On Wednesday, the Federal Reserve lowered its benchmark interest rate by half a percentage point. The action will take the rate to between 4.75% and 5% immediately. The Fed also announced more cuts are likely before the end of the year.

The combination suggests the Fed is taking the threat of a slowdown to the American economy seriously. It’s about time — in fact, it’s long past time.

Many Americans are getting increasingly picky about their spending.

Yes, at first glance the U.S. economy, appears to be doing “basically fine,” as Powell put it in his press conference today. The stock market is booming, and retail sales and consumer confidence remain solid. But under the surface, signs of trouble are increasing.

Credit card debt has been rising over the past year. So, too, have credit card delinquencies, which are now at their highest rate since the 2008 financial crisis. Auto loan delinquencies are up as well. Unemployment, though still a relatively low 4.2%, is nearly half a percentage point higher than a year ago. Payroll growth is slowing, and the job market is stagnating, particularly for white-collar workers.

As a result, many Americans are, if not completely abandoning the YOLO attitudes of recent years, getting increasingly picky about their spending. While overall retail sales are inching higher, restaurant sales are flatlining, and the post-pandemic travel bonanza is slowing, with hotels reporting less demand from vacationers. Aside from Taylor Swift, musicians are struggling to draw crowds. Even Jennifer Lopez canceled a planned tour this summer in the face of flagging sales. Other acts, especially on the nostalgia circuit, joined forces, giving audiences two-for-one deals, seemingly to make it more likely they could fill up the seats. (Elvis Costello and Daryl Hall toured together this spring and summer. So did Rick Springfield and Richard Marx.)

That this would happen has all been clear for some time — the last of the savings built up over the pandemic ran out in March — but the Fed cavalierly prioritized its battle against inflation even as it became increasingly obvious that the battle against pandemic-era price increases and gouging is all but won. Last month’s consumer price index came in at an annual rate of 2.6%, just a tick higher than it was pre-pandemic. Gasoline prices average about $3.20 a gallon nationally, down 50 cents since April, and some experts think the national average could go below $3. Major retailers like Walmart and Target have dropped prices on thousands of items, so much so they’ve put pressure on traditionally lower-price-point dollar stores.

The Biden administration has already moved to take on corporate price gougers, and Vice President Kamala Harris says she will continue that effort if elected. Last month, the Justice Department sued software company RealPage, alleging its rent management software offered landlords a backdoor way to collude on rental prices.

This isn’t an attempt to throw the election. It’s something that should have been done months ago.

The inflation that’s hurting American families the most right now is high interest rates — and the Fed’s rate cut can do something about that. Credit card debt now comes with an average rate of well over 20%, while store-branded cards are at a record high with an average annual rate of 30.45%, according to a recently released study from Bankrate. The Fed’s move Wednesday should begin to bring these eye-popping rates down.

The same is true of housing costs: While the interest rate on mortgages is most closely tied to the yield on 10-year Treasury bonds — which are already coming down as inflation eases — that number is also often influenced by the benchmark rate. The new cut will almost certainly make it easier for millions of Americans to find new homes.

Please. This isn’t an attempt to throw the election. It’s something that should have been done months ago. Powell admitted as much, saying Fed officials “may have cut earlier” had they had the economic knowledge they have now in the summer.

As for Trump, always remember: He’s only out for one person — himself. That’s why he’s complaining both that interest rates should come down and that inflation is higher than ever in U.S. history (as someone who lived through the 1970s, he should know that’s a lie). The only purpose of this incoherent position is to argue for his election.

Since 1977, the Federal Reserve has had a dual mandate: to balance and maximize price stability with maximum employment. It’s finally back on both cases — and not a moment too soon.

The Fed reduced the federal funds rate to 4.75%-5.00% in its September meeting, down from 5.25%-5.50% previously. Markets had been split on whether the Fed would opt for its normal 25-basis-point cut or go with a 50-basis-point cut.

In the end, the Fed went with the larger cut of 50 basis points. But that doesn’t mean the Fed was trying to deliver a shock to the markets.

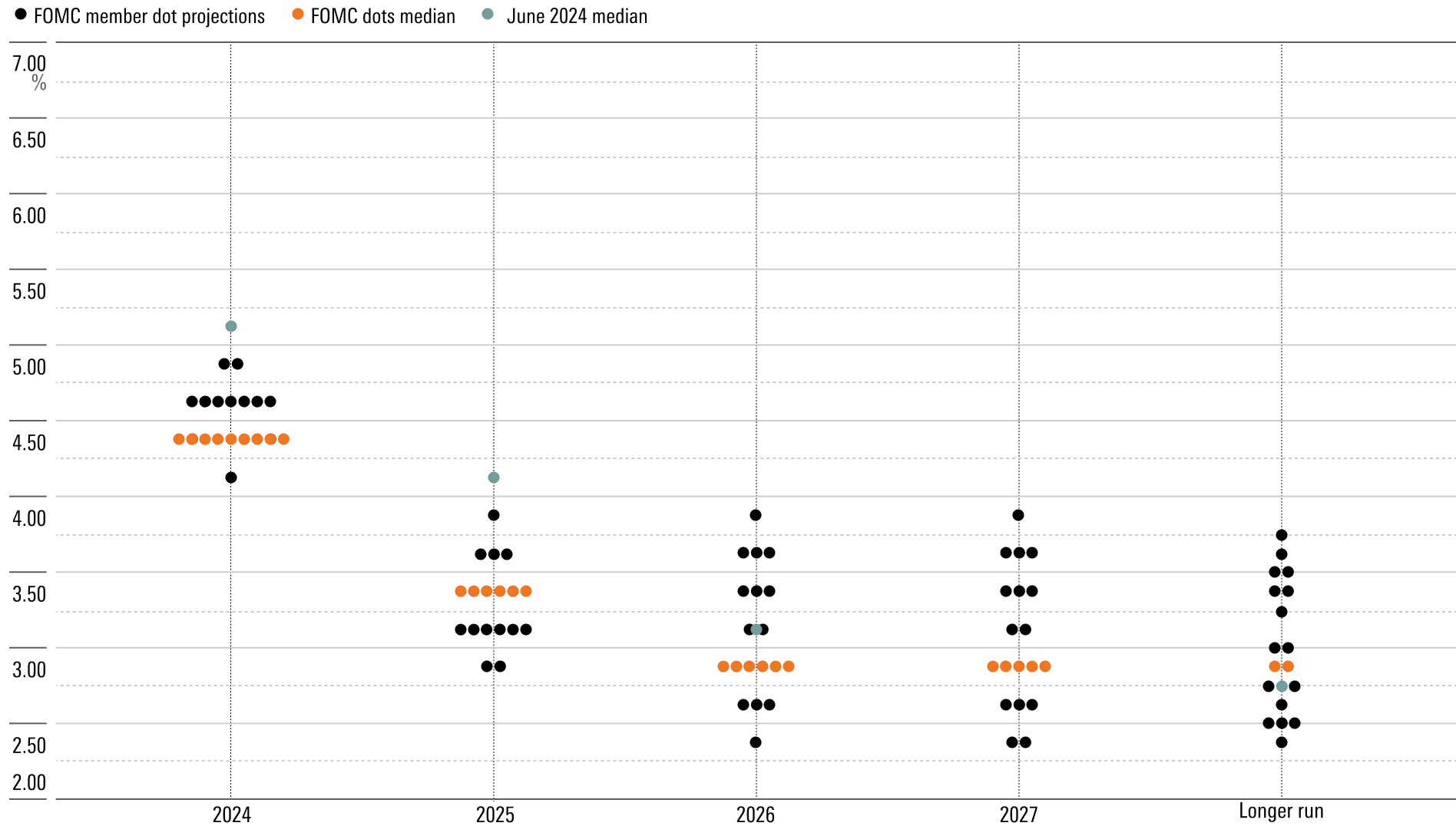

Indeed, the updated FOMC projections imply that the Fed is going to switch to a more gradual pace in future meetings, including cutting by 25 basis points in the final two meetings of 2024. Additionally, Fed projections call for a year-end 2025 federal funds rate of 3.25%-3.50%. While that’s a hefty reduction from prior projections of 4.00%-4.25% at end-2025, it’s a step above recent market-implied expectations of a 2.75%-3.00% federal-funds rate at end-2025.

In effect, the Fed is suggesting that the market has already baked in ample expectations of Fed rate cuts, and there’s no need (for now) for those expectations to fall further.

The Dot Plot: Federal-Funds Rate Target Level

Expectations for the federal funds rate are the primary driver of bond yields. As rate cut expectations have steepened, the two-year Treasury yield has dropped to 3.6% as of mid-September from 4.5% in late July 2024. The 10-year Treasury yield has also fallen by about 50 basis points over that period. This matters because the level of bond yields across the curve is even more important than the level of the federal funds rate for determining the overall impact of monetary policy on the economy.

Bond yields hardly moved on today’s decision, evincing the Fed’s desire to not upend current market expectations.

Still, this raises a question: Why did markets and the Fed shift so drastically toward thinking more aggressive rate cuts were appropriate? In the past few months, we’ve seen mild inflation data continue to roll in. Powell noted that overall PCE inflation was likely to be 2.2% year over year for August, almost in line with the Fed’s 2% target. Meanwhile, the labor market has become more concerning, with unemployment rising by over 0.5 percentage points in the past 12 months and nonfarm payroll employment growth decelerating. Economic activity is still expanding at a healthy pace according to the gross domestic product data, although anecdotal data from the “Beige Book” survey is more concerning.

PCE Price Index vs. Core PCE Price Index

Altogether, Powell noted that the “risks to achieving employment and inflation goals are in balance,” after high inflation being the overwhelming concern over the past two to three years. To elaborate, that means that ongoing concerns about bringing inflation back to the Fed’s 2% target (which would call for restrictively high interest rates) are equally balanced by concerns that the economy and labor market could slip into a recession (which would call for low interest rates). With those two factors in balance, that calls for a federal funds rate much closer to its “neutral” level. The exact level of neutrality is uncertain, but it’s thought to be around 2%-3% according to Fed officials. Cutting by 50 basis points makes more sense when considering the large divergence between a 2%-3% neutral rate and the preexisting federal funds rate north of 5%.

We think the federal funds rate is likely to follow a course in line with today’s FOMC projections, at least through the end of 2025. This amount of monetary easing should be sufficient to keep the economy out of a recession. The uptick in unemployment is far from alarming in our view. With GDP still growing solidly, we find it hard to believe that the labor market is going to spontaneously lurch off a cliff. This should keep the Fed’s cutting to a more measured pace in future meetings.

The wait is over: The Fed cut rates for the first time in over four years.

The Federal Reserve announced on Wednesday that it will lower its benchmark interest rate to a target range between 4.75% and 5.00%, an aggressive half-point cut.

This was a major headline event, but not a surprise. The market knew this was coming and asset prices—stocks, bonds, and everything in between—had already adjusted accordingly. That’s how markets often operate, efficiently pricing in expected outcomes well before they occur.

This likely began in July, when small-cap stocks experienced their best single month of performance in two decades, driven by anticipation of the Fed’s plan to lower rates. Another notable example is the 30-year mortgage rate, which was 7% in July and has since dropped to 6.2%. The same trend is evident in the 10-year Treasury yield, which was at 4.4% in July and now hovers near 3.7%.

In short, the market had already done much of the Fed’s work for it. This is something to keep in mind as you ponder what may come next or work with clients to properly contextualize the situation.

On a recent episode of the Odd Lots podcast, Pimco Chief Investment Officer Dan Ivascyn discussed this topic and was blunt in his assessment of what it means, stating:

“If you have a three-to-five-year time horizon, this is really noise,” while adding, “It’s less important than people think it is.”

Of course, reasonable people can disagree. Stating the obvious: Rates going up versus rates going down is a completely different market environment. As Warren Buffett himself has said, interest rates act like gravity on asset prices, which is to say, this does matter.

Ivascyn further added that his executive team, along with former Fed Chairman Ben Bernanke—now a Pimco advisor—sits in a conference room during Fed press conferences, analyzing subtle changes in tone and language. Any notable developments could influence how they trade and position their portfolios.

But for financial advisors discussing this topic with clients, the most important question might be: What do rate cuts tell us about the future? The answer: For those with a time horizon beyond a few years, it’s often just noise.

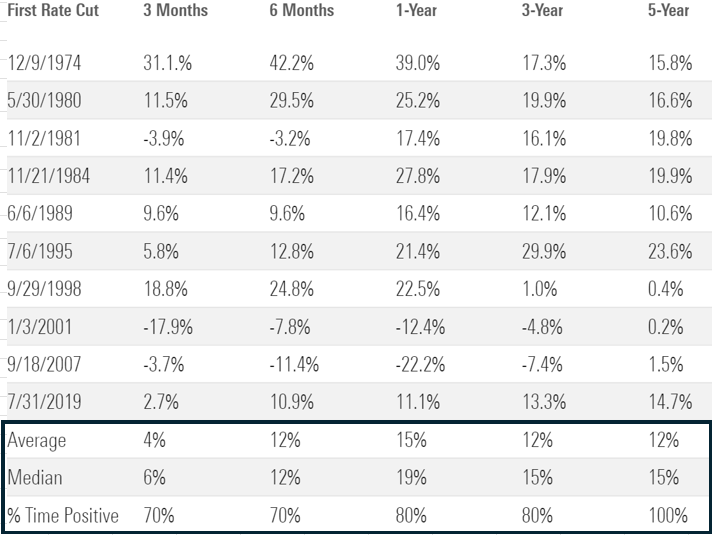

Data from Ned Davis Research shows that, historically, stocks performed well in the 12 months following the first rate cut. Since 1974, stocks have been positive 80% of the time, with an average return of 15%.

Stocks & Rate Cuts (S&P 500 Forward Returns Post Rate Cut)

However, investing can always be a funny game of caveats or “well, actually.” This might come in the form of, “Well, actually, the returns are much worse if a recession hits.”

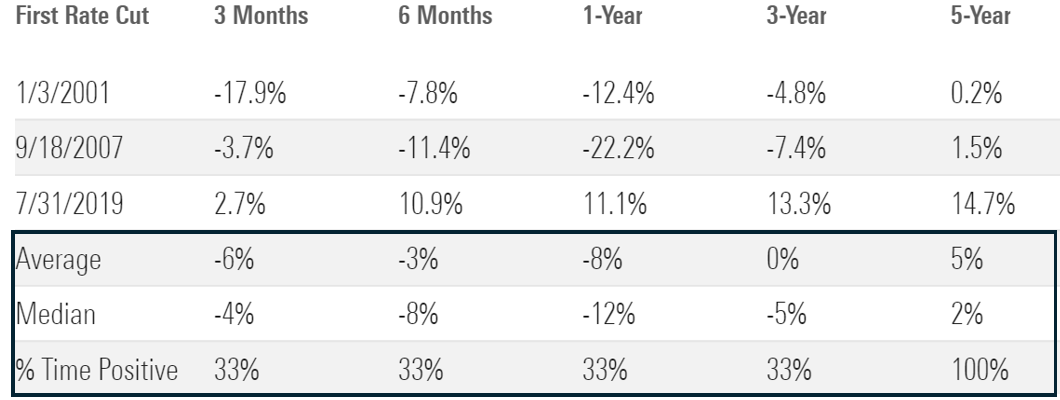

This is true; however, the sample size is much smaller. In the event of a recession, returns one year later are positive only 33% of the time, with an average return of negative 8%.

Stocks, Rate Cuts, & Recessions (S&P 500 Forward Returns Post Rate Cut + Recession)

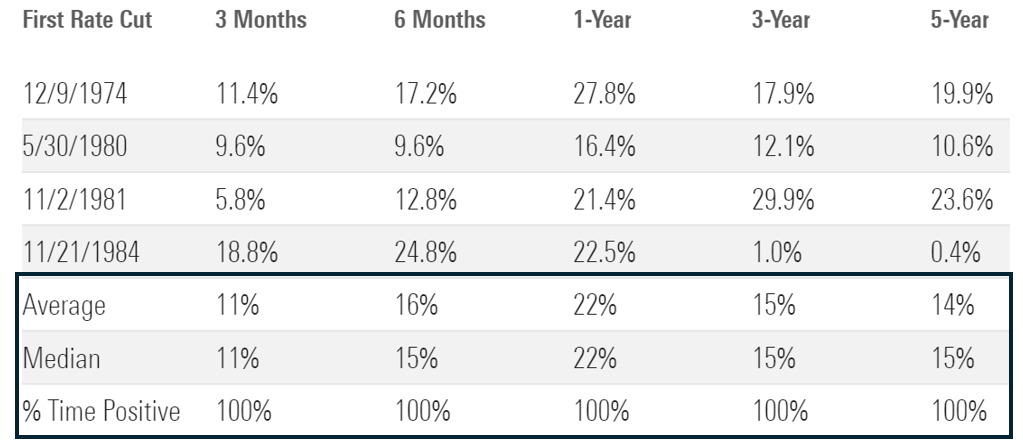

But if you flip that analysis, focusing only on periods where the Fed cuts rates without a recession, the results change dramatically. Stocks are positive in every period, with an average return of 22% one year later.

Stocks, Rate Cuts, & No Recession (S&P 500 Forward Returns Post Rate Cut + No Recession)

Which scenario is more likely—recession or no recession—remains open for debate. Depending on your view, you can find compelling data to support either scenario.

Anecdotally, the financial strain on lower-income consumers is becoming evident, which could foreshadow more economic cracks. Companies like Dollar General and Ally Financial, which serve the most cost-sensitive consumers, have highlighted these concerns.

There’s also the impact of how aggressive the Fed was with its first rate cut, opting for a 50-basis-point cut instead of the usual cadence of 25-basis points during the hiking cycle. Perceptions matter, and this may give many the impression that the Fed is concerned about the economy.

On the other hand, the world’s largest and most profitable companies are investing at the highest levels in recorded history, driven by expected productivity gains from artificial intelligence and other innovations. This surge in investment from the world’s most successful companies seems inconsistent with a recession.

While you can attempt to split the proverbial atom over which economic scenario is more likely, a simpler approach rooted in a basic investing truth is this: Extending your investing time horizon increases your probability of success.