Artificial intelligence (AI) recently gained new attention with the release of ChatGPT and Dall-E. These tools and the broader array of AI-driven business applications represent a new reality for workers.

Historically, changes in technology have often automated physical tasks, such as those performed on factory floors. But AI performs more like human brainpower and, as its reach grows, that has raised questions about its impact on professional and other office jobs – questions that the Pew Research Center seeks to address in a new analysis of government data.

What we found

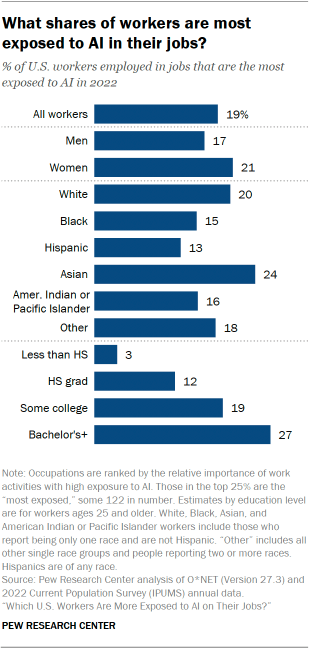

- In 2022, 19% of American workers were in jobs that are the most exposed to AI, in which the most important activities may be either replaced or assisted by AI.

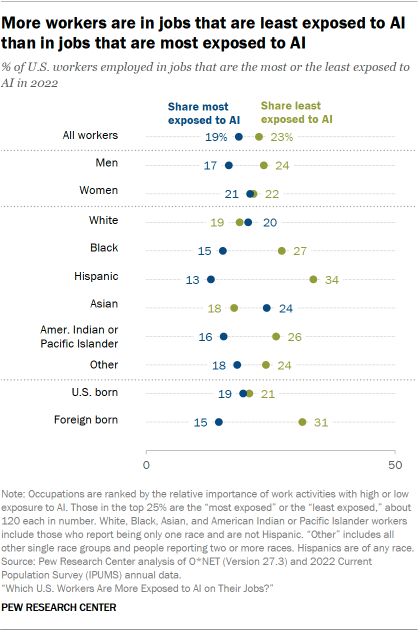

- 23% of workers have jobs that are the least exposed to AI, in which the most important activities are farther from the reach of AI. Other workers, nearly six in ten in all, are likely to have varying levels of exposure to AI.

- Jobs with a high level of exposure to AI tend to be in higher-paying fields where a college education and analytical skills can be a plus.

Certain groups of workers have higher levels of exposure to AI

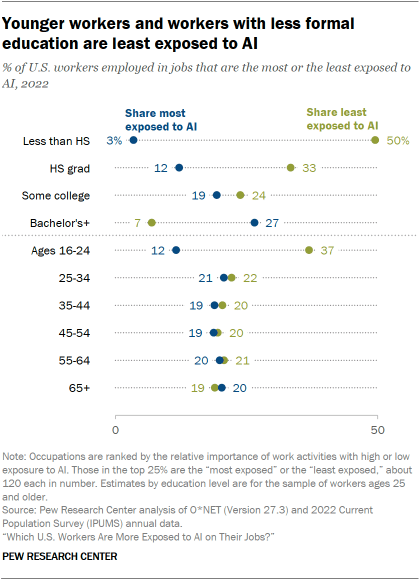

- Those with more education: Workers with a bachelor’s degree or more (27%) are more than twice as likely as those with a high school diploma only (12%) to see the most exposure.

- Women: A greater share of women (21%) than men (17%) are likely to see the most exposure to AI. This is because of differences in the types of jobs held by men and women.

- Asian and White: Asian (24%) and White (20%) workers are more exposed than Black (15%) and Hispanic (13%) workers.

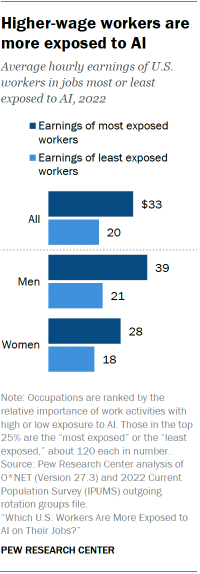

- Higher-wage workers: In 2022, workers in the most exposed jobs earned $33 per hour, on average, compared with $20 in jobs with the least amount of exposure.

Workers seem more hopeful than concerned about the impact of AI on their jobs

- A recent Pew Research Center survey finds that many U.S. workers in more exposed industries do not feel their jobs are at risk – they are more likely to say AI will help more than hurt them personally. For instance, 32% of workers in information and technology say AI will help more than hurt them personally, compared with 11% who say it will hurt more than it helps.

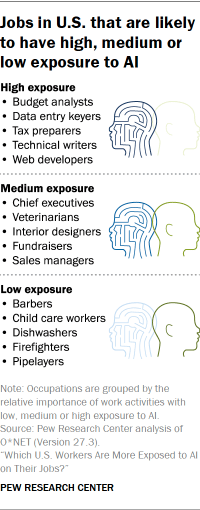

Which jobs are more exposed to AI? Work-related tasks vary in their exposure to AI. Some activities, such as repairing equipment, may have low exposure to AI, while others may have a medium or a high degree of exposure. Also, activities with different levels of exposure may be equally important within many jobs.

In our analysis, jobs are considered more exposed to artificial intelligence if AI can either perform their most important activities entirely or help with them.

For example, AI could replace, at least to a degree, the tasks “getting information” and “analyzing data or information,” or it could help with “working with computers.” These are also among the key tasks for judicial law clerks and web developers, and they are more exposed to AI than other workers. However, AI alone cannot “assist and care for others” or “perform general physical activities.” Thus, nannies – for whom these are essential activities – are less exposed to AI.

In our analysis, jobs that were placed in the top 25% when ranked by the importance of work activities with high exposure to AI were judged to be the most exposed. Jobs that are placed in the top 25% when ranked by the importance of work activities with low exposure to AI are the least exposed. The remaining jobs, such as chief executives, are likely to see a medium level of exposure to AI. (Refer to the appendix for an extended list of examples of occupations in each group.)

Will exposure to AI lead to job losses? The answer to this is unclear. Because AI could be used either to replace or complement what workers do, it is not known exactly which or how many jobs are in peril. For this reason, our study focuses on the level of exposure jobs have to AI. It sets aside the question of whether this exposure will lead to jobs lost or jobs gained.

Consider customer service agents. Evidence shows that AI could either replace them with more powerful chatbots or it could enhance their productivity. AI may also create new types of jobs for more skilled workers – much as the internet age generated new classes of jobs such as web developers. Another way AI-related developments might increase employment levels is by giving a boost to the economy by elevating productivity and creating more jobs overall.

Overall, AI is designed to mimic cognitive functions, and it is likely that higher-paying, white-collar jobs will see a fair amount of exposure to the technology. But our analysis doesn’t consider the role of AI-enabled machines or robots that may perform mechanical or physical tasks. Recent evidence suggests that industrial robots may reduce both employment and wages. Moreover, jobs held by low-wage workers, those without a high school diploma, and younger men are more exposed to the effects of industrial robots.

What data did we use? This analysis rests on data on the importance of 41 essential work activities in 873 occupations from the U.S. Department of Labor’s Occupational Information Network (O*NET, Version 27.3). We used our judgment to determine which of these activities have low, medium, or high exposure to AI, but focus on the importance of low- and high-exposure activities. For additional analysis, the 873 occupations were further grouped to a total of 485 for which government data on employment and earnings of workers were available. That allowed us to analyze the potential impact of AI on different groups of workers. Other findings about how workers feel about AI come from a Center survey of 11,004 U.S. adults conducted between Dec. 12 and 18, 2022. (Refer to the text boxes and methodology for more details.)

Our other key findings

- Most workers are more likely to work in jobs with less exposure to AI than in jobs with more exposure. This is true among men, Black and Hispanic workers, younger workers, and workers with less formal education, among others.

- Asian workers and college graduates are among the highest-paid workers most exposed to AI. The most exposed workers earn more than the least exposed workers no matter their demographic characteristics, and the gap is especially striking among men, Asian workers, and foreign-born workers.

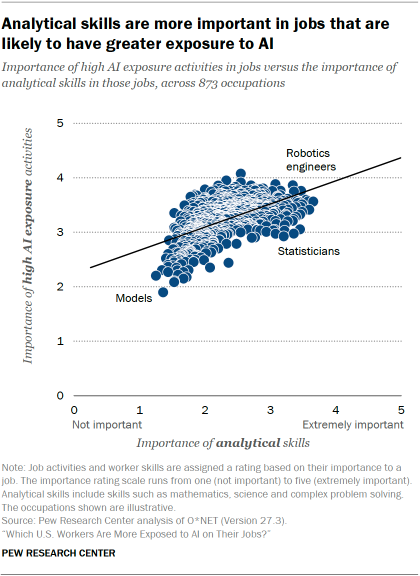

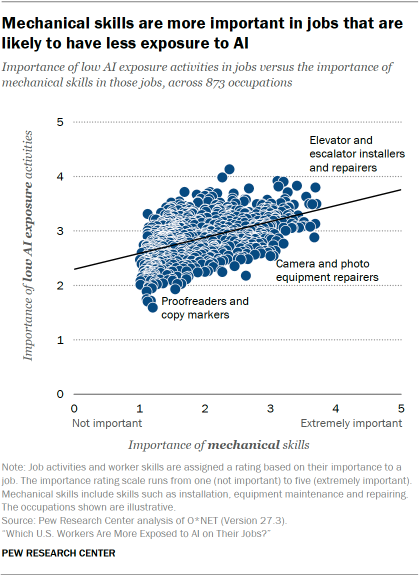

- Analytical skills are more important in jobs with more exposure to AI. These skills include critical thinking, writing, science, and mathematics. Mechanical skills, such as equipment maintenance, are more important in jobs with less exposure to AI.

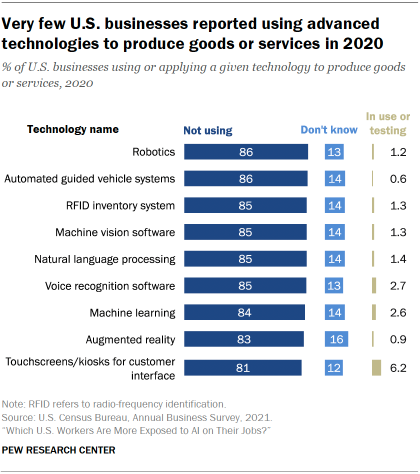

- Scarcely any U.S. businesses – fewer than 3% – reported using advanced technologies such as machine learning or machine vision software to produce goods or services in 2020, according to the most recent available data from the U.S. Census Bureau. Still, these were large businesses that accounted for about 11% to 16% of overall employment.

Sidebar: How we determined the degree to which jobs are exposed to artificial intelligence

In our analysis, we considered two major questions when assessing the exposure of jobs to AI:

- What is the likelihood that a work activity may be substituted for or complemented by AI at this time? Is the likelihood high, medium or low?

- How important are activities with high or low exposure to AI in any given job, relative to the importance of other activities?

Classifying work activities by exposure to AI

The O*NET database lists a set of 41 work activities in common across all occupations. Examples of these activities are getting information, selling or influencing others, and handling and moving objects (refer to the methodology for the complete list). We used our collective judgment to designate each activity as having high, medium, or low exposure to AI. Consensus on some activities, such as performing general physical activities or processing information, was reached quickly. The former is judged as having low exposure to AI and the latter is judged as having high exposure.

In other instances, we used additional details on a work activity to reach a consensus. The question we asked ourselves at this stage was the following:

Are most of the detailed tasks that comprise a work activity exposed to AI?

For example, the job activity “performing for or working directly with the public” is ambiguous on the surface. But consider the list of detailed tasks that comprise this broad activity:

- Audition for roles

- Perform for recordings

- Perform music for the public

- Collaborate with others to prepare or perform artistic productions

- Entertain the public with comedic or dramatic performances

- Perform dances

- Operate gaming equipment

- Conduct amusement or gaming activities

- Respond to customer problems or complaints

- Respond to customer inquiries

- Answer customer questions about goods or services

- Communicate with customers to resolve complaints or ensure satisfaction

- Resolve customer complaints or problems

- Correspond with customers to answer questions or resolve complaints

The consensus we reached was that most of these detailed tasks, such as interfacing with customers or creating music, had a high degree of exposure to AI. Only a few tasks – auditioning, comedic or dramatic performances, and dancing – were considered to have relatively low exposure to AI. For that reason, the broad activity “performing for or working directly with the public” is deemed to have high exposure to AI.

At the other end of the exposure, scale is the work activity “coaching and developing others,” entailing:

- Coach others

- Encourage patients during therapeutic activities

- Visit individuals in their homes to provide support or information

- Encourage students

- Interact with patients to build rapport or provide emotional support

- Support the professional development of others

- Encourage patients or clients to develop life skills

The focus of most of these detailed tasks involves personal interaction. So, we judged that the activity “coaching and developing others” has low exposure to AI.

Overall, 16 work activities were assessed to have high exposure to AI, 16 more were judged to have medium exposure, and nine were deemed to have low exposure. (Refer to the methodology for where each activity was classified.)

Determining the level of exposure of a job to AI

The 41 work activities listed in O*NET are spread across all occupations in the O*NET database. That is to say, each occupation is a mix of low, medium, and high AI-exposure activities. The question then is:

Which work activities are relatively more important in a job? Are high- or low-exposure activities more important than other activities?

To answer this, we first estimated the averages of the importance ratings for high-, medium- and low-exposure activities in each job, where the rating of each activity within a category is taken from the O*NET database. The rating for each activity ranges from one (not important) to five (extremely important).

Overall, among the 873 occupations we looked at, high-exposure activities were rated as being important to extremely important in 77% of occupations, and medium-exposure activities were similarly important in 72% of occupations. Low-exposure activities were rated as important in 39% of occupations. This suggests that high, medium, and low exposure could simultaneously be important in a job.

The final step was to estimate the relative importance of high-, medium- or low-exposure activities in each job – that is, to determine which tasks are more important than the others in any given job. This procedure is described in the methodology. Occupations were then ranked two ways, once by the relative importance of high-exposure work activities and again by the relative importance of low-exposure work activities.

In our analysis, jobs that are most exposed to AI are in the top 25% of occupations ranked by the relative importance of high-exposure activities. Jobs that are least exposed to AI are in the top 25% of occupations ranked by the relative importance of low-exposure work activities. The other jobs may be thought of as having a medium level of exposure to AI. (Refer to the appendix for examples of occupations that are among the most or least exposed or have a medium level of exposure.)

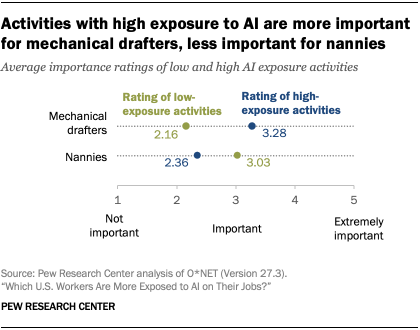

To take an example, consider mechanical drafters, who prepare detailed working diagrams of machinery and mechanical devices. Mechanical drafters are among the workers most exposed to AI. For them, high-exposure activities have an average rating of 3.28 but low-exposure activities have an average rating of 2.36, where a rating of 3 means an activity is important.

For nannies, among the least exposed workers, high-exposure activities have an average rating of 2.36 but low-exposure activities have a rating of 3.03.

Previous research on the impact of AI on U.S. workers

Our analysis follows in the footsteps of other researchers who have recently examined the impact of AI on the workplace. Eloundou, Manning, Mishkin, and Rock (March 2023) conclude that about one-in-five U.S. workers may see an impact on half or more of their job tasks. Felten, Raj, and Seamans (April 2021) find that white-collar occupations requiring advanced degrees are most exposed to AI, as are industries providing financial or legal services. Webb (January 2020) reports that high-skill occupations, highly educated and older workers will be more impacted by AI, but he does not draw conclusions about the nature or the extent of the impact on workers. Our findings are broadly consistent with the results of these analyses.

1. Exposure of workers to AI

Although artificial intelligence may appear to be everywhere all at once, workers overall are more likely to be in jobs that are the least exposed to AI than the most exposed. In 2022, nearly one-in-four U.S. workers (23%) were employed in the least exposed jobs, compared with one-in-five workers (19%) in the most exposed jobs, our analysis found.

This difference applies across most groups of workers, arising from differences in the types of jobs they do. For instance, men are more likely than women to work in jobs in which physical or manual tasks are performed, such as in construction, production, repair, and maintenance occupations. Our analysis shows that 24% of men worked in jobs that are least exposed to AI in 2022, while 17% were in the most exposed jobs. However, women are about equally likely to work in jobs that are the most or the least exposed to AI.

Black, Hispanic, and American Indian or Pacific Islander workers are more likely than other racial and ethnic groups to be employed in the least exposed jobs by large margins. For instance, only 13% of Hispanic workers are in jobs that are the most exposed to AI, compared with 34% who are in the least exposed jobs. Black and American Indian or Pacific Islander workers are more likely to be employed in the least exposed jobs by a margin of about 10 percentage points each. Asian workers, who are more likely than average to work in professional and technical occupations, are a notable exception: Their share in the most exposed jobs exceeds the share in the least exposed jobs by a margin of 6 points.

The share of foreign-born workers in the least exposed jobs is about double the share in the most exposed jobs – 31% vs. 15%. This is perhaps because about half of the foreign-born workers in the U.S. are Hispanic, and foreign-born workers overall are more likely to work in construction, maintenance occupations, and production occupations.

Half of workers without a high school diploma and a third of those with a high school diploma only hold jobs with the least exposure to AI. Workers with these levels of education comprised about 31% of the U.S. labor force ages 25 and older in 2022. But only 7% of workers with a bachelor’s degree or higher level of education – 44% of the U.S. workforce 25 and older – are in the least exposed jobs.

Except for those ages 16 to 24, about one-in-five workers in all age groups are likely to see either a high or a low degree of exposure to AI. The youngest workers are about three times as likely to work in the least exposed jobs as in the most exposed jobs – 37% vs. 12%.

A handful of occupations account for large shares of men and women who have high exposure to AI

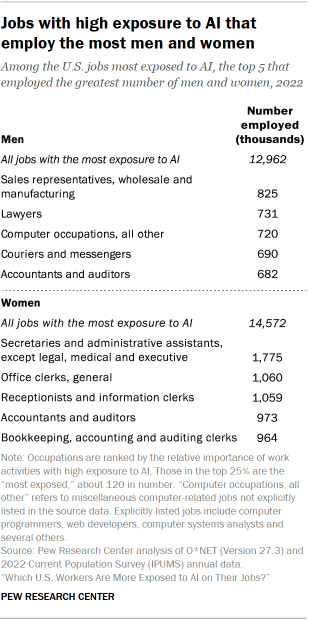

Overall, nearly 13 million men and 14.6 million women were employed in 2022 in occupations that have the most exposure to AI. Among these occupations, some 825,000 men worked as sales representatives alone. The top five jobs for men among the most exposed occupations accounted for a total of 3.6 million jobs for them, representing 28% of all men facing the greatest exposure to AI.

This concentration is even more pronounced for women. Some 5.8 million women who face the most exposure to AI in their jobs were employed in just five occupations, representing 40% of the total. These jobs are largely administrative in nature, with accounting and auditing jobs exposing large numbers of both men and women to AI.

2. Earnings of workers with more, or less, exposure to AI

In 2022, the average hourly earnings of workers in the jobs most exposed to artificial intelligence stood at $33, compared with $20 in jobs with the least amount of exposure. Men working in high-exposure jobs earned $39 per hour, much greater than the earnings of men in the least exposed jobs. Women in high-exposure jobs made $28 per hour, also notably more than what the least exposed women earned, according to our analysis. (Dollar amounts are expressed in 2022 prices.)

Workers in jobs most exposed to AI also earn more than workers likely to see a medium level of exposure. These workers, in jobs neither the most nor the least exposed to AI, earned $30 per hour, on average. Men in these jobs made $31 per hour, but women earned $29 per hour, about the same as women most exposed to AI.

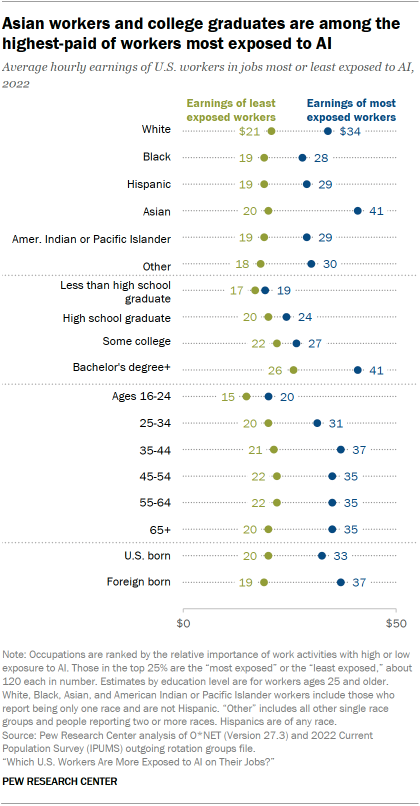

Asian workers and college graduates are among the highest paid of workers most exposed to AI

Looking at other groups of workers, the average hourly earnings of workers in the jobs most exposed to AI ranged from $19 for those without a high school diploma to $41 for Asian workers and college graduates in 2022. In part, this is because not all groups of workers have the same jobs within the broader set of occupations most exposed to AI. For instance, Asian workers represent 8% of employment in the most exposed occupations, but they account for about a third of all computer hardware engineers. Similarly, college graduates are more likely than average to be aerospace engineers or in similar jobs.

No matter their demographic characteristic, the most exposed workers earn more than the least exposed workers. Among racial and ethnic groups, Asian workers employed in the most exposed jobs earned about twice as much as Asian workers in the least exposed jobs – $41 vs. $20.

Across education levels, the largest gap in earnings surfaces among those with college degrees. The most exposed college graduates earned $41 per hour in 2022 and the least exposed earned $26 per hour. A gap of about $11 to $16 per hour prevails among all workers ages 25 and older.

Foreign-born workers who are most exposed to AI are also among the higher-paid workers, making $37 per hour in 2022. This was about double the earnings of foreign-born workers who are the least exposed ($19). The earnings gap among U.S.-born workers is less pronounced but still large.

Most groups of workers in the most exposed jobs also typically earn about as much as or more than workers in jobs with a medium level of exposure to AI. For instance, Asian workers in the most exposed jobs earned $41 per hour, compared with $35 per hour among Asian workers in jobs with a medium level of exposure. Several other groups of workers in the most exposed jobs earned about $2 to $4 more per hour than workers in jobs with more mid-level exposure to AI. (Refer to the appendix for the full set of estimates.)

3. Workers’ views on the risk of AI to their jobs

One reason artificial intelligence will penetrate more deeply into some sectors of the U.S. economy than others is that the mix of jobs varies across industries.

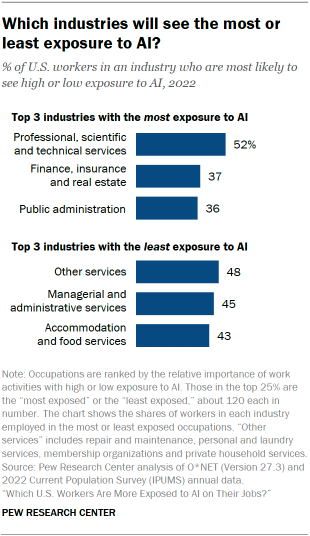

We found in our analysis that about half of workers (52%) in the professional, scientific, and technical services sectors face a high degree of exposure to AI, more than double the rate for workers overall. Exposure is also much greater than average for workers in finance, insurance, and real estate (37%) and public administration (36%).

At the other end of the spectrum, about half of workers (48%) in the other services sector, including repair, maintenance, and personal and household services, are likely to experience little exposure to AI. More than four-in-ten workers in managerial and administrative services (45%) and accommodation and food services (43%) should see relatively minimal exposure to AI. These are sectors in which workers, like nannies, are more likely to engage in physical or social tasks. (The appendix provides a complete list of industries and their exposure to AI.)

Workers in more exposed industries see less risk to their jobs from AI

A recent Pew Research Center survey shows that many workers who are likely to see more exposure to AI do not necessarily feel their jobs are at risk. In particular, U.S. adults working in the most exposed industries are less concerned about the impact of AI on them personally.

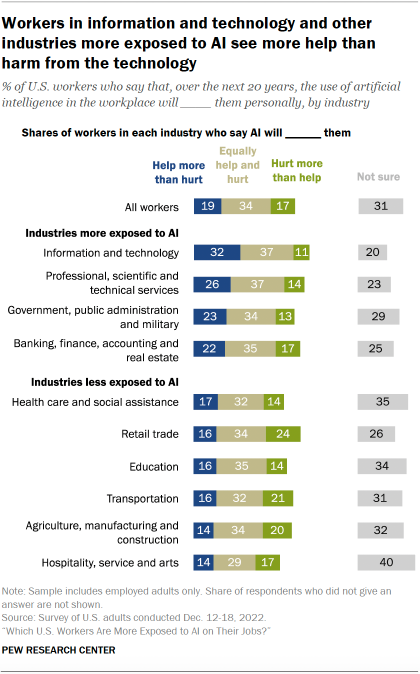

In the survey, 16% of all U.S. adults said they think AI will help more than hurt them personally over the next 20 years, and 15% said they thought AI would hurt more than help. But workers in different industries had notably different views on this question. Our new analysis shows that about one-third (32%) of workers in the information and technology sector said that AI will help more than hurt them personally. Another 37% said AI will equally help and hurt, and only 11% said it will hurt more than help.

Additionally, about one-in-four workers in professional, scientific, and technical services (26%) said AI will help more than hurt, and 23% in government, public administration, and the military said the same.

In contrast, relatively few workers in hospitality, services, and arts (14%) think AI will help more than hurt them personally. Four-in-ten workers in this sector are not sure about AI’s potential impact on them, which is among the higher shares across industries. There is a similar variance in the opinion of workers across industries about whether the use of AI in the workplace will help or hurt the U.S. economy (these estimates are in the appendix).

In a recent report based on our survey, we also found that many groups expected to be more exposed to AI are more optimistic about its impact on them. Notably, Asian adults, college graduates, and upper-income workers were more likely than other workers to say they think the use of AI in the workplace over the next 20 years will help more than hurt them personally at the workplace. Women were half as likely as men – 11% vs. 22% – to say this, but they were also more likely than men to say they were not sure of AI’s potential impact on them personally.

4. Skills needed in high- and low-exposure jobs

In addition to the work activities they must perform, workers can also be classified by the skills they are required to have in order to perform their jobs. The O*NET database lists a total of 35 key skills, such as critical thinking, writing, science, negotiation, time management, and repair. In this analysis, we grouped these skills into five major skill families: social, fundamental, analytical, managerial, and mechanical (refer to the text box for definitions of different skill groups). Then we looked at how these different job skills map with our assessment of how exposed different jobs are to artificial intelligence.

Our analysis shows that analytical skills, such as science, mathematics, and programming, are more important in jobs that have high exposure to AI. In contrast, mechanical skills are more important in jobs with lower exposure to AI. The nature of these relationships is apparent from the charts that plot the importance of these skills and work activities across the 873 occupations we studied: The need for one rises with the need for the other.

Looking at the relationship between the importance of high AI exposure activities and analytical skills, jobs such as robotics engineers appear at the top right of the plot. For these engineers, analytical skills have an importance rating of 3.47, and high AI exposure activities have an importance rating of 3.76, both falling between “important” and “very important” in O*NET terminology.

Jobs in which analytical skills are not important and AI exposure is limited appear on the bottom left. For example, consider models, including fashion models or those who pose for artists or photographers. For them, analytical skills have an importance rating of 1.36, and high AI exposure activities have an importance rating of 1.90, both lying between “not important” and “somewhat important.”

On the other hand, mechanical skills, such as repairing and installation, are more important in jobs in which low AI exposure skills are more important. For elevator and escalator installers and repairers, who appear at the top right, mechanical skills have an importance rating of 3.69 and low AI exposure activities have an importance rating of 3.80, both between “important” and “very important.”

For proofreaders and copy markers, mechanical skills have an importance rating of 1.17 and low AI exposure activities have an importance rating of 1.72, between “not important” and “somewhat important.”

Relatedly, among the workers employed in jobs most exposed to AI, about six-in-ten (59%) have jobs in which fundamental skills like critical thinking are most important. Nearly half (48%) work in jobs in which analytical skills are most important. Smaller shares have jobs in which managerial (34%) or social (26%) skills are more important, and very few (2%) are employed in jobs in which mechanical skills are most important.

5. Use of AI-related technologies by U.S. businesses

Because of the newness of technology, not much is known about the use of artificial intelligence in the business world. The most recent data collected by the government pertains to 2020, and AI systems have grown dramatically since then. While some policymakers are moving to create the ground rules for artificial intelligence, it is a rapidly evolving technology for which the speed of deployment and the purposes of adoption are hard to track in real-time.

The early reading suggests that AI has some distance to travel before its adoption is on par with other computer-based technologies. The 2020 data collected in the Census Bureau’s Annual Business Survey shows that the use of advanced computer-based technologies than was scarce among U.S. businesses. About nine-in-ten businesses or more reported that they were either not using or did not know if they were using AI-related technologies such as natural language processing, machine learning, machine vision software, or augmented reality to produce goods or services.

With the exception of touchscreens and kiosks for customer interface, only about 1% to 3% of businesses said they were using or testing any of the technologies to supply goods or services.

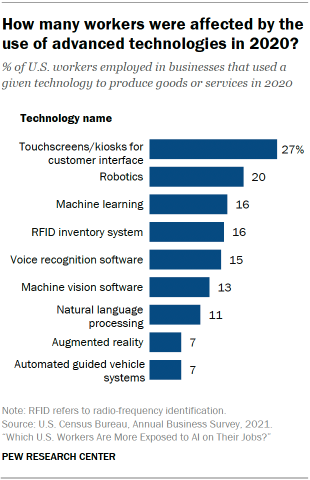

Nonetheless, the businesses that were using or testing technology had a much larger footprint in the labor market. Notably, while only about 1% of firms were using or testing robotics, those companies accounted for 20% of U.S. employment in 2020. Firms applying machine learning, machine vision, or natural language processing accounted for about 11% to 16% of employment. The use of touchscreens and kiosks for customer interface affected firms employing 27% of all workers.

These estimates show that the adoption of advanced technologies at the time was led by large businesses, and their decisions related to the use of AI affected a larger share of workers.

More direct evidence of the business use of AI comes from the Annual Business Survey conducted in 2019, which collected data for 2018. That survey found that about 3% of firms were using AI and 2% were using robotics. This lagged well behind the use of technologies such as specialized software (38%), cloud computing (32%), and dedicated equipment (18%). But firms using AI or robotics accounted for about 13% and 15% of U.S. employment, respectively.

The share of firms using AI was higher in the information sector, the professional, scientific, and technical services sectors, and the finance and insurance sector. This is consistent with the analysis in this report, which finds that these sectors are among the top four in terms of the share of their workforce that is most exposed to AI.