O.J. Simpson, the football star and Hollywood actor acquitted of charges he killed his former wife and her friend in a trial that mesmerized the public and exposed divisions on race and policing in America, has died. He was 76.

The family announced on Simpson’s official X account that he died Wednesday of prostate cancer. He died in Las Vegas, officials there said Thursday.

Simpson earned fame, fortune, and adulation through football and show business, but his legacy was forever changed by the June 1994 knife slayings of his ex-wife, Nicole Brown Simpson, and her friend Ronald Goldman in Los Angeles. He was later found liable for the deaths in a separate civil case, and then served nine years in prison on unrelated charges.

Goldman’s father, Fred, and his sister, Kim, released a statement acknowledging that “the hope for true accountability has ended.”

“The news of Ron’s killer passing away is a mixed bag of complicated emotions and reminds us that the journey through grief is not linear,” they wrote.

Live TV coverage of Simpson’s arrest after a famous slow-speed chase marked a stunning fall from grace.

He had seemed to transcend racial barriers as the star tailback for college football’s powerful University of Southern California Trojans in the late 1960s, as a rental-car ad pitchman rushing through airports in the late 1970s, and as the husband of a blond and blue-eyed high school homecoming queen in the 1980s.

“I’m not Black, I’m O.J.,” he liked to tell friends.

His trial captured America’s attention on live TV. The case sparked debates on race, gender, domestic abuse, celebrity justice, and police misconduct.

FILE - In this Oct. 3, 1995, file photo, O.J. Simpson reacts as he is found not guilty in the death of his ex-wife Nicole Brown Simpson and her friend Ron Goldman in Los Angeles. Defense attorneys F. Lee Bailey, left, and Johnnie L. Cochran Jr. stand with him. (Myung J. Chun/Los Angeles Daily News via AP, Pool, File)

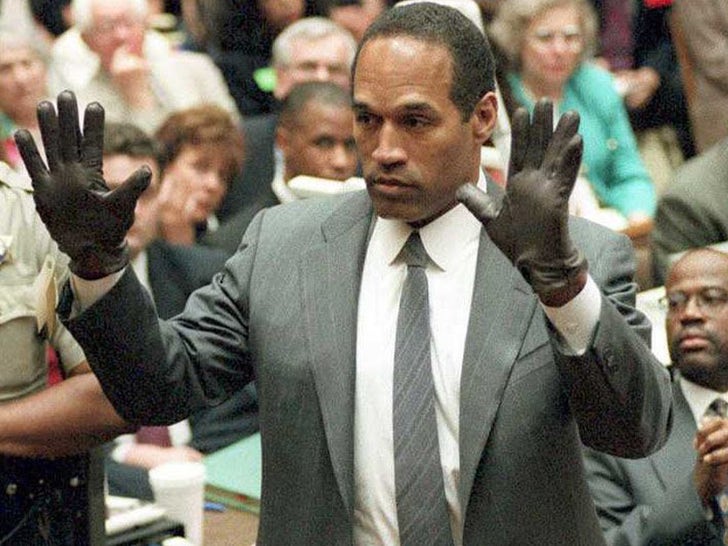

Evidence found at the scene seemed overwhelmingly against Simpson. Blood drops, bloody footprints, and a glove were there. Another glove, smeared with blood, was found at his home.

Simpson didn’t testify, but the prosecution asked him to try on the gloves in court. He struggled to squeeze them onto his hands and spoke his only three words of the trial: “They’re too small.”

His attorney Johnnie L. Cochran Jr. told the jurors, “If it doesn’t fit, you must acquit.”

The jury found him not guilty of murder in 1995, but a separate civil trial jury found him liable in 1997 for the deaths and ordered him to pay $33.5 million to relatives of Brown and Goldman.

A decade later, still shadowed by the California wrongful death judgment, Simpson led five men he barely knew into a confrontation with two sports memorabilia dealers in a cramped Las Vegas hotel room. Two men with Simpson had guns. A jury convicted Simpson of armed robbery and other felonies.

Imprisoned at 61, he served nine years in a remote Nevada lockup, including a stint as a gym janitor. He wasn’t contrite when he was released on parole in October 2017. The parole board heard him insist yet again that he was only trying to retrieve memorabilia and heirlooms stolen from him after his Los Angeles criminal trial.

“I’ve basically spent a conflict-free life, you know,” said Simpson, whose parole ended in late 2021.

Public fascination with Simpson never faded. Many debated whether he had been punished in Las Vegas for his acquittal in Los Angeles. In 2016, he was the subject of an FX miniseries and a five-part ESPN documentary.

“I don’t think most of America believes I did it,” Simpson told The New York Times in 1995, a week after a jury determined he did not kill Brown and Goldman. “I’ve gotten thousands of letters and telegrams from people supporting me.”

Twelve years later, following an outpouring of public outrage, Rupert Murdoch canceled a planned book by the News Corp.-owned HarperCollins in which Simpson offered his hypothetical account of the killings. It was to be titled “If I Did It.”

Goldman’s family, still doggedly pursuing the multimillion-dollar wrongful death judgment, won control of the manuscript. They retitled the book “If I Did It: Confessions of the Killer.”

“It’s all blood money, and unfortunately I had to join the jackals,” Simpson told The Associated Press at the time. He collected $880,000 in advance money for the book, paid through a third party.

“It helped me get out of debt and secure my homestead,” he said.

Less than two months after losing rights to the book, Simpson was arrested in Las Vegas.

Simpson played 11 NFL seasons, nine of them with the Buffalo Bills, where he became known as “The Juice” and ran behind an offensive line known as “The Electric Company.” He won four NFL rushing titles, rushed for 11,236 yards in his career, scored 76 touchdowns and played in five Pro Bowls. His best season was 1973, when he ran for 2,003 yards — the first running back to break the 2,000-yard rushing mark.

“I was part of the history of the game,” he said years later. “If I did nothing else in my life, I’d made my mark.”

Simpson’s football rise happened simultaneously with a television career. He signed a contract with ABC Sports the night he won the Heisman Trophy in 1968. That same year, he appeared on the NBC series “Dragnet” and “Ironside.” During his pro career, Simpson was a color commentator for a decade on ABC followed by a stint on NBC. In 1983, he joined ABC’s “Monday Night Football.”

Simpson became a charismatic pitchman. In 1975, Hertz made him the first Black man hired for a corporate national ad campaign. The commercials, featuring Simpson running through airports toward the Hertz desk and young girls chanting “Go, O.J., go!” were ubiquitous.

Simpson made his big-screen debut in 1974’s “The Klansman,” an exploitation film in which he starred alongside Lee Marvin and Richard Burton. The film flopped, but Simpson would go on to appear in several dozen films and TV series, including 1974’s “The Towering Inferno,” 1976’s “The Cassandra Crossing,” 1977’s “Roots” and 1977’s “Capricorn One.”

Most notable, perhaps, was 1988’s “The Naked Gun: From the Files of Police Squad” and two sequels. Simpson played Detective Nordberg in the slapstick films, opposite Leslie Nielsen.

Of course, Simpson went on to other fame.

One of the artifacts of his murder trial, the tailored tan suit he wore when acquitted, was donated and displayed at the Newseum in Washington. Simpson had been told the suit would be in the hotel room in Las Vegas, but it wasn’t there.

Orenthal James Simpson was born July 9, 1947, in San Francisco, where he grew up in government-subsidized housing.

After graduating from high school, he enrolled at City College of San Francisco for a year and a half before transferring to the University of Southern California for the spring 1967 semester.

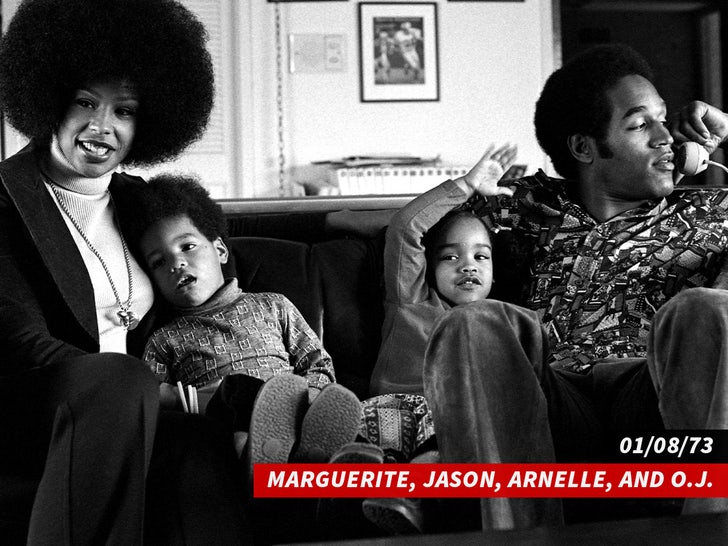

He married his first wife, Marguerite Whitley, on June 24, 1967, moving her to Los Angeles the next day so he could begin preparing for his first season with USC — which, in large part because of Simpson, won that year’s national championship.

On the day he accepted the Heisman Trophy, his first child, Arnelle, was born.

He had two sons, Jason and Aaren, with his first wife; one of those boys, Aaren, drowned as a toddler in a swimming pool accident in 1979, the same year he and Whitley divorced.

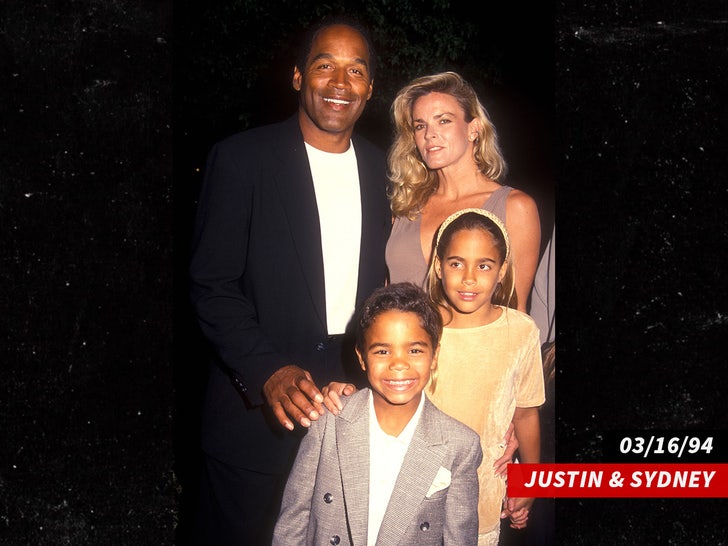

Simpson and Brown were married in 1985. They had two children, Justin and Sydney, and divorced in 1992. Two years later, Nicole Brown Simpson was found dead.

“We don’t need to go back and relive the worst day of our lives,” he told AP 25 years after the double slayings. “The subject of the moment is the subject I will never revisit again. My family and I have moved on to what we call the ‘no negative zone.’ We focus on the positives.”

A dog’s plaintive wail. A courtroom couplet-turned-cultural catchphrase about gloves. A judge and attorneys who became media darlings and villains. A slightly bewildered houseguest elevated, briefly, into a slightly bewildered celebrity. Troubling questions about race echo still. The beginning of the Kardashian dynasty. An epic slow-motion highway chase. And, lest we forget, two people whose lives ended brutally.

And a nation watched — a nation far different than today’s, where the ravenousness for reality television has multiplied. The spectator mentality of those jumbled days in 1994 and 1995, then novel, has since become an intrinsic part of the American fabric. Smack at the center of the national conversation was O.J. Simpson, one of the most curious cultural figures in recent U.S. history.

Simpson’s death Wednesday, almost exactly three decades after the killings that changed his reputation from football hero to suspect, summoned remembrances of an odd moment in time — no, let’s call it what it was, which was deeply weird — in which a smartphone-less country craned its neck toward clunky TVs to watch a Ford Bronco inch its way along a California freeway.

“It was an incredible moment in American history,” said Wolf Blitzer, anchoring coverage of Simpson’s death Thursday on CNN. What made it so — beyond, of course, tabloid culture and the fundamental news value of such a famous person accused in such brutal killings?

THE SAGA ANTICIPATED 21ST CENTURY MEDIA

In an era when the internet as we know it was still being born, when “platform” was still just a place to board a train, Simpson was a unique breed of celebrity. He was truly transmedia, a harbinger of the digital age — a walking, talking crossover story for multiple audiences.

He was sports — the very pinnacle of football excellence. He was in stardom, not only for his athletic prowess but for his Hertz-hawking run through airports on TV and his acting in movies like “The Naked Gun.” He embodied societal questions about race, class, and money long before Nicole Brown Simpson and Ronald Goldman were stabbed to death on June 12, 1994.

Then came the saga, beginning with the killings and ending — only technically — in a Los Angeles courtroom more than a year later. The most epic of American novels had nothing on this period of the mid-1990s. Americans watched. Americans talked about watching. Americans debated. Americans judged. And Americans watched some more.

The generations-old chasm between white Americans and Black Americans was not helped by Time magazine’s decision to tactically darken Simpson’s mugshot on its cover for a dramatic — and, many said, racist — effect. For those who lived through that period, it’s hard to remember much in the public sphere that wasn’t crowded out by the O.J. storyline and its many components, including the subsequent civil trial that found Simpson liable for the deaths. One newspaper even ran a series of possible endings to the storyline, written by mystery novelists.

Sure, people were saying different things. But it was, inarguably, a national conversation.

FILE- Defendant O.J. Simpson is surrounded by his defense attorneys, from left, Johnnie L. Cochran Jr., Peter Neufeld, Robert Shapiro, Robert Kardashian, and Robert Blasier, seated at left, at the close of defense arguments in his murder trial, Thursday, Sept. 28, 1995, in Los Angeles. Simpson, the decorated football superstar and Hollywood actor who was acquitted of charges he killed his former wife and her friend but later found liable in a separate civil trial, has died. He was 76. (Sam Mircovich/Pool Photo via AP, File)

The nation — and its media — are far more fragmented now. Rarely these days do Americans gather around the virtual campfire for a common experience; instead, small brush fires draw niche crowds in virtual corners for equally intense, but smaller, common experiences. This week’s eclipse was a rare exception.

In 1994, everyday real-time, wall-to-wall coverage was still emerging. Sure, we had Walter Cronkite during the Kennedy assassination and again during the chaotic 1968 Democratic National Convention. The first Gulf War in 1991 firmly cemented live TV expectations. But coverage of the Bronco chase and the trial fed the appetite in a way no other event did. Even now, such universal viewership is rare.

“The media we consume is much more diffuse now. It’s so rare that we’re all glued to the same spectacle,” said Danielle Lindemann, author of the 2022 book “True Story: What Reality TV Says About Us.”

“In 1994 we were watching our television sets and following along with news coverage,” Lindemann, a professor of sociology at Lehigh University, said in an email. “But there wasn’t that parallel discourse happening via social media.”

CONNECTIONS BETWEEN THEN AND NOW

The connections between the Simpson saga and today aren’t hard to find.

Judges and lawyers in high-profile cases are now regular fodder for the spotlight. One of Simpson’s attorneys, Robert Kardashian, paved the way for the next generation of his family to change the very face of how celebrity operates. A local Los Angeles TV reporter who covered the case, Harvey Levin, went on to establish TMZ, a luridly foundational pillar of modern multiplatform celebrity coverage — and the outlet that broke the news of Simpson’s death.

FILE - Members of the crowd react to O.J. Simpson leaving Los Angeles County Superior Court, Tuesday, Feb. 4, 1997, in Santa Monica, Calif. after hearing the verdict in the wrongful-death civil trial against O.J. Simpson. Simpson, the decorated football superstar and Hollywood actor who was acquitted of charges he killed his former wife and her friend but later found liable in a separate civil trial, has died. He was 76. (AP Photo/Susan Sterner, File)

And of course, as with so many American stories, there is the question of race.

Simpson’s acquittal on murder charges revealed a fundamental fault line: Some Black people welcomed the verdict, while many white people were in disbelief. Simpson probably confused matters more over the years by saying, famously, “I’m not Black. I’m O.J.” But for many Black Americans who felt their interactions with police and the courts had produced unjust results, the acquittal was a notable exception.

“There was a sense that it’s only justice for a rich Black man to get off when a rich white man would,” said John Baick, a professor of history at Western New England University.

Three decades on, that conversation isn’t over — he’s certainly still discussing it with students. On Thursday, Baick invoked Simpson to talk about race, fame, and wealth in class; only after it ended did he find out his subject had died.

A generation has passed since these events were fresh. And after thousands of hours of video, millions of written words, and countless talking heads weighing in, the O.J. Simpson case stands as two things: an American moment like no other, and an interlude that contained so much of what American culture is and was becoming.

From the old, weird America, it got the obsession with violent true crime and its quirky cast of film noir villains and heroes, not to mention the tragedy and the whodunit. And it was a teaser trailer of the emerging, fragmenting internet culture that would, in a few years, give us smartphones, social media, reality-TV saturation, and live coverage of just about everything.

Was it, as so many said so loudly, “the trial of the century”? That’s subjective. But any culture is made up of small bits, and the Simpson case left many of those in its wake. This much is incontrovertibly true: After the slow-speed chase, American media culture got a whole lot faster really quickly. So fast, in fact, that many of the central questions around the case — about race, justice, and how we consume murder and misery as just another set of consumer products — linger unanswered.

“Where does this fit in? What do Americans think about this now?” Baick wonders. ”What you think about O.J. Simpson might be a litmus test for a long time still.”

O.J. Simpson was surrounded by family in the final days before his death, and that includes all of his living children -- yes, even the 2 youngest he had with Nicole Brown Simpson.

Sources with direct knowledge tell TMZ ... everyone who came to visit O.J. at his home in the days before he passed had to sign NDAs for his privacy -- that went for friends, family, and even medical personnel who were coming into contact with him while he was under hospice care.

We're told on Friday, a medical professional checked on O.J. and notified those around him that he was starting to transition -- and that's when everyone came flocking to his bedside.

It's unclear exactly when his 4 children arrived, but by the end ... they were all there as he died peacefully. The family members included his 2 children with Nicole -- Sydney and Justin -- and his 2 older ones with Marguerite Whitley ... Jason and Arnelle.

It might shock some to hear that Justin and Sydney were in the mix ... as their mother was brutally murdered, allegedly by their father.

While Simpson was acquitted of the murder charges, he was later found civilly liable for Nicole's death and Ron Goldman's. In the aftermath of all that, O.J. raised Justin and Sydney.

They've never spoken publicly about the whole saga, so we don't know how they feel about it. Nor is it clear how close of a relationship they maintained with O.J. in their adulthood. Sydney is now 38, and Justin is 35.

Aside from family members ... we're told dozens of friends went to visit Simpson in his final days. As we reported, his remaining close friends flew in to say their goodbyes.

Our sources say somewhere between 30 to 50 people -- consisting of friends and other family -- saw O.J. in person. They all signed the NDAs, and no phones were allowed in the room with him.

Like we told you, he was in very poor health before dying ... and couldn't talk much. Still, these folks got some face time with him and said their farewells.

The June 12, 1994, killings of Nicole Brown Simpson and her friend Ronald Goldman brought what’s dubbed the “Trial of the Century” that culminated with O.J. Simpson’s acquittal of the murders. The announcement Thursday that Simpson is dead has brought renewed attention to the closely watched trial and the fascinating cast of characters who played a role in the case.

Here’s a look at where they are now.

O.J. Simpson was surrounded by family in the final days before his death, and that includes all of his living children -- yes, even the 2 youngest he had with Nicole Brown Simpson.

Sources with direct knowledge tell TMZ ... everyone who came to visit O.J. at his home in the days before he passed had to sign NDAs for his privacy -- that went for friends, family, and even medical personnel who were coming into contact with him while he was under hospice care.

We're told on Friday, a medical professional checked on O.J. and notified those around him that he was starting to transition -- and that's when everyone came flocking to his bedside.

It's unclear exactly when his 4 children arrived, but by the end ... they were all there as he died peacefully. The family members included his 2 children with Nicole -- Sydney and Justin -- and his 2 older ones with Marguerite Whitley ... Jason and Arnelle.

It might shock some to hear that Justin and Sydney were in the mix ... as their mother was brutally murdered, allegedly by their father.

While Simpson was acquitted of the murder charges, he was later found civilly liable for Nicole's death and Ron Goldman's. In the aftermath of all that, O.J. raised Justin and Sydney.

They've never spoken publicly about the whole saga, so we don't know how they feel about it. Nor is it clear how close of a relationship they maintained with O.J. in their adulthood. Sydney is now 38, and Justin is 35.

Aside from family members ... we're told dozens of friends went to visit Simpson in his final days. As we reported, his remaining close friends flew in to say their goodbyes.

Our sources say somewhere between 30 to 50 people -- consisting of friends and other family -- saw O.J. in person. They all signed the NDAs, and no phones were allowed in the room with him.

Like we told you, he was in very poor health before dying ... and couldn't talk much. Still, these folks got some face time with him and said their farewells.

The June 12, 1994, killings of Nicole Brown Simpson and her friend Ronald Goldman brought what’s dubbed the “Trial of the Century” that culminated with O.J. Simpson’s acquittal of the murders. The announcement Thursday that Simpson is dead has brought renewed attention to the closely watched trial and the fascinating cast of characters who played a role in the case.

Here’s a look at where they are now.

THE DEFENDANT

Two years after Simpson’s 1995 acquittal, a civil court jury found him liable for the deaths of his ex-wife and Goldman and ordered he pay their survivors $33.5 million. He got into a series of minor legal scrapes ranging from a 2001 Florida road-rage incident to racing his boat through a protected Florida manatee zone in 2002; He was acquitted for the former and fined for the latter.

His most serious transgression came in 2007, however, when he and five others barged into a Las Vegas hotel room with guns and seized property from memorabilia dealers that Simpson claimed to own. He served nine years in a Nevada prison and was paroled in 2017. In recent years, Simpson lived quietly in Las Vegas, where he played golf and sometimes posed for selfies with those still enamored with his celebrity.

He died Wednesday from prostate cancer.

Two years after Simpson’s 1995 acquittal, a civil court jury found him liable for the deaths of his ex-wife and Goldman and ordered he pay their survivors $33.5 million. He got into a series of minor legal scrapes ranging from a 2001 Florida road-rage incident to racing his boat through a protected Florida manatee zone in 2002; He was acquitted for the former and fined for the latter.

His most serious transgression came in 2007, however, when he and five others barged into a Las Vegas hotel room with guns and seized property from memorabilia dealers that Simpson claimed to own. He served nine years in a Nevada prison and was paroled in 2017. In recent years, Simpson lived quietly in Las Vegas, where he played golf and sometimes posed for selfies with those still enamored with his celebrity.

He died Wednesday from prostate cancer.

THE VICTIMS’ FAMILIES

Ron Goldman’s sister, Kim, was 22 and broke into sobs when the not-guilty verdict was read. Since then, she counseled troubled teens as executive director of a Southern California-based nonprofit, The Youth Project, until it closed during the pandemic. A best-selling author and public speaker, Goldman also has launched several podcasts including “Confronting: OJ Simpson” and, most recently, ”Media Circus.”

Fred Goldman, Ron’s father, has relentlessly pursued Simpson through civil courts, maintaining it is the only way to achieve justice for his son. Goldman’s family has seized some of Simpson’s memorabilia, including his 1968 Heisman Trophy as college football’s best player that year. The family has also taken the rights to Simpson’s movies, a book he wrote about the killings, and other items to satisfy part of the $33.5 million judgment that Simpson refused to pay.

Denise Brown, Nicole Brown Simpson’s sister, has remained the family’s most outspoken critic of Simpson, although, like the Goldman family, she refuses to speak his name. The former model has become a victims’ rights advocate and a speaker, urging both women and men to leave abusive relationships. She said she has moved past her anger with God for the killings but has never forgiven Simpson, and will not watch any films or documentaries about the killings.

Ron Goldman’s sister, Kim, was 22 and broke into sobs when the not-guilty verdict was read. Since then, she counseled troubled teens as executive director of a Southern California-based nonprofit, The Youth Project, until it closed during the pandemic. A best-selling author and public speaker, Goldman also has launched several podcasts including “Confronting: OJ Simpson” and, most recently, ”Media Circus.”

Fred Goldman, Ron’s father, has relentlessly pursued Simpson through civil courts, maintaining it is the only way to achieve justice for his son. Goldman’s family has seized some of Simpson’s memorabilia, including his 1968 Heisman Trophy as college football’s best player that year. The family has also taken the rights to Simpson’s movies, a book he wrote about the killings, and other items to satisfy part of the $33.5 million judgment that Simpson refused to pay.

Denise Brown, Nicole Brown Simpson’s sister, has remained the family’s most outspoken critic of Simpson, although, like the Goldman family, she refuses to speak his name. The former model has become a victims’ rights advocate and a speaker, urging both women and men to leave abusive relationships. She said she has moved past her anger with God for the killings but has never forgiven Simpson, and will not watch any films or documentaries about the killings.

THE LEGAL DREAM TEAM

Johnnie L. Cochran, Jr., Simpson’s lead attorney, died of brain cancer in 2005 at 68. His refrain to jurors — “If it doesn’t fit, you must acquit” — sought to underscore that the bloody gloves found at Simpson’s home and the crime scene were too small for the football legend when he tried them on in court. After the trial, that line became a national catchphrase. Following the trial, Cochran expanded his law firm to 15 states and frequently appeared on television. He also became the inspiration for Jackie Chiles, the bombastic lawyer character on the TV sitcom “Seinfeld.”

Another key part of the defense team, Robert Kardashian, died of esophageal cancer in 2003 at age 59. A longtime friend of Simpson’s, he renewed his law license specifically to represent him in the trial. Between the time of the murders and his arrest, Simpson stayed in Kardashian’s home. When Simpson fled authorities in a white Ford Bronco on June 17, 1994, Kardashian read to reporters a rambling message Simpson had left behind as a historic freeway chase unfolded on national television. Since his death, Kardashian’s fame has been eclipsed by that of ex-wife Kris, and children Kourtney, Kim, Khloe, and Rob, thanks to their reality TV show, “Keeping Up With the Kardashians.”

Robert Shapiro, the first member of Simpson’s defense team, continues to practice law. In 2005, he created a foundation that grants college scholarships to 11- to 18-year-olds for staying sober after his 24-year-old son died of an overdose.

Barry Scheck was the lawyer who introduced DNA science to jurors and undermined the prosecution’s forensic evidence by attacking the collection methods. He and fellow defense lawyer Peter Neufeld co-founded The Innocence Project in 1992. It uses DNA evidence to exonerate people who were wrongly convicted.

F. Lee Bailey was the lawyer who played a key role in exposing racist statements made by one of the prosecution’s key witnesses, police Detective Mark Fuhrman, which undermined his credibility. When he joined the defense team, Bailey already was famous for his role in some of the most high-profile cases of the 20th century, including that of heiress-turned-bank-robber Patricia Hearst. Bailey was disbarred in Massachusetts and Florida in the early 2000s for misconduct in handling a client’s case. He died in 2021.

Alan Dershowitz, a Harvard law professor emeritus, also helped Simpson get an acquittal and consulted on the scientific aspects of the case. Since then, he courted controversy by helping the late hedge fund manager and sex offender Jeffrey Epstein win a lenient sentence for abusing underaged girls. He was also part of President Donald Trump’s impeachment defense team that ended with his acquittal.

Johnnie L. Cochran, Jr., Simpson’s lead attorney, died of brain cancer in 2005 at 68. His refrain to jurors — “If it doesn’t fit, you must acquit” — sought to underscore that the bloody gloves found at Simpson’s home and the crime scene were too small for the football legend when he tried them on in court. After the trial, that line became a national catchphrase. Following the trial, Cochran expanded his law firm to 15 states and frequently appeared on television. He also became the inspiration for Jackie Chiles, the bombastic lawyer character on the TV sitcom “Seinfeld.”

Another key part of the defense team, Robert Kardashian, died of esophageal cancer in 2003 at age 59. A longtime friend of Simpson’s, he renewed his law license specifically to represent him in the trial. Between the time of the murders and his arrest, Simpson stayed in Kardashian’s home. When Simpson fled authorities in a white Ford Bronco on June 17, 1994, Kardashian read to reporters a rambling message Simpson had left behind as a historic freeway chase unfolded on national television. Since his death, Kardashian’s fame has been eclipsed by that of ex-wife Kris, and children Kourtney, Kim, Khloe, and Rob, thanks to their reality TV show, “Keeping Up With the Kardashians.”

Robert Shapiro, the first member of Simpson’s defense team, continues to practice law. In 2005, he created a foundation that grants college scholarships to 11- to 18-year-olds for staying sober after his 24-year-old son died of an overdose.

Barry Scheck was the lawyer who introduced DNA science to jurors and undermined the prosecution’s forensic evidence by attacking the collection methods. He and fellow defense lawyer Peter Neufeld co-founded The Innocence Project in 1992. It uses DNA evidence to exonerate people who were wrongly convicted.

F. Lee Bailey was the lawyer who played a key role in exposing racist statements made by one of the prosecution’s key witnesses, police Detective Mark Fuhrman, which undermined his credibility. When he joined the defense team, Bailey already was famous for his role in some of the most high-profile cases of the 20th century, including that of heiress-turned-bank-robber Patricia Hearst. Bailey was disbarred in Massachusetts and Florida in the early 2000s for misconduct in handling a client’s case. He died in 2021.

Alan Dershowitz, a Harvard law professor emeritus, also helped Simpson get an acquittal and consulted on the scientific aspects of the case. Since then, he courted controversy by helping the late hedge fund manager and sex offender Jeffrey Epstein win a lenient sentence for abusing underaged girls. He was also part of President Donald Trump’s impeachment defense team that ended with his acquittal.

THE PROSECUTORS

Marcia Clark, the trial’s lead prosecutor, quit law after the trial, although she has appeared frequently over the years as a TV commentator on high-profile trials. She was paid $4 million for her 2016 memoir, “Without a Doubt,” and has gone on to write a series of crime novels.

Chris Darden, the co-prosecutor, was criticized for having Simpson try on the bloody gloves in the courtroom without first ensuring they would fit. He is now a defense attorney himself. He represented the man charged with killing hip-hop mogul Nipsey Hussle before withdrawing from the case, saying his family had received death threats. Darden has also taught law, appeared on television as a legal commentator, and wrote about the Simpson trial in the 1996 book, “In Contempt.” Currently, he is running for Los Angeles County Superior Court judge.

Marcia Clark, the trial’s lead prosecutor, quit law after the trial, although she has appeared frequently over the years as a TV commentator on high-profile trials. She was paid $4 million for her 2016 memoir, “Without a Doubt,” and has gone on to write a series of crime novels.

Chris Darden, the co-prosecutor, was criticized for having Simpson try on the bloody gloves in the courtroom without first ensuring they would fit. He is now a defense attorney himself. He represented the man charged with killing hip-hop mogul Nipsey Hussle before withdrawing from the case, saying his family had received death threats. Darden has also taught law, appeared on television as a legal commentator, and wrote about the Simpson trial in the 1996 book, “In Contempt.” Currently, he is running for Los Angeles County Superior Court judge.

THE JUDGE

Lance Ito retired in 2015 after presiding over approximately 500 trials. Simpson’s trial made him such a household name that “The Tonight Show” briefly featured a comedy segment called “The Dancing Itos,” in which lookalikes performed in judicial robes. After the Simpson trial, he had to remove his name plate from his courtroom door because people kept stealing it. It has never discussed the trial publicly, citing judicial ethics.

Lance Ito retired in 2015 after presiding over approximately 500 trials. Simpson’s trial made him such a household name that “The Tonight Show” briefly featured a comedy segment called “The Dancing Itos,” in which lookalikes performed in judicial robes. After the Simpson trial, he had to remove his name plate from his courtroom door because people kept stealing it. It has never discussed the trial publicly, citing judicial ethics.

THE HOUSEGUEST

Brian “Kato” Kaelin, a struggling actor living in a guest house on Simpson’s property, testified he heard a “bump” during the night of the murders and went outside to find Simpson in the yard. Prosecutors later said Kaelin’s testimony showed Simpson was sneaking back home after the killings. Mocked on talk shows as America’s most famous houseguest, Kaelin has gone on to appear on reality shows, as well as in small parts in TV sitcoms and films, and to launch a loungewear clothing line.

O.J. Simpson died Thursday without having paid the lion’s share of the $33.5 million judgment a California civil jury awarded to the families of his ex-wife Nicole Brown Simpson and her friend Ron Goldman.

Acquitted at a criminal trial, Simpson was found liable by jurors in a 1997 wrongful death lawsuit.

The public is now likely to get a closer look at Simpson’s finances, and the families are likely to have a better shot at collecting — if there is anything to collect.

Here’s how the next few months may play out.

Brian “Kato” Kaelin, a struggling actor living in a guest house on Simpson’s property, testified he heard a “bump” during the night of the murders and went outside to find Simpson in the yard. Prosecutors later said Kaelin’s testimony showed Simpson was sneaking back home after the killings. Mocked on talk shows as America’s most famous houseguest, Kaelin has gone on to appear on reality shows, as well as in small parts in TV sitcoms and films, and to launch a loungewear clothing line.

O.J. Simpson died Thursday without having paid the lion’s share of the $33.5 million judgment a California civil jury awarded to the families of his ex-wife Nicole Brown Simpson and her friend Ron Goldman.

Acquitted at a criminal trial, Simpson was found liable by jurors in a 1997 wrongful death lawsuit.

The public is now likely to get a closer look at Simpson’s finances, and the families are likely to have a better shot at collecting — if there is anything to collect.

Here’s how the next few months may play out.

THE PROBATE PROCESS

Whether or not he left behind a will, and whatever that document says, Simpson’s assets will now almost certainly have to go through what’s known as the probate process in court before his four children or other intended heirs can collect on any of them.

Different states have different probate laws. Generally, the case is filed in the state where the person was living when they died. In Simpson’s case, that’s Nevada. But if significant assets are in California or Florida, where he also lived at various times, separate cases could emerge there.

Nevada law says an estate must go through the courts if its assets exceed $20,000, or if any real estate is involved, and this must be done within 30 days of the death. If a family fails to file documents, creditors themselves can begin the process.

Whether or not he left behind a will, and whatever that document says, Simpson’s assets will now almost certainly have to go through what’s known as the probate process in court before his four children or other intended heirs can collect on any of them.

Different states have different probate laws. Generally, the case is filed in the state where the person was living when they died. In Simpson’s case, that’s Nevada. But if significant assets are in California or Florida, where he also lived at various times, separate cases could emerge there.

Nevada law says an estate must go through the courts if its assets exceed $20,000, or if any real estate is involved, and this must be done within 30 days of the death. If a family fails to file documents, creditors themselves can begin the process.

A STRONGER CLAIM IN DEATH?

Once the case is in court, creditors who say they are owed money can then seek a piece of the assets. The Goldman and Brown families will be on at least equal footing with other creditors, and will probably have an even stronger claim.

Under California law, creditors holding a judgment lien like the plaintiffs in the wrongful death case are deemed to have secured debt, and have priority over creditors with unsecured debt. And they are in a better position to get paid than they were before the defendant’s death.

Arash Sadat, a Los Angeles attorney who specializes in property disputes, says it is “100%” better for the claimant to have the debtor be deceased and their money in probate.

He said his firm had a jury trial where their clients got a $9 million jury award that the debtor appealed and delayed endlessly.

”He did everything he could to avoid paying this debt,” Sadat said. “Three or four years later, he died. And within weeks, the estate cuts a check for $12 million. That’s the $9 million plus interest that I had accrued over this time.”

The executor or administrator of the estate has much more of an incentive to dispense with debts than the living person does. “That’s why you see things like that happening,” Sadat said.

But of course that doesn’t mean payment will be forthcoming.

“I do think it’s going to be quite difficult for them to collect,” attorney Christopher Melcher said. “We don’t know what O.J. has been able to earn over the years.”

Neither Sadat nor Melcher is involved with the Simpson estate or the court case.

Once the case is in court, creditors who say they are owed money can then seek a piece of the assets. The Goldman and Brown families will be on at least equal footing with other creditors, and will probably have an even stronger claim.

Under California law, creditors holding a judgment lien like the plaintiffs in the wrongful death case are deemed to have secured debt, and have priority over creditors with unsecured debt. And they are in a better position to get paid than they were before the defendant’s death.

Arash Sadat, a Los Angeles attorney who specializes in property disputes, says it is “100%” better for the claimant to have the debtor be deceased and their money in probate.

He said his firm had a jury trial where their clients got a $9 million jury award that the debtor appealed and delayed endlessly.

”He did everything he could to avoid paying this debt,” Sadat said. “Three or four years later, he died. And within weeks, the estate cuts a check for $12 million. That’s the $9 million plus interest that I had accrued over this time.”

The executor or administrator of the estate has much more of an incentive to dispense with debts than the living person does. “That’s why you see things like that happening,” Sadat said.

But of course that doesn’t mean payment will be forthcoming.

“I do think it’s going to be quite difficult for them to collect,” attorney Christopher Melcher said. “We don’t know what O.J. has been able to earn over the years.”

Neither Sadat nor Melcher is involved with the Simpson estate or the court case.

WHAT ASSETS DID SIMPSON HAVE?

Simpson said he lived only on his NFL and private pensions. Hundreds of valuable possessions were seized as part of the jury award, and Simpson was forced to auction his Heisman Trophy, fetching $230,000.

Goldman’s father Fred Goldman, the lead plaintiff, always said the issue was never the money, it was only about holding Simpson responsible. And he said in a statement Thursday that with Simpson’s death, “the hope for true accountability has ended.”

Simpson said he lived only on his NFL and private pensions. Hundreds of valuable possessions were seized as part of the jury award, and Simpson was forced to auction his Heisman Trophy, fetching $230,000.

Goldman’s father Fred Goldman, the lead plaintiff, always said the issue was never the money, it was only about holding Simpson responsible. And he said in a statement Thursday that with Simpson’s death, “the hope for true accountability has ended.”

WHAT ABOUT TRUSTS?

There are ways that a person can use trusts established during their life and other methods to make sure their chosen heirs get their assets in death. If such a trust is irrevocable, it can be especially strong.

But transfers of assets to others that are made to avoid creditors can be deemed fraudulent, and claimants like the Goldman and Brown families can file separate civil lawsuits that bring those assets into dispute.

There are ways that a person can use trusts established during their life and other methods to make sure their chosen heirs get their assets in death. If such a trust is irrevocable, it can be especially strong.

But transfers of assets to others that are made to avoid creditors can be deemed fraudulent, and claimants like the Goldman and Brown families can file separate civil lawsuits that bring those assets into dispute.

.webp)