The recent tragic death of UnitedHealthcare CEO Brian Thompson has cast a spotlight on the often-overlooked connection between corporate greed and healthcare access. As a former insider in the industry, I have firsthand knowledge of the tactics used to prioritize profits over patient care.

For decades, the healthcare insurance industry has successfully shielded itself from public scrutiny and reform efforts. By investing heavily in lobbying, campaign contributions, deceptive PR campaigns, and even charitable donations, they've cultivated an image of benevolence while simultaneously restricting access to essential care. This strategy has enriched executives and shareholders at the expense of patients' health and well-being.

The focus on shareholder value over patient care is evident in the annual investor days hosted by these companies. These events, attended by high-powered investors and analysts, prioritize profit margins and share prices over the needs of patients. The word "patient" is rarely, if ever, mentioned, while discussions revolve around strategies to maximize profits and control healthcare costs.

One such strategy is the widespread adoption of high-deductible health plans (HDHPs). These plans force patients to shoulder significant financial burdens before their insurance coverage kicks in, often leading to delayed or denied care. This approach, while financially beneficial for insurers, can have devastating consequences for patients, particularly those with chronic illnesses or unexpected medical emergencies.

The recent rise of corporate consolidation in the healthcare industry has further exacerbated the problem. By acquiring physician practices, clinics, and pharmacy benefit managers, insurance companies can vertically integrate their operations and control the entire healthcare delivery process. This allows them to maximize profits by reducing reimbursements to providers and limiting patient access to care.

The tragic death of Brian Thompson serves as a stark reminder of the human cost of corporate greed. It is time for a fundamental shift in our healthcare system, one that prioritizes patient care over profits. We must demand transparency, accountability, and ethical behavior from the healthcare insurance industry. By exposing the tactics used to deceive the public and undermine patient care, we can pave the way for a more equitable and compassionate healthcare system.

Public Reactions to Luigi Mangione's Arrest Highlight Deep-Seated Resentment Towards Health Insurers

The arrest of 26-year-old Luigi Mangione for the murder of UnitedHealthcare CEO Brian Thompson has sparked a range of public reactions, from schadenfreude to outright giddiness. The McDonald’s in Altoona, Pennsylvania, where the tip leading to Mangione’s arrest allegedly originated, has been inundated with angry reviews. Meanwhile, “Free Luigi Mangione” merchandise is selling rapidly on Amazon, and supporters have offered to fund his defense. A sign reading “deny, defend, depose”—a message found on bullet casings at the murder scene, referencing the insurer's claims denial strategy—is prominently displayed above a Baltimore highway. Even non-leftist podcaster Joe Rogan has expressed sympathy for the anti-insurer sentiment, calling the health insurance business "fucking gross."

Rogan’s sentiment resonates with many. The emergence of Mangione as a folk antihero underscores the deep societal revulsion towards the American healthcare financing system and the suffering it causes.

Private health insurers are a significant part of the problem in the healthcare sector. The reliance on private health insurance leaves millions uninsured and underinsured, with nearly half of working-age adults skipping care due to cost. Insurers' inability or unwillingness to negotiate provider prices leads to inflated costs, and the administrative burden of the system eats up over a trillion dollars annually. The Congressional Budget Office found that a single-payer system could cut these costs by $528 billion while covering tens of millions more people.

The public's resentment is not just about abstract critiques but about how these issues affect their lives. Administrative bloat leads to countless disputes over necessary surgeries and prescription costs. Claim denials are common, with UnitedHealthcare rejecting 32 percent of claims. Surveys show that around 20 percent of insured people face claim denials annually, and nearly half experience issues with their insurance.

From a patient's perspective, the reasoning behind these denials can feel inscrutable. Health insurers force individuals to navigate complex administrative processes, often without compensation. In a country with many problematic industries, health insurers stand out for the indignity they impose on users who require essential healthcare services.

Until recently, insurance companies rarely faced consequences for their actions. They continue to profit, rewarding CEOs with massive salaries while patients suffer. This zero-sum game pits patients against insurers, with the latter profiting from making healthcare worse for those who need it.

The public gains nothing from this misery. The resources and energy spent on maintaining health insurance could be better used elsewhere. Eliminating private insurance and implementing a system like Medicare for All could provide universal, continuous coverage more efficiently and with less hassle. Other countries have successfully implemented such systems.

While murder is never justified, the public anger is understandable. Politicians like Bernie Sanders, Elizabeth Warren, and Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez have acknowledged this anger and the need for change. The next step is to channel this anger into building a new, more equitable healthcare system.

Relative health expenditures in low, lower-middle, and upper-middle-income countries are almost entirely composed of government schemes, which do not require financial contributions from beneficiaries and out-of-pocket spending. The 2024 Global Spending on Health report by the World Health Organization (WHO) from December 9 shows that 43 percent of all health spending was out of pocket in low-income countries in 2022, compared to 19 percent in high-income countries. The potential result is worse-quality healthcare and a lack of access to necessary medical procedures in times of macroeconomic crises.

Social health insurance and nonprofit schemes are also responsible for significant spending shares in upper-middle and high-income as well as low and lower-middle-income countries, respectively. Social health insurance is a contributory healthcare scheme implemented in many European countries like Germany or France. In the former country, for example, one-half of the cost of mandatory health insurance is deducted from an employee's salary, and the other is covered by the employer.

Voluntary private health insurance, on the other hand, makes up only a minority of the overall health spending, reaching an eight percent share in upper-middle-income countries. Countries are grouped according to World Bank group definitions updated in 2023, with the upper-middle income group composed of nations like Montenegro, Belarus, Namibia, Turkey, or Peru that have a gross national income per capita between $4,516 and $14,005.

Overall, estimated health expenditures worldwide stood at $9.8 trillion in 2022, more than doubling compared to figures from 2000. Domestic public spending, which according to the WHO report is "health expenditure funded by domestic sources, including general taxation, nontax revenue, and social health insurance contribution", made up $6.1 trillion or 62 percent of the total. The United States alone was responsible for 43 percent of global health spending, with all other high-income countries like Japan, France, Germany or the United Kingdom contributing an additional 36 percent. Overall spending of low and lower-middle-income countries only makes up around three percent of the global health expenditure.

According to the Global Health Expenditure Database by the World Health Organization (WHO), the global average out-of-pocket expenses related to health across 192 countries made up 30 percent of all health expenditures per capita in 2022. This type of spending includes over-the-counter medicine, health aids, or, as is the case for the U.S. healthcare system, deductibles or co-pays. While most high and upper-middle-income countries have a lower share of out-of-pocket spending due to nonprofit schemes, government transfers, and comprehensive social health insurance, this type of spending makes up two-thirds or more of all health spending in thirteen countries and territories.

Among this group are Turkmenistan, Armenia, Afghanistan, and Nigeria, each exhibiting an out-of-pocket spending share of more than 75 percent. The United States, which is the only advanced economy with no robust universal health coverage, has a share of eleven percent. Looking at absolute instead of relative numbers, overall out-of-pocket spending grew to $471 billion or around $1,400 per capita according to the NHE fact sheet published by the Centers for Medicaid & Medicare Services. Private health insurance spending in the United States constituted 29 percent of national health expenditure, amounting to $1.3 trillion.

A comparison between the United States and other leading economies reveals that the U.S. has the same relative level of out-of-pocket spending as Germany and Japan as well as two percent less than the United Kingdom and two percent more than France. China, the second-biggest economy after the United States, exhibits an out-of-pocket spending share of 34 percent, despite almost universal healthcare coverage. This is likely due to a lower level of benefits, necessitating covering larger health expenses with personal money.

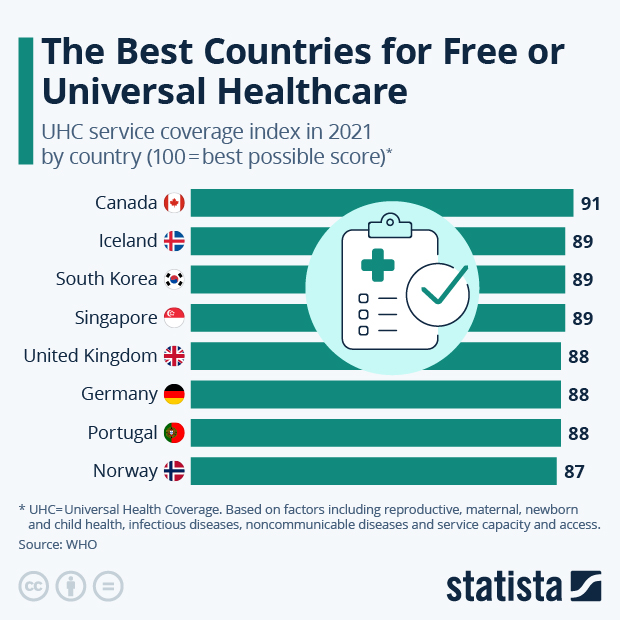

Canada is the leading country worldwide for essential healthcare coverage, according to The World Health Organization’s (WHO) World Health Statistics 2024 report. The organization ranked 194 countries based on a selection of indicators of key health concerns such as reproductive, maternal, newborn, and child health, infectious diseases, noncommunicable diseases,s and service capacity and access.

The WHO is monitoring universal health coverage by tracking two main indicators worldwide: the coverage of essential health services (SDG 3.8.1) and the lack of financial protection (SDG 3.8.2), which is defined as the “proportion of a country’s population with large household expenditures on health relative to their total household expenditure.”

This is to support the UN's aim of achieving universal health coverage by 2030, which includes financial risk protection, access to quality essential healthcare services, and access to safe, effective, quality, and affordable essential medicines and vaccines. As the WHO explains, this is because "protecting people from the financial consequences of paying for health services out of their own pockets reduces the risk that people will be pushed into poverty because the cost of needed services and treatments requires them to use up their life savings, sell assets, or borrow – destroying their futures and often those of their children."

While this chart only reflects the coverage element of UHC, it still serves to highlight the extent to which global inequalities exist in terms of that access. Where Canada received a total score of 91 index points out of 100, followed by Iceland, the Republic of Korea, and Singapore, each with 89 points, this is a stark contrast to countries at the other end of the spectrum such as South Sudan (34), Central African Republic (32), Papua New Guinea (30), Chad (29) and Somalia (27).

It’s also important to note here that since this data focuses on a nationwide level, it hides regional inequalities within countries and communities. For example, according to the WHO, coverage of reproductive, maternal, child, and adolescent health services tends to be higher among those who are richer, more educated, and living in urban areas, especially in low-income countries, while people living in poorer households, rural areas and in households with older family members are more likely to be further pushed into poverty by out-of-pocket health spending.

In terms of tracking overall global trends, WHO researchers outline how improvements to health services coverage have stagnated since 2015, rising only three index points to 68 by 2019 and remaining there until 2021. This is the equivalent of about 4.5 billion people living without full coverage of essential health services in 2021. Meanwhile, in 2019, out-of-pocket health spending pushed 344 million people further into extreme poverty and 1.3 billion into relative poverty.

December 12 marks the UN's International Universal Health Coverage Day.

.webp)