(Reuters) - Charles Munger, who died on Tuesday, went from working for Warren Buffett's grandfather for 20 cents an hour during the Great Depression to spending more than four decades as Buffett's second-in-command and foil atop Berkshire Hathaway Inc.

Munger's family had advised that he died peacefully on Tuesday morning at a California hospital, said Berkshire.

The union of Munger with Buffett is among the most successful in the history of business; they transformed Omaha, Nebraska-based Berkshire into a multi-billion dollar conglomerate with dozens of business units.

Yet the partnership that formally began when they teamed up in 1975 at Berkshire, where Buffett was chairman and Munger became vice chairman in 1978, thrived despite pronounced differences in style, and even investing.

Known almost universally as Charlie, Munger displayed a blunter form of musings, often in laconic one-liners, on investing, the economy, and the foibles of human nature.

He likened bankers to uncontrollable "heroin addicts," called the virtual currency Bitcoin "rat poison," and told CNBC that "gold is a great thing to sew into your garments if you're a Jewish family in Vienna in 1939 but I think civilized people don't buy gold. They invest in productive businesses."

Munger was no less pithy in talking about Berkshire, which made both he and Buffett billionaires and many early shareholders rich as well.

"I think part of the popularity of Berkshire Hathaway is that we look like people who have found a trick," Munger said in 2010. "It's not brilliance. It's just avoiding stupidity."

EXPANDING BUFFETT'S HORIZONS

Munger and Buffett did differ politically, with Munger being a Republican and Buffett a Democrat.

They also differed in personal interests.

For example, Munger had a passion for architecture, designing buildings such as a huge proposed residence for the University of California, Santa Barbara known as "Dormzilla," while Buffett claimed not to know the color of his bedroom wallpaper.

Yet at Berkshire, the men became inseparable, finishing each other's ideas and according to Buffett never having an argument.

Indeed, when Munger and Buffett would field shareholder questions for five hours at Berkshire's annual meetings, Munger routinely deadpanned after Buffett finished an answer: "I have nothing to add."

More often, he did, prompting applause, laughter, or both.

"I'm slightly less optimistic than Warren is," Munger said at the 2023 annual meeting, prompting laughter after Buffett expressed his familiar optimism for America's future. "I think the best road ahead to human happiness is to expect less."

Like Buffett, Munger was a fan of the famed economist Benjamin Graham.

Yet Buffett has credited Munger with pushing him to focus at Berkshire on buying wonderful companies at fair prices, rather than fair companies at wonderful prices.

"Charlie shoved me in the direction of not just buying bargains, as Ben Graham had taught me," Buffett has said. "It was the power of Charlie's mind. He expanded my horizons."

ORACLE OF PASADENA

Fans dubbed Buffett the "Oracle of Omaha," but Munger was held in equal esteem by his own followers, who branded him the "Oracle of Pasadena" after his adopted hometown in California.

Munger reserved many of his public comments for annual meetings of Berkshire; his investment vehicle Wesco Financial Corp, which Berkshire bought out in 2011; and Daily Journal Corp, a publishing company he chaired for 45 years.

To fans, Munger was as much the world-weary psychiatrist as a famed investor. Many of his observations were collected in a book, "Poor Charlie's Almanack: The Wit and Wisdom of Charles T. Munger," with a foreword by Buffett.

"I was raised by people who thought it was a moral duty to be as rational as you could possibly make yourself," Munger told Daily Journal shareholders in 2020.

"That notion," he added, "has served me enormously well."

In 2009, during the worst U.S. recession since the Great Depression, he tried to put his followers at ease.

"If you wait until the economy is working properly to buy stocks, it's almost certainly too late," he said at Wesco's annual meeting.

After that gathering, Los Angeles Times columnist and Wesco investor Kathy Kristof wrote about Munger: "He gives us hope."

TETE-A-TETE

Born on Jan. 1, 1924, Munger as a boy once worked part-time at the Omaha grocery run by Buffett's grandfather Ernest.

Buffett also worked there though he and Munger, who was 6-1/2 years older, did not work together.

Munger later enrolled at the University of Michigan but dropped out to work as a meteorologist in the U.S. Army Air Corps during World War II.

Despite never getting an undergraduate degree, Munger graduated from Harvard Law School in 1948.

He then practiced law in Los Angeles, co-founding the law firm now known as Munger, Tolles & Olson, before turning in the mid-1960s to managing investments in stocks and real estate.

Munger was a success, easily outperforming the broader market between 1962 and 1975 at his investment partnership Wheeler, Munger & Co.

According to Buffett biographer Alice Schroeder, Munger met Buffett in Omaha in 1959, where at a private room at the Omaha Club they "fell into a tete-a-tete" after being introduced.

More conversations followed, and they were soon talking by phone for hours on end.

"Why are you paying so much attention to him?" Munger's second wife Nancy reportedly asked her husband.

"You don't understand," Munger replied. "That is no ordinary human being."

KNOWING HIS MILIEU

The two shared the "value investing" philosophy espoused by Graham, looking for well-run companies with undervalued share prices.

Sometimes Munger and Buffett deemed those companies "cigar butts," meaning they were out of favor but had a few "puffs" of life left, but they often proved worth holding onto for decades.

Both generally shunned technology companies and other businesses they claimed not to understand, and they avoided getting burned after the late 1990s dot-com bubble went bust.

Instead, they oversaw purchases such as the BNSF railroad in 2010, and ketchup maker H.J. Heinz Co, which Berkshire and private equity firm 3G Capital bought in 2013. Berkshire and 3G later merged Heinz with Kraft Foods.

It was Munger who suggested that Buffett make one of Berkshire's few non-U.S. investments, in Chinese automobile and battery company BYD Co.

Munger was also responsible for introducing Buffett to Todd Combs, who along with Ted Weschler ran parts of Berkshire's investment portfolio.

Unlike Buffett, who opened a Twitter account - seldom used - Munger resisted heading into social media.

"That's not my milieu. I don't like too many things going on at once," he once told Reuters.

But in many other ways, he was much like his business partner, especially in not chasing the latest trends.

"I am personally skeptical of some of the hype that has gone into artificial intelligence," Munger said at the 2023 annual meeting. "I think old-fashioned intelligence works pretty well."

Munger lived modestly and drove his own car, though he used a wheelchair in his final years.

He was also a generous philanthropist, pledging more than $100 million in 2013 to build housing at the University of Michigan.

Nancy Munger died in 2010. Charlie Munger had six children and two stepchildren from his marriages.

Warren Buffett's trusted confidante Charlie Munger died on Tuesday at age 99, leaving a void at Berkshire Hathaway (BRKa.N) that investors said would be impossible to fill despite the conglomerate's well-established succession plan.

Berkshire said Munger died peacefully at a hospital in California, where he lived. No cause was given. Munger would have turned 100 on Jan. 1.

"Berkshire Hathaway could not have been built to its present status without Charlie's inspiration, wisdom, and participation," Buffett, Berkshire's 93-year-old chairman and chief executive, said in a statement.

The death of Munger, a Berkshire vice chairman since 1978, marks the end of an era in corporate America and investing.

Alongside Buffett, Munger was respected and adored by investors around the world, many of whom flocked to Berkshire's annual shareholder weekends in Omaha, Nebraska, to hear the duo’s folksy wisdom on investing and life.

Though Munger was not involved in Berkshire's day-to-day operations, his death leaves Buffett without his longtime sounding board.

Investors also said that while Berkshire has installed managers it could trust to keep the company going, Munger's loss would be deeply felt, and it prompted an outpouring of sorrow.

"It's a shock," said Thomas Russo, a partner at Gardner Russo & Quinn in Lancaster, Pennsylvania, and longtime Berkshire shareholder. "It will leave a big void for investors who have modeled their thoughts, words, and activities around Munger and his insights."

PHILOSOPHICALLY ALIKE

Since becoming a Berkshire vice chairman, Munger worked closely with Buffett on allocating Berkshire's capital and not mincing words when he thought his business partner was making a mistake.

"He was certainly one of the greatest investors, as a team with Buffett," said Rick Meckler, partner at Cherry Lane Investments in New Jersey. "I'm sure it is an enormous loss for Buffett personally."

Munger was known for steering Buffett away from purchasing what Buffett called "cigar butts" — mediocre companies that had a puff of smoke left and could be bought for very cheap prices — and instead favoring quality.

"Charlie felt that buying very good businesses at fair prices that could keep compounding and reinvesting cash flow into continued growth was more consistent with how he and Warren were philosophically and liked to invest," said Paul Lountzis, president of Lountzis Asset Management in Wyomissing, Pennsylvania. "They liked to own businesses forever."

Money manager Whitney Tilson, who knew Munger personally, said a "generation of investment managers" learned some of their craft from Munger and Buffett.

"What really glued us to these men was their advice on living a full life by instructing people how to think clearly, to be honest with oneself, to learn from mistakes, and to avoid calamities," he said.

Tilson said he attended dozens of meetings the men ran and that Munger once quipped to a private audience: "All I want to know is where I'm going to die so that I never go there."

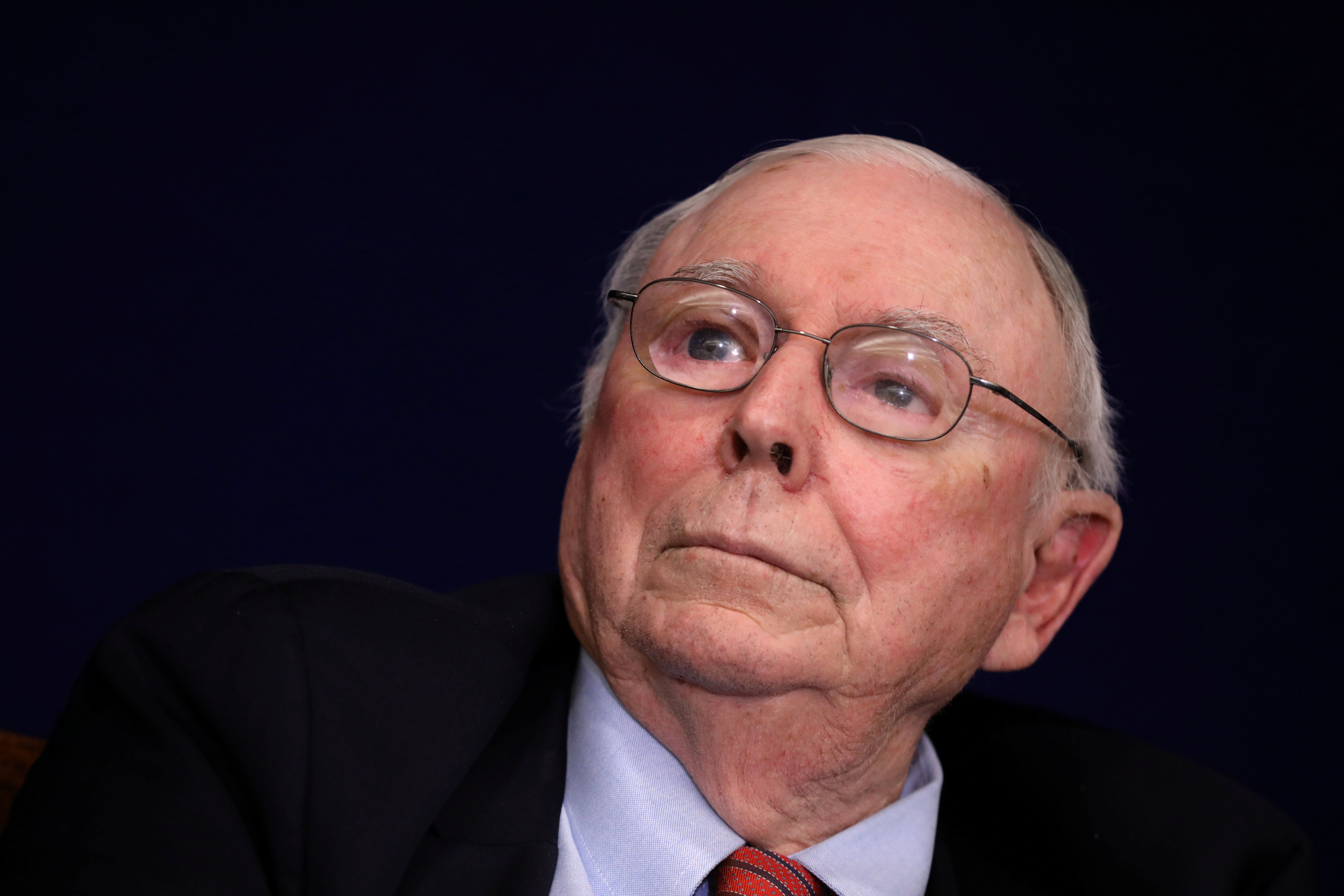

[1/3]Berkshire Hathaway Inc Vice Chairman Charles Munger speaks at the Daily Journal annual meeting in Los Angeles, U.S., February 15, 2017. REUTERS/Lucy Nicholson/File Photo Acquire Licensing Rights

BERKSHIRE'S FUTURE

Berkshire is unlikely to replace Munger and has not publicly discussed any need or desire to do so.

Two other vice chairmen, Greg Abel and Ajit Jain, have day-to-day oversight of Berkshire's non-insurance and insurance businesses, respectively.

Munger's death comes one week after Buffett donated about $866 million of Berkshire stock to four family charities and issued a rare shareholder letter acknowledging that his own time was finite, in the twilight of his own storied investing career.

In last week's letter, Buffett said Berkshire was "built to last" and would remain in good hands without him.

He has never publicly signaled a desire to step down, including after a prostate cancer diagnosis in 2012.

"At 93, I feel good but fully realize I am playing in extra innings," Buffett wrote.

Under Berkshire's succession plan, which Munger inadvertently mentioned at Berkshire's 2021 annual meeting, Abel would become chief executive once Buffett is no longer in charge.

Buffett's son Howard would become non-executive chairman, and one or two portfolio managers would take over investments.

Berkshire's businesses include the BNSF railroad, car insurer Geico, and an array of energy, industrial, and retail operations, as well as familiar consumer names such as Dairy Queen, Duracell, Fruit of the Loom, and See's Candies.

It also owns hundreds of billions of dollars of stocks, led by Apple (AAPL.O).

CHANGES WITHOUT CHARLIE

Perhaps the most noticeable change to the public from Munger's death will be Berkshire's annual weekend, which draws tens of thousands of people to Omaha and is live-streamed worldwide.

No longer will Munger be there to share the stage with Buffett and answer dozens of shareholder questions over five hours?

Abel and Jain, who have answered some of those questions in recent years, may play more of a role.

"The annual meeting will never be the same without Charlie's terse, open and honest comments," Lountzis said. "He was so different from Warren, in the sense that Charlie said what he thought and didn't give a damn what anyone else thought."

Russo added: "Berkshire may be a little less fun without him."

Warren Buffett, the billionaire investor, has had some advice for college students who want a fulfilling career: Don't think about the money.

In an annual letter to shareholders from 2021, Berkshire Hathaway's chairman and CEO discussed his continued enjoyment of his work. He referred to his regular talks with university students.

"I have urged that they seek employment in (1) the field and (2) with the kind of people they would select if they had no need for money," Buffett wrote.

Although he conceded that "economic realities may interfere with this kind of search," he urged students "to never give up on the quest."

"When they find that sort of job, they will no longer be 'working,'" Buffett said.

Buffett, 93, took control of Berkshire Hathaway in 1965. Together with his long-term business partner and confidant Charlie Munger, who died at age 99 on Tuesday, he's grown what was a struggling textile mill into a holding company with a market capitalization of more than $784 billion.

It holds significant shares in firms including Apple and the Coca-Cola Company and owns outright the BNSF Railway and Geico insurance company, among other major holdings.

"At Berkshire, we found what we love to do," Buffett writes. "With very few exceptions, we have now "worked" for many decades with people whom we like and trust."

Teaching helps Buffett to 'clarify his thoughts'

Buffett has offered similar advice in the past.

In a 2020 address to graduates of the University of Nebraska-Lincoln, his alma mater, he told students about the importance of finding a fulfilling career.

"I've been lucky enough to have one like that and I can tell you there's just nothing like that. It isn't work anymore, it's actually something you look forward to every day. You won't necessarily find it the day you get out, but it is out there," he said.

Students should also polish their communication skills and read lots, he advised.

Buffett started his first investing class 70 years ago and continued to work with students of all ages until 2018, he said in his letter.

"Teaching, like writing, has helped me develop and clarify my own thoughts," Buffett wrote, adding that this was a phenomenon Munger called the orangutan effect.

"If you sit down with an orangutan and carefully explain to it one of your cherished ideas, you may leave behind a puzzled primate, but will yourself exit thinking more clearly."

As for Munger, he said at the most recent Berkshire Hathaway annual meeting in Omaha that a key lesson in life is cutting out toxic people.

Well-known investor Charlie Munger has died at the age of 99 after a decades-long career.

Up until his death on Tuesday, Munger was at the helm of Berkshire Hathaway alongside Warren Buffett as the company's vice chairman.

Buffett and Munger shared the hometown of Omaha, and the pair led Berkshire into success spanning generations. Along the way, the billionaire business partners gave their critical, wise, and snappy opinions to young investors striving for their legendary status.

Over the years, Munger has sold or donated more than 75% of his shares in Berkshire Hathaway. Today, Munger's net worth is estimated at about $2.6 billion, according to Forbes. Had he kept his stock he could've been worth over $10 billion.

"I'm deliberately taking my net worth down," he told The Omaha World-Herald in 2013. "My thinking is, I'm not immortal, and I won't need it where I'm going."

Here are some of the best advice quotes that have been attributed to Munger.

"When you know you have an edge, you should bet heavily. They don't teach most people that in business school. It's insane. Of course, you've got to bet heavily on your best bets."

"The great lesson of life is get them the hell out of your life — and do it fast," Munger said about toxic people.

"There are maybe five, six times in a lifetime when you know you're right, you know you have one that's really going to work wonderfully, and you get a chance to do it. People who do it two or three times early, they all go broke because they think it's easy. In fact, it's very hard and rare."

"In my whole life, I have known no wise people who didn't read all the time — none, zero."

"The first rule is that you can't really know anything if you just remember isolated facts and try and bang 'em back."

"Almost everybody that has an unusually good result has three things: They're very intelligent, they worked very hard, and they were very lucky. It takes all three to get them on this list of the super-successful. How can you arrange to have two or three episodes of good luck? The answer is you can start early and keep trying a long time, and maybe you'll get one or two."

"The game of life is the game of everlasting learning. At least it is if you want to win."

"What do you want to avoid? Such an easy answer: sloth and unreliability. If you're unreliable, it doesn't matter what your virtues are. You're going to crater immediately. Doing what you have faithfully engaged to do should be an automatic part of your conduct. You want to avoid sloth and unreliability."

"The big money is not in the buying and selling, but in the waiting."

"Spend each day trying to be a little wiser than you were when you woke up."

"The best thing a human being can do is to help another human being know more."

"Invest in a business any fool can run, because someday a fool will. If it won't stand a little mismanagement, it's not much of a business. We're not looking for mismanagement, even if we can withstand it."

"Obviously if you want to get good at something which is competitive, you have to think about it and practice a lot. You have to keep learning because [the] world keeps changing and competitors keep learning. You have to go to bed wiser than you got up. As you try to master what you are trying to do — people who do that almost never fail utterly. Very few have ever failed with that approach. You may rise slowly, but you are sure to rise."

"You don't have a lot of envy."

"You don't have a lot of resentment."

"You don't overspend your income."

"You stay cheerful in spite of your troubles."

"You deal with reliable people."

"And you do what you're supposed to do," Munger told CNBC in 2019.

"You'll do better if you have passion for something in which you have aptitude. If Warren had gone into ballet, no one would have heard of him."

"The 'know-nothing' investor should practice diversification, but it is crazy if you are an expert. The goal of investment is to find situations where it is safe not to diversify. If you only put 20% into the opportunity of a lifetime, you are not being rational. Very seldom do we get to buy as much of any good idea as we would like to."

"Self-pity gets fairly close to paranoia, and paranoia is one of the very hardest things to reverse. You do not want to drift into self-pity. ... Self-pity will not improve the situation."

If you've got two suitors who are eager to have you, but one is way better than the other, you're going to choose that one rather than the other. That's the way we filter stock buying opportunities. Our ideas are so simple. People keep asking us for mysteries, but all we have are the most elementary ideas."

"The liabilities are always 100% good. It's the assets you have to worry about."

"It's so simple to spend less than you earn, and invest shrewdly, and avoid toxic people and toxic activities, and try and keep learning all your life, and do a lot of deferred gratification. If you do all those things, you are almost certain to succeed. If you don't, you're going to need a lot of luck."

"Well, at Berkshire, we have a simple problem of estate planning. Just hold the goddamn stock."

"Most people probably shouldn't do anything other than have index funds. … That is a perfectly rational thing to do for somebody who just doesn't want to think much about it and has no reason to think he has any advantage as a stock picker. Why should he try and pick his own stocks? He doesn't design his own electric motors and his egg beater."

"I think fewer and fewer people are really needed in stock picking. Mostly it's charlatanism to charge 3 percentage points per year or something like that to manage somebody else's money."

"I think that the modern investor, to get ahead, almost has to get in a few stocks that are way above average…. They try and have a few Apples or Googles or so on, just to keep up, because they know that a significant percentage of all the gains that come to all the common stockholders combined is going to come from a few of these super competitors."

"You have to get better and better or you will lose. Try harder, work harder and you'll do better."