If you receive your paychecks every two weeks, August might bring a pleasant financial surprise. For employees on a bi-weekly pay schedule, each year includes "two months where you receive three paychecks instead of the usual two." August might be one of these "three-paycheck months," depending on your specific pay schedule, as explained by CNBC. This occurs because there are 26 pay periods in a year (since 52 weeks divided by 2 equals 26), resulting in two months being "three-paycheck months."

The timing of this "extra" paycheck depends on when you receive your first paycheck of 2024. If your first paycheck came on January 5th, your three paycheck months would be March and August. However, if your first paycheck was on January 12th, your three paycheck months would fall in May and November.

While the temptation to splurge is common when your bank account appears fuller, that third paycheck presents an excellent chance for financial growth. Here are some ways to capitalize on a three-paycheck month:

1. **Boost Your Savings**: A wise choice for the extra cash is to contribute it to your emergency savings fund. This fund should be easily accessible for emergencies like job loss or significant car repairs. Experts suggest maintaining enough to cover three to six months of living expenses.

2. **Reduce High-Interest Debt**: Another smart move is to use the additional paycheck to pay down high-interest debt, particularly revolving credit card balances, which can carry interest rates over 20%. Doing so can save you significantly on interest costs.

3. **Enhance Retirement Contributions**: Consider putting the extra money into your retirement savings. You could temporarily increase your 401(k) contributions, or ideally, make a permanent contribution increase for the year, allowing this extra paycheck to assist with other expenses.

4. **Plan for Future Expenses**: Use the extra paycheck to progress towards other savings goals, such as a home down payment, college education for your child, or even an upcoming vacation. It's also okay to enjoy some of it with friends or family responsibly.

Whether you choose to save, pay off debt, invest in your future, or simply enjoy a bit, make thoughtful use of your extra paycheck to improve your financial situation.

As the U.S. economy began recovering from coronavirus-related shortages and shutdowns, consumer prices surged faster than they had in more than four decades. Many Americans currently see inflation as one of the nation’s top problems.

The government gauges inflation mainly by looking at the prices of a “market basket” of more than 200 goods and services and evaluating how they’ve changed over time. Several inflation measures are based on this price data, but the most widely cited is the Consumer Price Index for All Urban Consumers (CPI-U). Since the start of 2020, that measure topped out at 9.1% in June 2022 – the fastest year-over-year increase since November 1981.

Since the June 2022 peak, inflation has abated considerably. The CPI-U in June 2024 was just 3.0%, closer to the Federal Reserve’s 2% inflation target. That’s led to increased speculation that the Fed may start cutting interest rates soon.

But that doesn’t necessarily mean prices are going back down – just that they’re rising more slowly than they had been. Most things cost considerably more than they did before the COVID-19 pandemic. And the focus on the topline number can obscure the reality that inflation for individual items can be considerably above – or below – the “official” rate.

With all that in mind, we wanted to take a closer look at the CPI-U, and at the 200-plus products and services that go into that headline inflation number.

\Which goods and services have gotten more – or less – expensive in recent years?

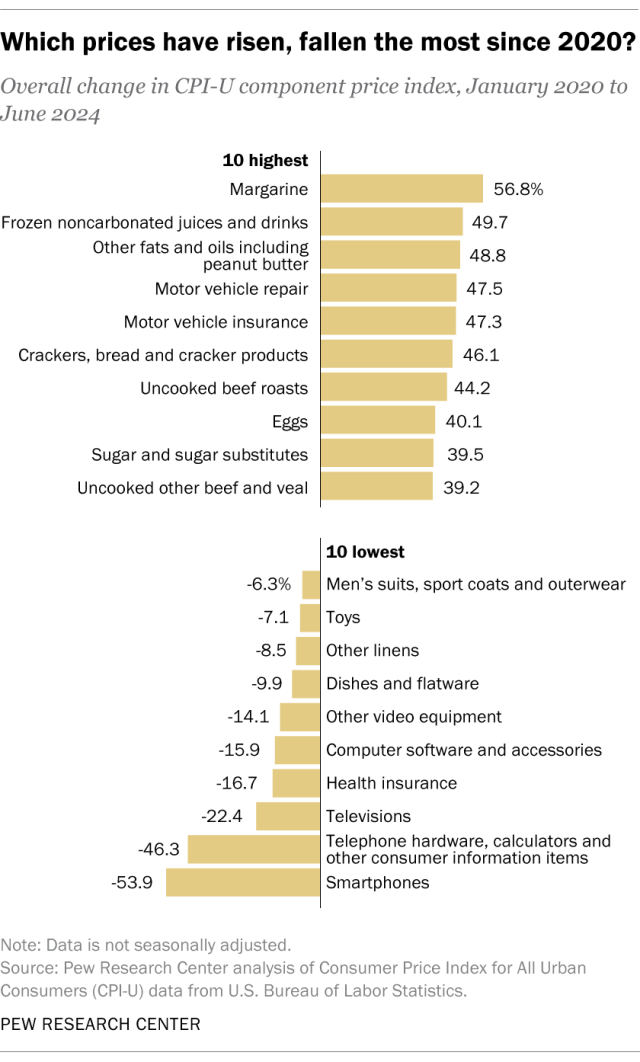

Overall, the June 2024 CPI-U was 21.8% above its level in January 2020, before the pandemic really began to hit the United States. But the costs of many products and services have risen much more than that.

Topping the list: margarine, which as of June is 56.8% pricier than in January 2020. Other notable increases include motor vehicle repair services (up 47.5%), motor vehicle insurance (47.3%) and veterinarian services (35.6%).

On the other hand, some goods and services cost less now than before the pandemic. For example, men’s suits, sport coats, and outerwear are 6.3% cheaper than in January 2020. And dishes and flatware are down 9.9%.

Many of the items with the biggest price declines are related to computers, smartphones, or other technologies. In these and other cases, the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) – which puts together the CPI-U and related indices – adjusts the raw price data it collects to account for product improvements or other changes in quality over time.

In 2007, for example, the first-generation iPhone from Apple cost $499 (or $599 for the 8-gigabyte version) and came without many features that users today take for granted. Today, the 128-gigabyte base version of the iPhone 15, which is far more powerful and functional, retails for $799. Other smartphones have seen similar quality leaps over time.

The price index for smartphones has fallen 53.9% between January 2020 and June 2024. That essentially means that buying a smartphone today with the functionality that was typical in early 2020 would cost you less than half what it would have then.

What items carry the most weight in the CPI-U?

The hundreds of goods and services in the CPI-U aren’t all given equal weight when calculating the index. Instead, the BLS weights each item to reflect its share of overall consumer purchases.

The biggest item in the CPI-U, accounting for about a quarter of the entire index as of May 2024, is the “owner’s equivalent rent of a primary residence” (OER). This arcane-sounding term basically estimates how much it would cost to rent out an owned home. It’s an attempt to separate a house’s value as shelter (which is treated as a service in the CPI-U) from its value as an investment (the increase in its market value over time), since investments aren’t included in the CPI-U.

OER inflation peaked at 8.1% in spring 2023 and still came in at 5.4% in June 2024. Overall, OER prices are 23.8% above their January 2020 level – just a hair below rental inflation, which is up 24.0%. Rental prices are the second-biggest factor in the CPI-U at about 7.6% of the total index.

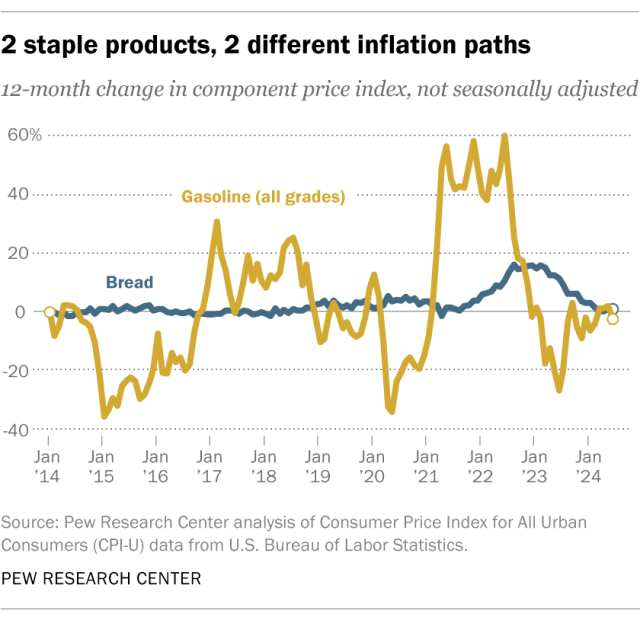

For many items, prices tend to rise or fall gradually, or at best, level off. Bread prices, for instance, seldom changed by more than a few percentage points annually from 2014 until early 2020 – though they jumped in 2022. But some items are far more volatile, with unpredictable surges and steep declines.

Gasoline, the third-biggest contributor to the CPI-U at about 3.6% of the index, is a prime example. Pump prices fluctuate based on the time of year, geopolitical events, refinery operations, and a host of other factors.

Overall, the price index for all grades of gasoline was 35.9% higher in June 2024 than it was in January 2020. But that hides considerable volatility. From January 2020 to June 2022, gas prices nearly doubled (an 89.5% increase), but since then, they’ve fallen 28.3%. In fact, for all of its ups and downs, the average nationwide gas price at the end of July 2024 ($3.598 a gallon) was about what it was in early August 2014 ($3.595), according to data from the U.S. Energy Information Administration.

Which items have seen particularly sharp price spikes since 2020?

The 89.5% run-up on gasoline of all grades was almost the biggest of the pandemic period. But the price index for fuel oils (such as home heating oil) rose slightly more – 91.0% – between January 2020 and June 2022 before dropping. As of this June, fuel oil prices were 22.2% above their January 2020 levels.

The product with the sharpest (but short-lived) price spike over the past few years has been the humble egg. Egg prices peaked in January 2023 at 94.0% above the January 2020 baseline. Even though prices have fallen since eggs still are about 40.1% more expensive than they were before the pandemic.

The era of hefty pay increases is over, and companies are already making plans to trim raises again next year.

The shrinking raises are the latest sign—alongside last week’s lackluster jobs report—that workers have lost much of the leverage they’ve had with bosses in the past few years. With hiring now slowing sharply, employers are controlling payroll costs by cutting or freezing bonuses, and doling out fewer and smaller merit increases, business leaders and compensation consultants say.

With hiring now slowing sharply, employers are controlling payroll costs by cutting or freezing bonuses, doling out fewer and smaller merit increases. (Getty Images/Photo illustration/FOX News Digital / Fox News)

Some companies are also trying to fill roles as they open in lower-cost cities, paying smaller salaries than what the previous person was making.

Meanwhile, fewer workers are getting pay bumps from switching jobs than they did late last year, new data show.

Among 1,900 U.S. companies polled in the second quarter, nearly half said they had downsized their budgets for salary increases this year. That has lowered the median raise to 4.1% this year from 4.5% in 2023. They plan to spend even less next year, projecting a median raise of 3.9% in 2025, according to employer-advisory firm WTW, which conducted the survey.

Ellen Teeter, 23 years old, said she’d hoped for more than the 1.5% raise she received this year.

"I was underwhelmed," said the bank operations analyst in Charlotte, N.C.

When she joined her company a year ago, she received a 10% signing bonus and was told this year’s raises would range from none at all to 10%. She wasn’t the only one with an increase on the low end. Most co-workers she spoke with also received between 1% and 2%, and one received 4%.

For now, the disappointing raise isn’t enough to leave, Teeter said, since she expects to be able to move to a higher-level position in the next year. If she doesn’t, she’ll start looking for other jobs: "I’d like to make more money and do more work that matters."

Plenty of job candidates

Raises remain high from a historical perspective, but they’re hardly the generous boosts companies doled out to keep workers two to three years ago. Tech companies that boomed during the pandemic snapped up workers with lofty pay offers even before having anything for them to do and, across the economy, employers tried to prevent staffers from leaving with outsize pay hikes.

Many companies have reduced their budgets for salary increases this year. (iStock / iStock)

As that largess has shriveled, new hires appear to be bearing the brunt. In the second quarter, 58% of people hired to jobs in recent months got more pay with the switch than they were earning previously. That’s down from 70% in the fourth quarter of last year, according to a survey of 1,500 recent hires by jobs platform ZipRecruiter. About one in seven received signing bonuses, compared with nearly one in three in the fourth quarter.

Some companies are making a concerted effort to reset pay rates. At agriculture giant Syngenta, CEO Jeff Rowe said executives are more closely scrutinizing where to add new jobs or replace existing roles once people leave, part of a larger corporate effort to reduce costs and find efficiencies.

That means hiring talent in cities with cheaper salary costs, such as Manchester, England, or Budapest, as opposed to higher-cost locations. The goal is to take advantage of "geographic arbitrage," Rowe said.

A cooling job market also means managers have their pick of hires, which is helping to rein in pay, said Julia Pollak, ZipRecruiter’s chief economist. In the ZipRecruiter survey, a quarter of recent hires said they had felt emboldened to try to negotiate their salary offers. That’s down from 43% in the first quarter of the year, suggesting job seekers are well aware employers have other qualified candidates to choose from.

An even smaller share of them—85%—was actually successful in negotiating a better offer, compared with more than 90% last year.

The cooling job market is contributing to companies reining in salary offers for new hires. (iStock / iStock)

"You don’t need to deliberately reset pay," Pollak said. "You just have more applicants prepared to accept your first offer."

(Don’t bet on an outside job offer to pressure managers to pay up: Roughly 16% of new hires in the survey said their employer countered an offer when they announced their departure, down sharply from the start of the year.)

Pay rates for new hires across industries are 7% lower than they were for new recruits for the same roles in 2022, according to new data from Gusto, a payroll and benefits software company serving more than 300,000 small and midsize businesses. Some of the biggest drops have been in white-collar roles, including in finance, where new-hire pay rates have fallen 9.2% since last year.

Shallower bonus pools

Curtailing raises by even a few tenths of a percentage point can save hundreds of millions of dollars in annual payroll costs for big companies, said Lori Wisper, a managing director at WTW.

The challenge: Reserving enough to reward high performers and keep them motivated to stay.

"I’ve been saying to my clients, ‘Use the money wisely. Don’t spread the peanut butter around where everyone gets the same,’" she said. That means being more discriminating with merit raises and bonus amounts.

Jim Chung, a compliance specialist with a financial services company in New York, expected to get a bigger bonus this year, but it stayed the same—roughly 15% of his salary. With inflation, he said, it feels like he earned a smaller bonus than a year or two ago.

Still, he fared better than many colleagues who didn’t receive any bonus this year, and a bump in his base salary helped, too.

A flat bonus "wouldn’t be the sole factor for me to look elsewhere," he said.