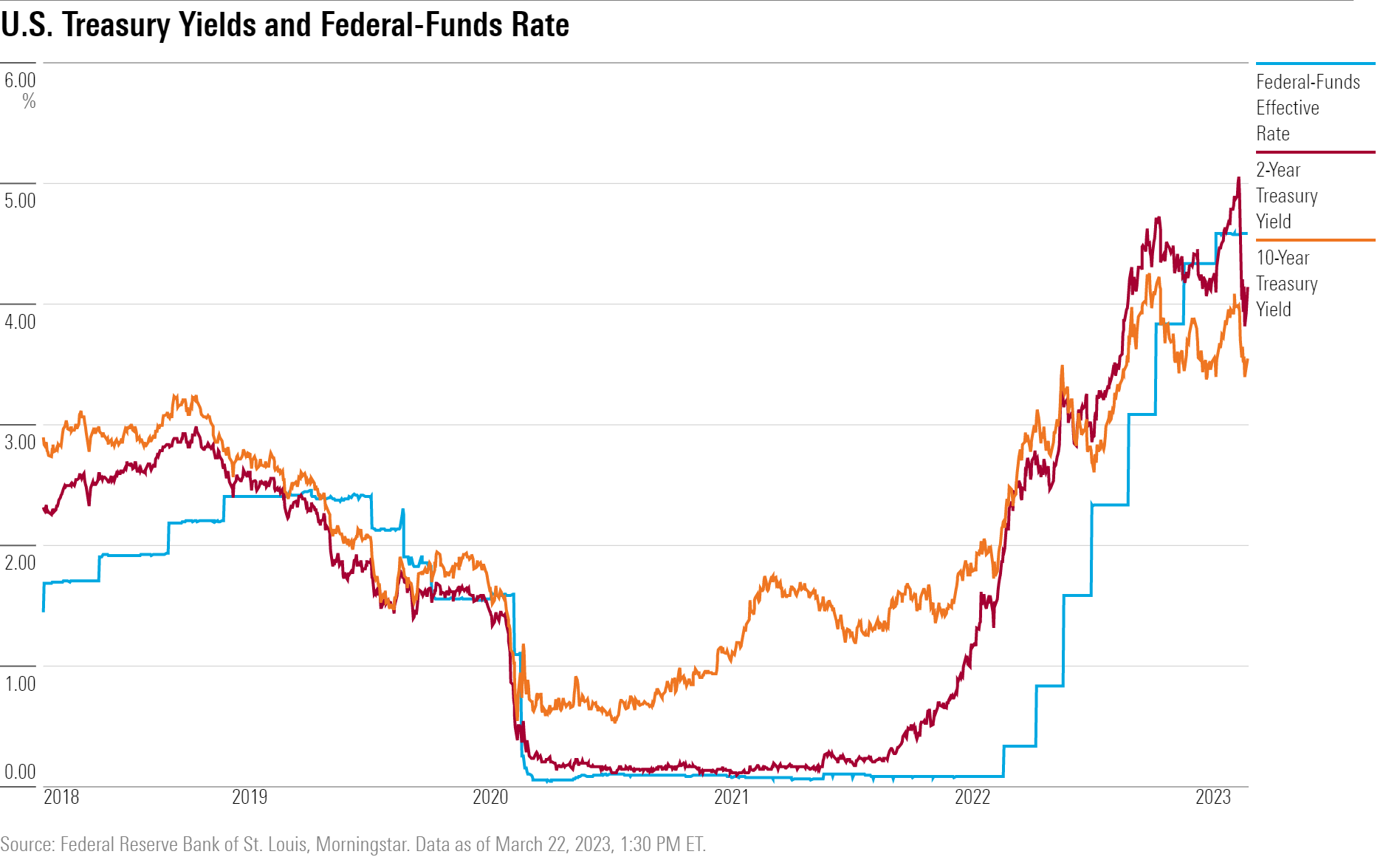

Fed Takes Rates to Highest Level Since 2007

With today’s hike, the federal funds rate reached a target range of 4.75 to 5.00%, the highest rate since 2007. Altogether, the Fed has increased the federal funds rate by 4.75 percentage points since March 2022. That’s the largest one-year increase since the 1980-81 hiking cycle when the Fed sought to tame the “Great Inflation” that raged throughout the 1970s.

The aggressive rate hikes of the early 1980s set in motion a cascade of bank failures over the course of that decade (referred to as the savings and loan crisis). In that episode, certain banks were highly exposed to interest-rate risk, meaning they would incur losses as interest rates rose. The banking industry learned from the savings and loan crisis to do a better job in hedging interest-rate risk, and today most banks look like they’re weathering the storm of rate hikes in decent shape. But a small minority of banks have failed to hedge interest-rate risk adequately, leading to the recent spate of distress.

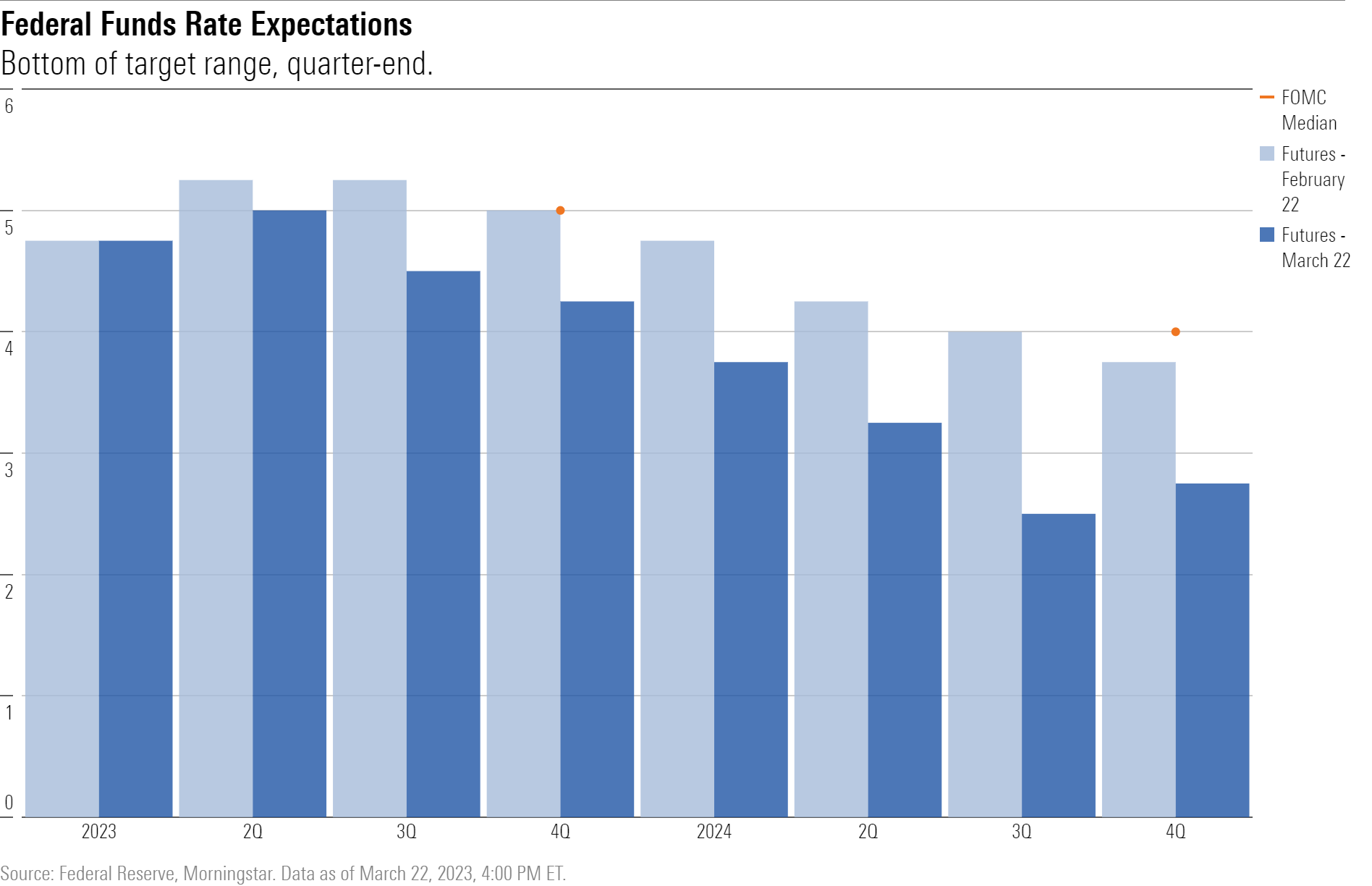

Although the market is now expecting multiple rate cuts before the end of 2024 to bring the federal-funds rate down to 4.25%, the Fed is expecting to hold rates firm at about 5.00%. The Fed believes that it can curb financial distress with tools other than cutting the federal funds rate, clearing the way for monetary policy to remain restrictive in order to continue to fight inflation.

To this end, the Fed has opened the spigots of funding for banks in need of liquidity, via the traditional discount window along with its new Bank Term Funding Program. Financial distress no longer appears to be worsening, and Fed Chair Jerome Powell mentioned that “deposit flows have stabilized in the last week.”

Markets Skeptical of Fed Forecasts

The market’s views on the path of the federal funds rate have shifted abruptly in response to the events of the past few weeks. The implied path for the federal-funds rate has fallen by nearly 100 basis points, and bond yields have fallen commensurately. Clearly, the market is baking in a much higher probability of recession and/or financial crisis risk. This means the market is more skeptical that the Fed can stabilize the financial system while keeping the federal-funds rate high.

Even if the Fed succeeds in preventing further bank failures, a key question is how much supply of bank lending will contract in the wake of recent events. Bank lending standards were already tightening in recent months, and this tightening will likely progress further as banks shift to a more conservative stance. This will help reduce business investment and hiring, along with consumer spending. But as Powell acknowledged, the degree of impact is highly uncertain.

For the near term (over the next two to three quarters), we tend to agree with the Fed’s view that the federal funds rate can remain high without triggering an explosion of financial distress. We also don’t take it as a given that bank troubles will massively weigh on economic growth. Hundreds of banks—albeit mostly very small ones—failed per year in the latter half of the 1980s, yet neither a financial crisis nor a recession occurred. Not every bank failure is a harbinger of a 2008-style collapse in the financial system.

Whatever the ultimate impact, it will likely take several quarters for tightening lending standards to affect business and consumer spending. Thus, the economy isn’t going to be immediately cooled off by financial distress, and hence neither will the inflation problem be immediately removed by recent developments. Core consumer price inflation averaged 5.2% annualized in the past three months. We do expect inflation to come down most of the way back to normal by the end of 2023. But forecasts of rate cuts starting this summer (as the market now expects) look premature.

As the Federal Reserve has consistently lifted its key interest rate over the past year, Americans have seen the effects on both sides of the household ledger: Savers benefit from higher yields, but borrowers pay more.

The Fed increased rates by a quarter-point on Wednesday as policymakers balanced what they see as the continuing need to tame inflation and recent turmoil in the banking industry.

Here’s how rising rates affect consumers.

Credit Cards

Credit card rates are closely linked to the Fed’s actions, so consumers with revolving debt can expect to see those rates rise, usually within one or two billing cycles. The average credit card rate was 20 percent as of March 15, according to Bankrate.com, up from around 16 percent in March last year, when the Fed began its series of rate increases.

Car Loans

Car loans tend to track the five-year Treasury note, which is influenced by the Fed’s key rate — but that’s not the only factor that determines how much you’ll pay.

A borrower’s credit history, the type of vehicle, loan term, and down payment are all baked into that rate calculation. The average interest rate on new-car loans was 6.95 percent in February, according to Edmunds, up about a percentage point from six months earlier.

Student Loans

Whether the rate increase will affect your student loan payments depends on the type of loan you have.

The rate for current federal student loan borrowers isn’t affected because those loans carry a fixed rate set by the government.

But new batches of federal loans are priced each July, based on the 10-year Treasury bond auction in May. Rates on those loans have already jumped: Borrowers with federal undergraduate loans disbursed after July 1 (and before July 1, 2023) will pay 4.99 percent, up from 3.73 percent for loans disbursed the year-earlier period.

Borrowers of private student loans should also expect to pay more: Both fixed- and variable-rate loans are linked to benchmarks that track the federal funds rate. Those increases usually show up within a month.

Mortgages

Rates on 30-year fixed mortgages don’t move in tandem with the Fed’s benchmark rate, but instead generally track the yield on 10-year Treasury bonds, which are influenced by a variety of factors, including expectations around inflation, the Fed’s actions and how investors react to all of it.

After climbing above 7 percent in November, for the first time since 2002, mortgage rates dipped close to 6 percent in February before drifting back up to 6.6 percent last week, according to Freddie Mac. The average rate for an identical loan was 4.2 percent the same week in 2022.

Other home loans are more closely tethered to the Fed’s move. Home equity lines of credit and adjustable-rate mortgages — which each carry variable interest rates — generally rise within two billing cycles after a change in the Fed’s rates.

Savings Vehicles

Savers seeking a better return on their money will have an easier time — yields have been rising, but not uniformly.

An increase in the Fed’s key rate often means banks will pay more interest on their deposits, though it doesn’t always happen right away. They tend to raise their rates when they want to bring more money in, and recent turmoil in the financial industry may push banks to raise rates to convince anxious depositors to keep money in their accounts.

Rates on certificates of deposit, which tend to track similarly dated Treasury securities, have been ticking higher. The average one-year C.D. at online banks was 4.6 percent at the start of March, up from 0.7 percent a year earlier, according to DepositAccounts.com.