Simone Biles fell off the balance beam on her last day of competition in the 2024 Olympics, earning a score of 13.100 which left her in fifth place. Italy’s Alice D’Amato took the gold.

Biles’ fellow Team USA gymnast, Sunisa Lee, also fell in her beam routine.

Was all that toil since the last Olympics — all the work on the practice track and in the weight room in the name of finding a centimeter here or a millisecond there — really going to be worth all the trouble?

Ten seconds passed, then 20. Then, nearly 30. And then, the answer popped up.

Yes, Lyles is the 100-meter champion at the Paris Olympics. The World’s Fastest Man.

Just not by very much.

The American showman edged out Jamaica’s Kishane Thompson on Sunday by five-thousandths of a second — that’s .005 of one tick of the clock — in a race for the ages.

The final tally in this one: Lyles 9.784 seconds, Thompson 9.789.

The new champion said that before he left for Paris, one of his physio guys ensured him this race would be a squeaker.

“He said, ‘This is how close first and second are going to be,’” Lyles said as he pinched his thumb and his forefinger together so they were almost touching. “I can’t believe how right he was.”

For perspective, the blink of an eye takes, on average, .1 second. That was 20 times longer than the gap between first and second.

It was so close, that when the sprinters crossed the line and the word “Photo” popped up next to the names of Lyles, Thompson, and five others in the eight-man field, Lyles walked over to the Jamaican and said, “I think you got the Olympics dog.”

Thompson, who raced three lanes to the left of Lyles and had no clue where he was on the track, wasn’t convinced.

“I was, ‘Wow, I’m not even sure, because it was that close,’” the Jamaican said.

Time will tell. It always does. When Lyles’ name came up first, he snatched his name tag off the front of his bib and held it to the sky. Moments later, he shouted at the TV camera: “America, I told you I got this!”

The first four racers were separated by less than .03. The top seven all finished within .09 of each other.

America’s Fred Kerley came in third at 9.81. “That’s probably one of the most beautiful races I’ve been in,” he said.

In the photo finish, Kerley’s orange shoe crossed the line before anyone or anything. But it’s the chest breaking the barrier that counts. Lyles’ chest crossed first.

This was the closest 1-2 finish in the 100 since at least Moscow in 1980 — or maybe even ever.

Back then, Britain’s Allan Wells narrowly beat Silvio Leonard in an era when the electronic timers didn’t go into the thousandths of a second. The same was true in 1932 when Eddie Tolan won the Olympics’ first-ever photo finish.

Lyles conceded that during the excruciating wait, he was pretty sure he had dipped his chest just a tad too soon. Dipping, it turns out, is one of the few things he doesn’t work on over and over again at his training track in Florida.

“But I would say I have a decent history with dipping,” he said, recalling races he won in high school and as a junior.

The 9.784 marked a new personal best for Lyles and made him the first American champion in the marquee race at the Olympics since Justin Gatlin in 2004.

Lyles is hoping to go even bigger than that, and maybe take this sport back to a day when it was Carl Lewis and Edwin Moses lighting up the track — a must-see affair, the likes of which Lyles headlined in front of around 80,000 on a warm night at the Stade de France.

The mission started after Lyles settled for a bronze medal in Tokyo in his favorite — and then, only — sprint, the 200. Those COVID-impacted Games were a terrible experience for Lyles. He rededicated himself to bettering his mental health but also looked for a new mission — the 100 meters and, with it, a chance at track immortality.

The practice was tough for a sprinter never known as a great starter, but he stuck with it. When he won the world championships last year, then backed it up by winning the 200, his goal for Paris was very much in sight.

But when he came into the Olympic final having finished second in both his qualifying races and staring across at one sprinter who had run faster than him this year — Thompson — and another who had beaten him twice this year — Jamaica’s Oblique Seville — he knew this would be no coronation.

Thompson added another roadblock when, during the introduction, he let out a primal scream, the likes of which Lyles has been unleashing in some of his biggest races.

“I thought ‘Man, that’s my thing, that’s crazy,’” Lyles said.

Lyles galloped and leaped about 20 yards down the track before returning to the starting line, where the runners waited some three minutes for the gun to finally sound.

It was worth the wait.

Now, the question that could be debated for years is: What was the difference in this one?

Could it have been Lyles’ closing speed and that lean into the line that he thought was mistimed?

Was it his ability to stay in reach of every one among this straight line of sprinters over the first 60 meters — a skill he’s been working on in tedious practice after practice since he took on the shorter sprint?

The answer: all that and more.

“Everyone in the field came out knowing they could win this race,” Lyles said.

It took 9.784 seconds, then about 30 seconds more, for the scoreboard to flash the name of the man who actually did.

“Seeing that name, I was like ‘Oh my gosh, there it is!’” Lyles said.

Gold (and bronze) for Ukrainian high jumpers

Yaroslava Mahuchikh won Olympic gold in the high jump for her war-torn country of Ukraine and, as a bonus, had company. Her teammate Iryna Gerashchenko won the bronze and the teammates hopped, skipped, and jumped around the track parading their blue-and-yellow flags in a heartfelt celebration.

Mahuchikh needed fewer tries to clear the winning height of 2 meters than Australia’s Nicola Olyslagers, and so, added the sport’s biggest prize of all — Olympic gold — to her world championship and world record.

Kerr vs Ingebrigtsen is a go for heated men’s 1,500

The best rivalry in track will culminate Tuesday when reigning world champion Josh Kerr of Britain takes on defending Olympic champion Jakob Ingebrigtsen of Norway.

They squared off in Sunday’s semifinal, too, and Ingebrigtsen edged out the Brit, looking over to him twice as they surged down the homestretch, to win a race that felt like it meant more than it should have in 3:32.38.

“They should be expecting one of the most vicious and hardest 1,500s the sport’s seen in a very long time,” Kerr said.

Did Ingebrigtsen agree?

“Depends who you ask, maybe,” he said. “I mean, racing is what you want it to be.”

Olympic boxer Imane Khelif said the wave of hateful scrutiny she has faced over misconceptions about her gender “harms human dignity,” and she called for an end to bullying athletes after being greatly affected by the international backlash against her.

The Algerian athlete spoke about her tumultuous Olympic experience on Sunday night in an interview with SNTV, a sports video partner of The Associated Press.

“I send a message to all the people of the world to uphold the Olympic principles and the Olympic Charter, to refrain from bullying all athletes, because this has effects, massive effects,” Khelif said in Arabic. “It can destroy people, it can kill people’s thoughts, spirit, and mind. It can divide people. And because of that, I ask them to refrain from bullying.”

The victories of Khelif and fellow boxer Lin Yu-ting of Taiwan in the ring in Paris have become one of the biggest stories of the Paris Games. Both women have clinched their first Olympic medals even as they have faced online abuse based on unsubstantiated claims about their gender, drawing them into a wider divide over changing attitudes toward gender identity and regulations in sports.

The 25-year-old Khelif acknowledged the pressure and pain of enduring this ordeal while competing far from home in the most important event of her athletic career.

“I am in contact with my family two days a week. I hope that they weren’t affected deeply,” she said. “They are worried about me. God willing, this crisis will culminate in a gold medal, and that would be the best response.”

The vitriol stems from claims by the International Boxing Association, which has been permanently banned from the Olympics, that both Khelif and Lin failed unspecified eligibility tests for the women’s competition at last year’s world championships.

Khelif declined to answer when asked whether she had undergone tests other than doping tests, saying she didn’t want to talk about it.

She expressed gratitude to the International Olympic Committee and its president, Thomas Bach, for standing resolutely behind her while the banned former governing body of Olympic boxing stoked a furor around her participation in Paris.

“I know that the Olympic Committee has done me justice, and I am happy with this remedy because it shows the truth,” she said.

She also has seen massive support at her bouts, drawing cheers when she enters the arena and crowds waving Algerian flags chanting her first name. She will fight again Tuesday in the women’s 66-kilogram semifinals at Roland Garros.

Khelif repeatedly made clear she won’t allow chatter or accusations to deter her from attempting to claim Algeria’s first Olympic gold medal in women’s boxing.

“I don’t care about anyone’s opinion,” Khelif said a day after beating Anna Luca Hamori of Hungary. “I came here for a medal, and to compete for a medal. I will certainly be competing to improve (and) be better, and God willing, I will improve, like every other athlete.”

Although she is aware of the worldwide discussion about her, Khelif said she has been somewhat removed.

“Honestly, I don’t follow social media,” she said. “There is a mental health team that doesn’t let us follow social media, especially in the Olympic Games, whether me or other athletes. I’m here to compete and get a good result.”

Khelif started her Olympic run last Thursday with a victory over Angela Carini of Italy, who abandoned the bout after just 46 seconds. Carini later said she regretted her decision and wished to apologize to Khelif.

That unusual ending raised the chatter around Khelif into a roar, drawing comments from the likes of former U.S. President Donald Trump, “Harry Potter” writer J.K. Rowling, and others falsely claiming Khelif was a man or transgender.

The IOC repeatedly declared she and Lin qualified to participate in the Olympics, and it has decried the murky testing standards and untransparent governance of the IBA, which was banished entirely from the Olympics last year in an unprecedented punishment for a governing body.

Khelif clearly felt the weight of the worldwide scrutiny upon her, and her victory over Hamori on Saturday appeared to be cathartic. After the referee raised Khelif’s hand with the win, she went to the center of the ring, waved to her fans, knelt, and slammed her palm on the canvas, her smile turning to tears.

“I couldn’t control my nerves,” Khelif said in the interview. “Because after the media frenzy and after the victory, there was a mix of joy and at the same time, I was greatly affected, because honestly, it wasn’t an easy thing to go through at all. It was something that harms human dignity.”

She had competed in IBA events for several years without problems until she was abruptly suspended from last year’s world championships. The Russian-dominated body — which has faced years of clashes with the IOC — has refused to provide any information about the tests.

Algeria’s national boxing federation is still an IBA member.

Khelif is from rural northwestern Algeria, and she grew up playing soccer until she fell in love with boxing. Overcoming her father’s initial objections, she traveled 10 kilometers (about 6 miles) by bus to train for fights in a neighboring town.

After reaching the sport’s top level in her late teens, she struggled early in her career before reaching an elite level. Khelif has been a solid if unspectacular, international competitor for six years, and she lost to eventual gold medalist Kellie Harrington of Ireland at the Tokyo Olympics.

Khelif’s next bout in Paris is against Janjaem Suwannapheng of Thailand. If Khelif wins again, she will fight for a gold medal on Friday.

“Yes, this issue involves the dignity and honor of every woman and female,” she told an Algerian broadcaster in brief remarks Sunday after beating Hamori. “The Arab population has known me for years and has seen me box in the IBA that wronged me (and) treated me unfairly, but I have God on my side.”

He doesn’t lack confidence. Noah Lyles has ICON tattooed on his torso and doesn’t hold back when revealing his goals for 2024. “We’re going after everything,” the sprinter says, his voice dripping with self-assurance. “We’re going after the triple. Going after the world record, too. I know I can do this.”

That triple, which he accomplished at the 2023 World Championships in Budapest, is winning gold in the 100-meter, 200-meter, and 4x100-meter relay. Lyles’s feet move him faster than most folks on the planet. His quads have carried him 100 meters in 9.83 seconds and 200 meters in 19.31 seconds. The latter is an American record while the former was the world’s best in 2023. His hamstrings and calves have produced five Diamond League titles and six World Championship victories.

The five-foot-eleven 26-year-old will be chasing lightning at the 2024 Olympics in Paris, sprinting for the rarefied air of Jesse Owens, Carl Lewis, and Usain Bolt—icons who completed the triple on track and field’s grandest stage. Lyles craves that company and caused a stir by announcing on Instagram recently that he would run 9.65 in the 100 meters and 19.10 in the 200. That bodacious 0.21-second drop in the 200 would actually be just over the length of a stride for him—an additional 8.5 feet. (His stride is 7.74 feet.)

The numbers may sound like technobabble, but Lyles nerds out over the minutiae of muscle. “I’m a student of my craft,” he says.

Though he is the child of two collegiate sprinters, he doesn’t rely on genetics alone, training with intensity and focus. In-season work zones in on starts, acceleration, and feeling comfortable at top-end speed. Off-season, the backbone of his training is foundational leg work: the glute/ham machine, back and front squats, leg presses, and single-leg Romanian deadlifts. Before running, he does glute and calf activation drills with a physiotherapist who regularly flies in from Australia. Lyles also gets massages weekly, and a chiropractor tends to him every other week. Normatec leg-compression sleeves and the hot tub are consistent parts of his self-care as well. “If I don’t work on each individual piece to the fullest ability, I leave variables out,” he says. “And I want constants.”

One constant that challenges him is his start—the weakest part of his sprint game. A fast start could help him overtake Bolt’s record. Lyles’s biomechanist, Ralph Mann, uses force plates and slow-motion video to help perfect his form. Mann hones Lyles’s ankle angles so the 300 pounds of force he puts into the blocks propels him forward. Mann wants the physics of Lyles’s horizontal forces optimized in the first two steps out of the blocks. Tauter angle tilts combined with a proper center of gravity could generate potentially record-breaking speed.

Meanwhile, his physiotherapist gets granular—“into the extremely minute details,” Lyles says, referring to an asymmetry found in his starts. While the muscles around his left ankle and calf fire, pushing his foot into the block to drive him forward, his right teres minor—part of the shoulder’s rotator cuff—should also fire, pulling his right elbow and arm behind him, matching the left leg. But that doesn’t always happen—yet.

Intricacies rule Lyles’s training. “Why was one start better than another?” he asks. “Was it actually good or was it just me being fast on that day? I need to know all the variables.” Everything for speed.

This story originally appeared in the January/February 2024 issue of Men's Health.

To learn more about all the Olympic and Paralympic hopefuls, visit TeamUSA.com. Watch the Paris Olympics and Paralympics this summer on NBC and Peacock.

Thomas Ceccon's putting his bed where his mouth is ... lying on a blanket and catching a few winks after publicly slamming the Olympic Village.

The Italian swimmer was filmed taking a nap outside in a post from Saudi Arabian rower Husein Alireza ... fully stretched underneath a park bench, backpack down as a pillow.

Alireza wrote, "Rest today, conquer tomorrow," on the post ... and, it's getting a ton of circulation online -- mainly 'cause the dude publicly trashed conditions in the village.

Ceccon took home medals in his first two races -- winning gold in the men's 100m backstroke and bronze in the men's 4x100m freestyle relay -- but, he failed to qualify for the final in the men's 200m backstroke.

After his brutal defeat, Ceccon vented his frustration to the press ... claiming there's no air conditioning, the food's inadequate, etc. -- all complaints fans of the Olympics have heard from other athletes this summer.

But, many athletes are gutting through the conditions ... while Ceccon seems to be choosing greener pastures to nap on.

BTW ... this pic was posted Saturday -- and, Ceccon ended up missing out on the final in another relay event with the Italian team on the same day, so not sure how much the nap really helped.

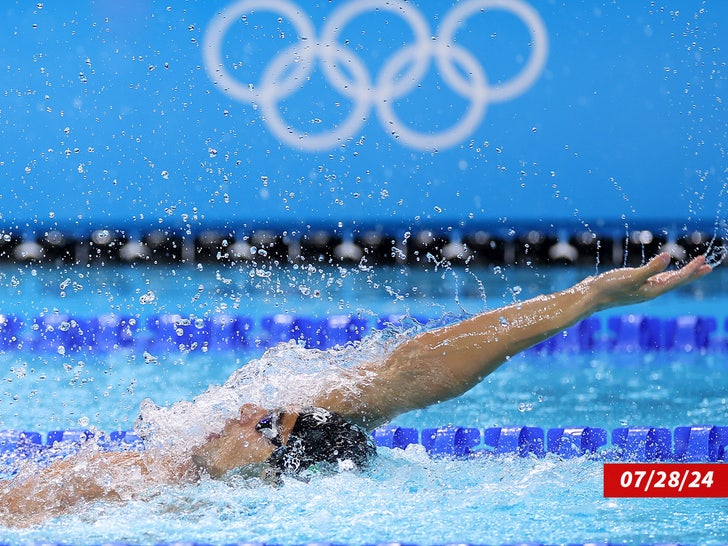

The final night of swimming at the Paris Olympics stirred a wide range of emotions for an American team that no longer rules the world.

A world record from Bobby Finke.

Elation.

A historic loss that reignited gripes about Chinese doping.

Stunning.

Finally, another world record for the women’s 4x100-meter medley relay team to edge out rival Australia for the top spot in the gold-medal table.

Whew!

“Just an awesome way to cap off the meet,” said Lilly King of the winning relay team, who joined her teammates in strolling around the deck holding up the stars and stripes as the crowd filed out of La Defense Arena.

Finke set his new standard in the 1,500 freestyle before the American women closed a thrilling nine days of swimming in style.

The U.S. finished with eight gold medals to top Australia, which won seven events. Still, it was the lowest victory total for the Americans since the 1988 Seoul Games, when they were beaten by a doping-tainted East German program.

They finished with 28 medals overall, two shy of their total three years ago in Tokyo. In all, 13 countries won at least one gold — French star Léon Marchand was essentially a country unto himself — and 19 teams made the medal podium.

After a bevy of disappointing performances by some of its biggest names, the U.S. team was very much aware of its gold-medal battle with the Aussies.

“I knew Bobby had tied it up,” King said. “Bobby’s swim was electric. That was amazing. He definitely got my energy going for the relay. I was pumped to hopefully assert that lead and get the gold.”

That’s just what she did.

King, whose third Olympics will be her last, made up for a disappointing showing in her individual events by powering to the lead in the breaststroke segment.

Then it was Gretchen Walsh and Torri Huske, two of the biggest U.S. stars at these games, bringing it home in 3 minutes, 49.63 seconds to break the record of 3:50.40 set by the U.S. at the 2019 world championships.

Regan Smith led off in the backstroke leg, earning a relay gold for the second night in a row after starting her Olympic career with five silvers and a bronze.

Australia, the defending Olympic champion, took the silver this time in 3:53.11. The bronze went to China in 3:53.23.

Four world records were set during the meet, three of them by the U.S.

Historic loss for the Americans

China stunningly won the gold in the men’s 4x100 medley relay, ending the American run of dominance that stretched back to the introduction of the event at the 1960 Rome Games.

The only time the U.S. didn’t win gold was in 1980 when it boycotted the Moscow Games.

The winning team included Qin Haiyang and Sun Jiajun, who were both among the nearly two dozen swimmers who tested positive for a banned substance before the Tokyo Games but were allowed to compete. The result stirred more hard feelings from other nations that felt the Chinese might have gotten away with cheating.

The real star of the Chinese team was Pan Zhanle, who had previously set a world record while winning the 100 free and powered away from American Hunter Armstrong on the anchor leg to touch in 3:27.46.

The Americans were left with the silver in 3:28.01, with France taking bronze in 3:28.38 to give Marchand his fifth medal of the games — four of them individual golds.

British star Adam Peaty, whose team barely missed out on a medal by finishing fourth, blasted a system that allowed the Chinese swimmers to compete at the Olympics.

“If you touch and you know you’re cheating, you’re not winning, right?” Peaty said. “As an honorable person, I mean, you should be out of the sport, but we know sport isn’t that simple.”

Peaty noted that after the initial revelations, additional reports surfaced of more positive tests in the Chinese program that went unpunished.

“I think we’ve got our faith in the system, but we also don’t,” he said. “Whoever’s in the race, I expect in my head that it has to be fair for them to be there. We did our best job as a team to do that, and it may have been (worthy of) a bronze. Who knows?”

Caeleb Dressel, who swam the butterfly leg for the Americans, said before the Olympics that he didn’t have faith in the World Anti-Doping Agency or his sport’s governing body, World Aquatics.

With a silver around his neck, he seemed resigned to the belief that nothing would change.

“I don’t work for WADA,” Dressel said. “There’s nothing I can do.”

Finke’s world record

Finke was under record pace the entire race and really turned it on coming to the finish. He touched in 14:30.67 to break the record of 14.31.02 set by China’s Sun Yang at the 2012 London Games.

The silver went to Italy’s Gregorio Paltrinieri in 14.34.55, while race favorite Daniel Wiffen of Ireland couldn’t follow up his triumph in the 800 freestyle. He was never a factor and settled for the bronze in 14:39.63, barely holding off Hungary’s David Bethlehem for the final spot on the podium.

Finke became only the fourth swimmer to defend the men’s title in the longest event at the pool, and the first since Australia’s Grant Hackett in 2004.

“I really wanted to get on top of the podium again and I hear the anthem all over again like I did for the first time in Tokyo,” said Finke, who swept the 800 and 1,500 three years ago.

This time, a gold in the 1,500 to go with a silver in the 800 felt pretty good, too.

“It was a dream,” he said.

Swedish gold in the women’s 50 free

Sarah Sjöström of Sweden claimed her second gold medal of the Paris Olympics, furiously dashing from one end of the pool to the other to easily claim the 50 freestyle title.

The 30-year-old Sjöström, competing in her fifth Summer Games, had already won the 100 free — an event in which she holds the world record but only decided to swim at the urging of her coach.

She was more surprised than anyone with that victory, which had her overflowing with confidence heading into the 50 free.

Sjöström touched 23.71, just shy of the world record of 23.61 she set at the 2023 world championships in Fukuoka, Japan. In a race that’s usually decided by mere hundredths of a second, the Swedish star turned this into a relative blowout. She was fastest off the block and clearly in control by the midway point of the single lap, where the swimmers don’t even bother coming up for air.

Meg Harris of Australia took the silver in 23.97, while the bronze went to China’s Zhang Yufei in 24.20. For Zhang, another of the swimmers implicated in the Chinese doping scandal, it was her fourth bronze of the games to go with a silver.

Walsh, in her first swim of a busy night, just missed out on a medal in 24.21.

It was a night for war-torn Ukraine to rejoice.

Thousands of Ukrainians watched on YouTube as high jumper Yaroslava Mahuchikh won gold for the country she was forced to flee, then celebrated with two teammates who also medaled at the Paris Olympics on Sunday.

Iryna Gerashchenko shared bronze in the high jump and Mykhaylo Kokhan then claimed a bronze in the hammer throw, too — doubling Ukraine’s Olympic medal haul from three to six in about an hour.

“Medals are very important for Ukraine because the people are having a very happy time, and they can cheer us and they can celebrate this with us and not think about the war for one day,” Kokhan said.

Mahuchikh, who left her home due to the war with Russia, earned Ukraine’s first individual gold of these Summer Games, following a victory in women’s team saber fencing on Saturday.

She is from Dnipro, a city of nearly 1 million located only about 100 kilometers (60 miles) from the front lines of the war. When Russia invaded, she piled as much as she could into her car and left town quickly. On her way out, she heard gunfire and could, at times, see shells raining down miles away.

The next time she returns, it will be as an Olympic champion.

Once the medals were assured, Mahuchikh and Gerashchenko ran down the track waving Ukrainian flags, prompting a standing ovation at the Stade de France.

Then, when the two high jumpers were given special permission to run over and embrace Kokhan, all three Ukrainian medalists posed together with their blue and yellow flags.

It wasn’t all about celebrating, though. Mahuchikh also recalled the “almost 500 sportsman (who) died in this war.

“They will never compete. They will never celebrate. They will never feel this atmosphere,” she said, adding that her gold medal is “really for all of them.”

Mahuchikh succeeds Tokyo gold medalist Maria Lasitskene, a Russian who — along with everyone else from her country — has been banned from track and field’s international events since the country invaded Ukraine.

Russian rockets and missiles constantly knock out Ukraine’s power grid. But Gerashchenko said that the electricity was working on Sunday,

“Today we have internet, we have light, and on the YouTube channel, around 160,000 people (watched) online,” she said.

Mahuchikh cleared 2.00 meters to finish ahead of Nicola Olyslagers of Australia, who also cleared 2.00 but then failed all three of her attempts at 2.02.

Eleanor Patterson of Australia and Gerashchenko shared the bronze at 1.95.

Mahuchikh considered jumping again and could have tried to break the world record of 2.10 that she set less than a month ago in another Paris stadium. But then she stopped and started celebrating.

Mahuchikh was asked why she didn’t make any further attempts.

“Why not? I was the Olympic champion,” she said.

Mahuchikh also gained curiosity for the way she lies down and wraps herself up in a type of sleeping bag between jumps. She said it helps her relax: “Sometimes I can watch the clouds...not think about that I’m at a stadium.”

Mahuchikh claimed the first Olympic gold of her career, adding to the bronze she won in Tokyo. She also won gold at last year’s world championships.

“It’s all medals for our country, Ukraine, for our defenders,” she said. “Only thank(s) (to) them we have the opportunity to be here.”

The U.S. Women's Basketball team continued their dominance at the Paris Olympic Games with a convincing 87-68 victory over Germany, closing out Group play with an unblemished 3-0 record.

This win marks the team's 58th consecutive Olympic triumph, setting them up as the top seed for the knockout round starting Wednesday.

Jackie Young led the charge off the bench, scoring 19 points, while A'ja Wilson added 14 and Breanna Stewart contributed 13.

The Americans showcased their trademark balanced offense and stifling defense, forcing 23 turnovers and limiting Germany to just three offensive rebounds.

Germany, fresh off a victory over Belgium, managed to take an early lead, finishing the first quarter ahead 19-16.

However, Team USA responded with a 25-10 run in the second quarter, breaking the game wide open.

Despite occasional runs by Germany, the U.S. maintained control, pushing their lead to 23 points by the end of the third quarter.

Coach Cheryl Reeve's squad exhibited exemplary teamwork and defensive energy, with key contributions from Kelsey Plum and Young at the point of attack, and Wilson and Stewart dominating the pick-and-roll.

Napheesa Collier and Alyssa Thomas added to the defensive effort with active hands and relentless pressure.

Despite a slow start from beyond the arc, where the team made only three of its first 12 attempts, the Americans found their rhythm as the game progressed.

Young's five three-pointers off the bench and additional long-range shots from Kahleah Copper helped extend the lead.

Germany's Satou Sabally, a standout player for the WNBA's Dallas Wings, led her team with 15 points but struggled against the relentless U.S. defense.

The Americans limited their opponents to 43% shooting and have held their Olympic adversaries to just 40% overall in France.

As the U.S. team advances to the quarterfinals, their path to an eighth consecutive gold medal appears firmly within reach.

Their next game set for Wednesday in Paris will be against Nigeria at 3:30 pm ET, where the Americans are poised to continue their unprecedented winning streak and further solidify their dominance in Olympic basketball.

Scottie Scheffler was a model of calm and greatness as he delivered the greatest closing round of his career. The final two hours were about charges and collapses, a pure theater that ended Sunday with the Olympic gold medal fittingly draped around the neck of golf’s No. 1 player.

It was only when Scheffler stood on the top podium when the final few bars of the national anthem belted out across Le Golf National, that he lost control.

The medal dangling beneath his right hand fixed across his chest, Scheffler raised his left arm to cover the sobs.

Tears are nothing new for Scheffler. His latest trophy brought out his very best.

Four shots behind to start the final round, six shots behind early on the back nine, Scheffler birdied five of six holes down the stretch and matched the course record with a 9-under 62 for a one-shot victory over Tommy Fleetwood.

“It’s been a long week. It’s been a challenging week. I played some great golf today, and I’m proud to be going home with a medal,” Scheffler said. “These guys played tremendous golf and I think we should all be proud of the golf that we played this week.”

It was a show-stopper, the best of the three men’s competitions since golf returned to the Olympic program in 2016 before 30,000 spectators got their euros’ worth.

The remarkable surge by Scheffler, who shot 29 on the back nine. The relentless play of Fleetwood (66) and Hideki Matsuyama, who had birdie chances on the final six holes and had to settle for pars for a 65 to win the bronze.

And there was a stunning collapse by Jon Rahm, who saw a four-shot lead disappear in two holes and his hopes vanish with a double bogey; by Rory McIlroy, one shot behind until hitting a wedge into the water; and by Xander Schauffele, the PGA and British Open champion who had a chance to win another gold until playing a four-hole stretch in 4-over par.

Not to be overlooked was Victor Perez of France, who hit the opening tee shot on Thursday and came within one shot of a medal on Sunday. He should know the lyrics to “La Marseillaise” if he didn’t already. Fans serenaded him on just about every tee.

All of them had a chance during this thriller of a backnine.

In the end, it was Scheffler — of course — giving the best performance of his greatest year. Already a six-time winner on the PGA Tour this year, including his second Masters title, Scheffler added Olympic gold to an astonishing season with a round that kept the sellout crowd on edge for a wild conclusion.

He set an Olympic record for 72 holes at 19-under 265.

Scheffler becomes the second straight American to win gold in men’s golf, following Schauffele in the Tokyo Games.

The only downer was Scheffler winning while on the practice range, mentally spent while preparing for a playoff that didn’t happen when Fleetwood missed the 18th green well to the left and his 100-foot pitch just missed the hole.

It was all such a blur that Scheffler didn’t even know where he stood.

“I saw that Rahm had gotten to 20-under, and so I kind of changed a little bit mentally to just really try to do my best to move my way up the leaderboard, and at one point I didn’t even really know if I was in contention or not,” Scheffler said.

“I just tried to do my best to make some birdies and start moving up and maybe get a medal or something like that just because Jon is such a great player.”

When he finally got a look at a leaderboard behind the 16th green, Scheffler was in the fairway on the par-4 15th and hit a wedge to a foot. That got him within one. Then came his tee shot to 8 feet for birdie on the par-3 17th. And the winner turned out to be an 8-iron he gouged out of the rough to 18 feet for a fourth straight birdie and his first lead of the week.

“He’s been piling up trophies left and right and he keeps moving away from what is the pack of people chasing him in the world,” Schauffele said. “When I take my competitive hat off and put my USA patriot hat on, I’m very happy that we won another gold medal.”

McIlroy, who ended his 10th straight year without a major, entered the mix when he began the back nine with five straight birdies. He was one off the lead, in the middle of the 15th fairway with a wedge in his hand.

“Missed my spot by nearly 3 or 4 yards and that ended up costing me a medal,” he said.

But he came away with a deeper appreciation of the Olympics, especially in the three years of rising prize money to fend off the rival LIV Golf league funded by Saudi riches.

“I still think that the Ryder Cup is the best tournament that we have in our game, pure competition, and I think this has the potential to be right up there with it,” McIlroy said. “I think with how much of a (expletive) show the game of golf is right now and you think about the two tournaments that might be the purest form of competition in our sport, we don’t play for money in it.”

“It speaks volumes for what’s important in sports,” he said. “I think every single player this week has had an amazing experience.”

That starts with Scheffler, who showed sheer brilliance with his best score of the year, a 62 that matched the best closing round of his career. He opened with three straight birdies to get his name on the board. He had a pair of 12-foot birdies early on the back nine.

And then Scheffler began to soar until he got on the podium and sobbed. He won The Players Championship with a five-shot comeback in March, another Masters title in April, and four signature events on the PGA Tour against the strongest fields.

And now an Olympic gold medal.

“It was just very emotional being up there on stage there as the flag is being raised and sitting there singing the national anthem,” he said. “That’s definitely one I’ll remember for a long time.”

Americans Kelly Cheng and Sara Hughes lost a set for the first time in the Paris Olympics beach volleyball tournament.

All that did was fire them up.

“When we bring the fire, the energy, the passion, we play better. So, we want to bring that all the time,” Hughes said after beating Italy 21-18, 17-21, 15-12 on Sunday. “Kelly and I really fight to stay in that present moment, and that really helps our team.”

Hughes and Cheng, the defending world champions, trailed 17-16 in the first set before scoring five of the next six points. In the second, Italians Marta Menegatti and Valentia Gottardi scored five points in a row to pull away after an 8-8 tie.

In the third, the Italians erased an early six-point deficit and closed to 12-11. Cheng and Hughes, pumping their fists and kicking up sand in celebration like they hadn’t in their previous matches, made it 14-11 and then clinched their second match point.

“It’s not pool play anymore,” Cheng said. “You lose and you’re out. So for sure, there are emotions. It’s something we’ve been working for for a long time. So, yeah, the points, you feel them, for sure.”

The Americans’ next match is against Switzerland’s Tanja Hueberli and Nina Brunner, who beat Spain earlier Sunday.

In the other night match, Brazil’s Evandro and Arthur eliminated the Dutch team of Matthew Immers and Steven van de Velde. Van de Velde was convicted of raping a 12-year-old British girl in 2016.

Defending world champions David Schweiner and Ondrej Perusic from Czechia fell to the other Dutch team earlier in the round of 16.

“We knew that if we can play well, we can beat them,” said Holland’s Yorick de Groot. “But for the last four matches they beat us, and we’ve been struggling against them.”

The Netherlands will play Germany in the quarterfinals.

“The last time we played them was also the first time we beat them, so that was a good feeling for us and we’re going to take a lot of that into the next game,” said his teammate, Stefan Boermans. “They will also definitely see the footage back from that match and will adjust.”

The Czechs played in Tokyo but didn’t make it out of the group stage.

“To be a bit positive, it was a way, way better experience than Tokyo. Finally, we experienced real Olympics,” Schweiner said. “It was an unbelievable venue. The city, the country, and the whole of Europe are really living for the Olympics. It’s amazing and we’re feeling really privileged to go through it, to be here.”

Sweden, which arrived in Paris as the No. 1 team in the world, went just 1-2 in the group stage to land a tough Cuban team in the round of 16. The Swedes won the first set 21-11 but then fell in an extended second, 28-26, before clinching with a 15-11 result in the decisive third set.

“We only said that we have to go for it,” 22-year-old first-time Olympian David Ahman said. “’ It’s going to be super tough, but we have to take every chance and believe in ourselves. Let’s go for it.’ And that’s what we did.”

In earlier women’s matches, Australia defeated the Brazilian team of Carolina and Barbara 2-0. Switzerland’s two women’s teams both won in straight sets: Zoe Verge-Depre and Esmee Boebner beat China, and Tanja Hueberli and Nina Brunner knocked out four-time Olympian Liliana Fernandez Steiner and her partner, Paula Soria Gutierrez, of Spain.

.webp)

.webp)

.webp)

.webp)

.webp)

.webp)

.webp)

.webp)

.webp)