Alaska Airlines was the first domestic carrier to sell tickets online, in 1995, and the first to use GPS to guide its airplanes in 1996. Now it wants to be the first to implement a new vision for a passenger jet in a bid to slash emissions.

Alaska’s just-announced investment in JetZero, a Long Beach, California-based company seeking to pioneer the blended-wing-body airliner, is part of the company’s long-term innovation strategy. The undisclosed amount of funding fits into a larger vision to help the carrier meet its goal of net-zero carbon emissions by 2040.

“We do not want to be the cigarette industry in 20 years, where we’re regulated out of existence because people say it’s so bad to fly in an airplane,” said Pasha Saleh, head of corporate development at Alaska Airlines. “We want to make sure we’re developing multiple solutions but actually driving each of them forward.”

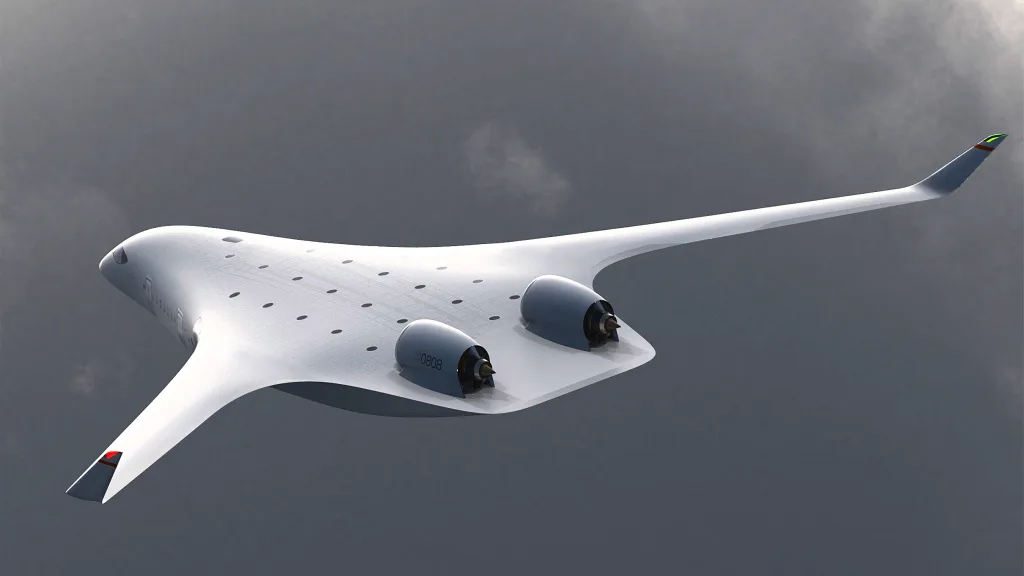

JetZero’s innovation, the blended-wing-body (BWB) aircraft, offers a more sweeping shape and aesthetic compared to the traditional tube-and-wing airliner that currently dominates commercial flight. The BWB concept boasts a more triangular, stretch design—where the cabin and wing blend together—creating more aerodynamic efficiency and lift. This allows the plane to fly higher, at around 45,000 feet, which further cuts wind resistance. Factor in the change in materials and construction, with bolted metal and composites, swapped out for lighter, stitched carbon fiber, and a BWB jet can carry hundreds of passengers with half the fuel, a huge cost savings and environmental benefit.

“JetZero is one of these rare situations where everything gets better,” Saleh said. “It’s so rare in engineering where you come across a solution where there are so few trade-offs, if any, to be made.”

JetZero’s CTO, Mark Page, has worked on and refined the BWB idea for decades, even creating prototypes for NASA in the 1990s and designing drones that utilized the body shape in the 2000s. Despite decades of research from industry players, including NASA and major aircraft makers, the BWB hasn’t been built for commercial use, in part because carriers and manufacturers haven’t had a financial motivation. According to JetZero CEO Tom O’Leary, the industry’s take for decades has essentially been, why innovate when there’s a backup of jet orders and fuel costs are low?

What’s moved the concept closer to reality is both new and improved technology—namely better computer modeling for testing and advances in carbon fiber materials—and the pressing business case for cutting emissions. The Air Force has even invested in JetZero to help develop a BWB cargo plane; roughly 60% of the branch’s annual jet fuel spend comes from cargo planes.

Airlines like Alaska face a compounding set of challenges around emissions and flight technology. Airplanes account for 2.5% of global emissions, a figure set to only increase in coming years, which is leading to more scrutiny and regulations. Carriers, meanwhile, face the rising cost of jet fuel, which accounts for about 20% of the cost of flying (fuel prices are up 8% since 2019 alone). At the same time, the clock is running out to create a truly net-zero aviation alternative; the International Council on Clean Climate says that for the industry to meet its global ambition of net-zero flying by 2050, new planes entering service need to be net zero starting in 2035.

The benefits of the JetZero model go beyond helping passengers cut their carbon footprint; in industry speak, the increased efficiency lowers the fuel burn per seat mile. JetZero’s headquarters sit inside a large hangar across from the Long Beach Airport. Within the hangar, a mock-up of the cabin has been laid out with working bins, foam mat seats, and cutouts of walls, ceilings, and windows. Bathrooms are all clustered in the back, reducing wait times in aisles, and a triangular service area toward the front of the aircraft can be modified to create space for serving and preparing more elaborate meals, and even setting up an in-flight bar.

Just strolling through the mock interior it’s immediately apparent how different this layout could be if carriers utilize the fuel and energy savings and resist the urge to value-engineer this new kind of airplane. Due to the wider fuselage, rows can fit more than 15 seats across, with high ceilings and seating broken up into different sections that feather out from the front cockpit. JetZero designers have even experimented with layouts that include an individual baggage bin for every seat.

Glen Noda, JetZero’s head of product design and an industry veteran who has helped create aircraft interiors for years, said there’s just nowhere left to go in terms of innovating the traditional commercial jet. The larger body of JetZero planes allows for less pressure to squeeze profits, and in doing so, passengers.

“The knee-jerk response for airlines is wanting to densify everything because that’s what you’ve done for 50 years, but that’s not what we need to do on this airline to be profitable,” Noda said.

Saleh said that Alaska is interested in the possibility for technological change and efficiency, as well as all the other benefits such a plane could bring, like making air travel more comfortable, affordable, and accessible.

The investment and partnership with JetZero fit into the carrier’s larger vision for innovation through Alaska Star Ventures, the company’s VC arm. Founded in 2021, this venture wing has already invested in several next-generation ideas for flight, including a hydrogen-powered plane and a glider system for short-haul flights between Hawaiian islands. In addition, Alaska has partnered with sustainable aviation fuel startup Gevo, though some critics argue the fuels are a “false solution” that amounts to greenwashing.

According to Saleh, airlines don’t have the skills and capabilities to gestate these kinds of research projects, so it makes more sense to invest in and collaborate with startups. The best of these potential ideas will get to market and scale more quickly if they’re developed with an industry partner, like Alaska, which can help incubate a new plane or technology so it immediately works within real-world constraints. Other airlines, namely JetBlue, have had venture arms, but Alaska wants to make sustainability the focus of its startup ambitions.

“We’re doing this because to get to a sustainable future for aviation, it’ll take ideas that either don’t exist today or currently only exist in a lab,” he said. “We want to be very active investors. We don’t want to place bets the way you would in a Las Vegas casino and hope one of them hits. We realize it’s going to take all of these things.”

The pathway for this partnership to truly take flight will require years of work, innovation, and regulatory approval from the Federal Aviation Administration, as well as clear communication and due diligence around safety; Alaska became embroiled in the current wave of aviation safety concerns when the door of a Boeing-made jet blew off mid-flight in early January. JetZero’s existing road map includes certification in 2027 and entering commercial flight in 2030. In April, the FAA cleared a smaller 1:8 scale JetZero demonstrator plane to begin test flights, which are taking place at an undisclosed site in the California desert.

The company is currently working on a full-scale model while scouting out potential manufacturing sites. By working with Alaska, the startup can help get its vision into commercial rotation.

“We want to deploy these theories into practice,” JetZero’s O’Leary Said. “People often say that’s a good theory, but it doesn’t work in practice. But that’s the definition of a good theory, that it does in fact work in practice.”

The US DoD plans a $235m investment into Blended Wing Body aircraft with Jetzero. The goal is a prototype by 2027.

— ToughSF (@ToughSf) September 18, 2023

The BWB concept is a century old and promises today a 30% decrease in drag plus additional lift over a regular tube-and-wing plane. https://t.co/uApAPJJwWg pic.twitter.com/tBd54exZRz